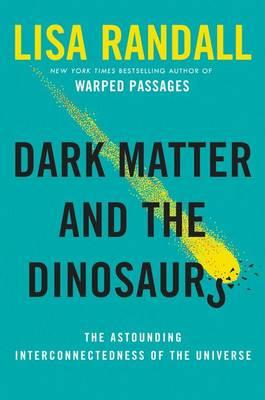

The ever brilliant Maria Popova writes in her newsletter Brainpickings: Every successful technology of thought, be it science or philosophy, is a time machine — it peers into the past in order to disassemble the building blocks of how we got to the present, then reassembles them into a sensemaking mechanism for where the future might take us. That’s what Harvard particle physicist and cosmologist Lisa Randall accomplishes in Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the Universe (public library), which I recently reviewed for The New York Times — an intellectually thrilling exploration of how the universe evolved, what made our very existence possible, and how dark matter illuminates our planet’s relationship to its cosmic environment across past, present, and future. Randall starts with a fascinating speculative theory, linking dark matter to the extinction of the dinosaurs — an event that took place in the outermost reaches of the Solar System sixty-six million years ago catalyzed an earthly catastrophe without which we wouldn’t have come to exist. What makes her theory so striking is that it contrasts the most invisible aspects of the universe with the most dramatic events of our world while linking the two in a causal dance, reminding us just how limited our perception of reality really is — we are, after all, sensorial creatures blinded by our inability to detect the myriad complex and fascinating processes that play out behind the doors of perception.

Randall weaves together a number of different disciplines — cosmology, particle physics, evolutionary biology, environmental science, geology, and even social science — to tell a larger story of the universe, our galaxy, and the Solar System. In one of several perceptive social analogies, she likens dark matter — which comprises 85% of matter in the universe, interacts with gravity, but, unlike the ordinary matter we can see and touch, doesn’t interact with light — to the invisible but instrumental factions of human society:

Popova concludes: Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs is a wonderfully stimulating read in its entirety. Although Randall points out that there are “no shortcuts to scientific knowledge,” she covers an impressive amount of material and connects a vast constellation of dots with captivating clarity — a formidable feat of bridging our solipsistic and short-sighted human vantage point with the expansive 13.8-billion-year history of the universe.