Jason Burke, The Guardian writes: In the days following the killing of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011, there was a surge of interest in the family of the al-Qaida founder and leader. One son had been shot dead during the raid on the high-walled house in the northern garrison town of Abbottabad, while confused reports described at least a dozen children or grandchildren, and between two and four wives, left stunned and bloodied by the US special forces when they left.

But the story moved on. Three years later, al-Qaida was pushed into the shadows by a breakaway faction, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Isis). The centre of gravity of Islamic militancy seemed to have shifted decisively to the Levant. The family of bin Laden were forgotten.

The narrative reaches from Pakistan to Mauritania, where a key informant of the authors now lives, and starts days before the 11 September attacks on the east coast of the US in 2001. It ends last year.

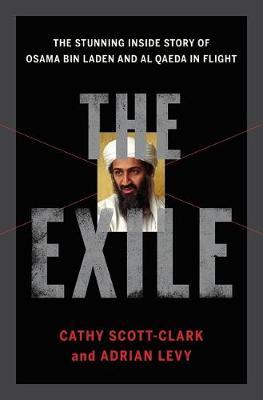

The book fills in many important gaps in our knowledge of al-Qaida.

A detailed account of the group’s internal dynamic demonstrates once more that the threat came not from a faceless international organisation composed of thousands of fanatical followers “brainwashed” into obedience, but from a relatively small band of committed men of disparate backgrounds and views whose shared objectives did little to limit fierce arguments over strategy. Most senior al-Qaida figures, The Exile shows, opposed the 9/11 attacks, or knew nothing about the plan. In 2002, a key senior militant called Saif al-Adel, now number two in the group, launched vitriolic attacks on Bin Laden whose campaign of violence, al-Adel believed, was completely out of control.

It is, however, the account of the life of the Bin Laden clan, painstakingly reassembled through dozens of no doubt lengthy interviews with family members, that remains The Exile’s most impressive achievement. The book follows those relatives and associates who remained with, or were able to join, Bin Laden in Pakistan after the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, and describes in appalling detail their claustrophobic life in Abbottabad as the US agencies closed in.

But it also follows the fate of those members of the clan, and a large number of senior veterans of the group and their families, who fled to Iran. Their fate there was effectively determined by a power battle between Iranian hardliners, who wanted to use these al-Qaida assets as weapons in their constant effort to weaken the west and extend their own influence in the region, and reformists, particularly many elected civilian officials. The latter even considered handing over their “guests” to the US in a bid to improve relations.

But when the US rejected Iran’s offers of a new relationship in 2002, the hardliners took control of their detention. For more than a decade, these “guests”, all connected to the world’s pre-eminent Sunni Islamic extremist group, remained in the capital of the world’s leading Shia Muslim power, under the control of Iran’s most ideologically committed faction, the Quds force. Analysts have long known that some al-Qaida militants and their families stayed in Iran between 2002 and recent years, but the account in The Exile is the only authoritative description of their time there.

Understanding this apparently esoteric episode is important today. The key figure overseeing the detention of the al-Qaida families in Iran was General Qasem Soleimani, the architect of Iran’s military efforts in Syria and Iraq. In the summer of 2015, five senior members of al-Qaida, including al-Adel, travelled from Iran to Syria via Turkey. Their release was part of the broader bid by Iran to roll back the influence of the west and its local allies in the Levant.

If the rigid structure of The Exile occasionally gives the impression of reading an expanded timeline, and the language sometimes lurches into airport thriller-ese, this does little to detract from a gripping inside account of the recent history of a terrorist group and a family that remains a potent threat.

Hamza bin Laden, one of Osama’s most cherished sons, appears to be taking on a role as the new face of al-Qaida. Now in his late 20s, Hamza has issued a series of audio messages. The latest 10-minute tape, in mid-May, called on followers of al-Qaida to attack Jews and westerners wherever they find them, using any means available.