By Mark Mordue

The sun gets buried behind afternoon cloud cover. I drive towards Westfield Bondi Junction in Sydney as a gloom drops from above upon the suburb and the day.

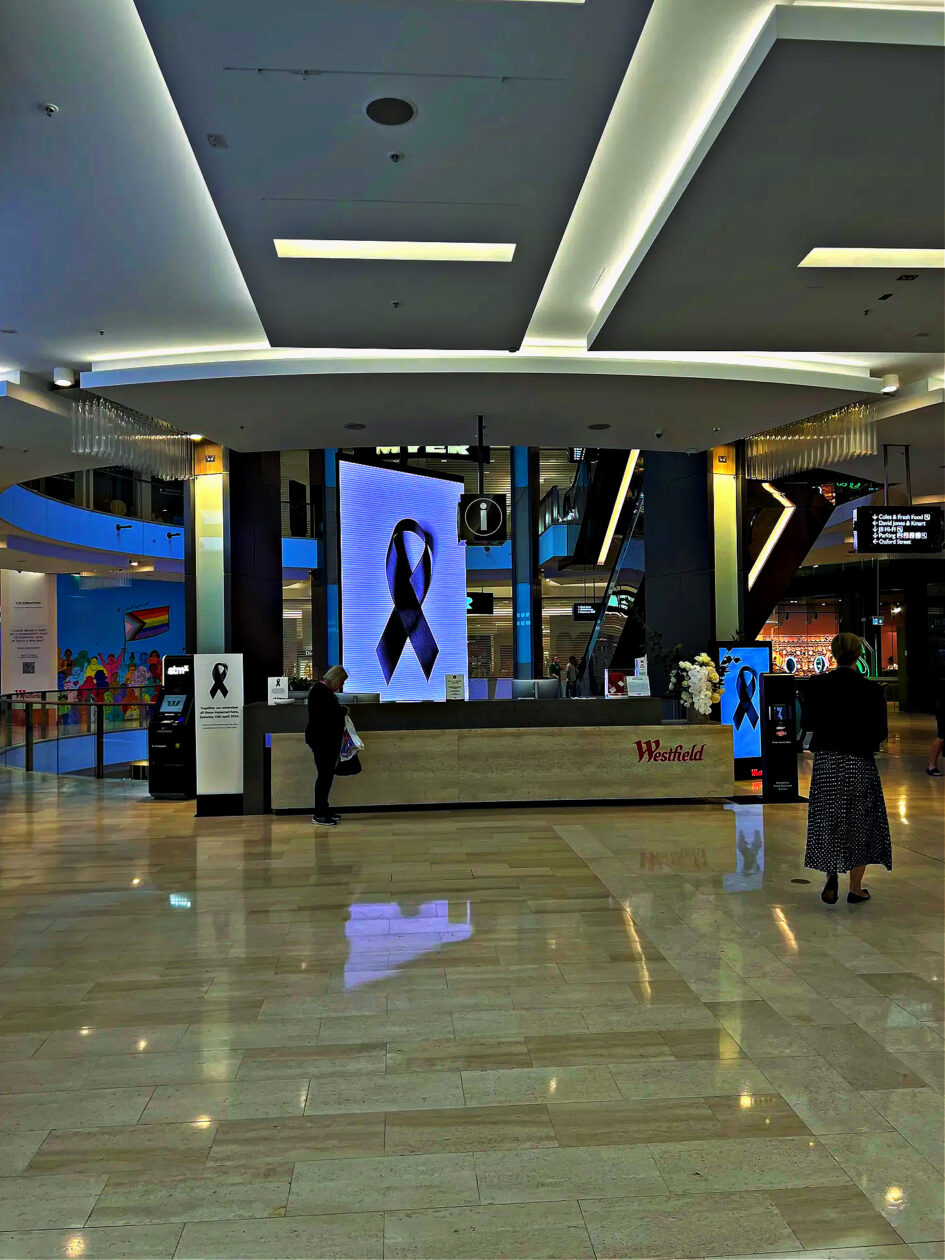

Inside the large shopping centre things are unusually muted, all its retail outlets closed for business. Large, lit images of black ribbons signal this is a place for shared grieving today, morphing the place into a kind of temporary church.

Less than a week has passed since six fatal stabbings occurred at Westfield Bondi Junction. Everything shines so sanitised and bright inside the building it only intensifies more ghostly, news-breaking afterimages, as if those who died and all the associated traumas have not yet left the building.

In my experience, Bondi Junction can be an odd and uneasy place in even the best of times. The privileged and their exclusive retails outlets rubbing up against less salubrious takeaways and discount chemists; dodgy characters with a mad look or desperate ‘cool’ sliding through the routine movements of business people and store employees.

Even today, as the afternoon slants into greyness and the suburb presents its most respectful face after a tragedy, a few characters emerge that make you feel both sad and wary as they cross a road. How do we cope with these lost and unwanted figures among us? Mostly by forgetting or avoiding them.

Six hospitals were put on high alert last Saturday after a lone male went on a rampage with a knife. Joel Cauchi, a schizophrenic who had been living between his car and a storage facility, was finally shot dead by a brave female police officer who had to face him down. After asking him to “drop it”, he’d come at her with a knife that looked about as large as short sword. A group of men who were backing up the police officer described Cauchi as having “black eyes”, “skinny”, “dirty”, “there was no one home”.

There were eighteen victims in all, doctors and nurses fighting to save life and limb across the weekend. Of the wounded, no one knows how it will affect their lives in the longer run. Five women and one man were killed, their life stories defined in media profiles via their last social media posts. And with such notes, a terrible sense of rupture rather than rapture taking them away from this world… Ashlee Good, 38; Dawn Singleton, 25; Jade Young, 47; Pikria Darchia, 55; Yixuan Cheng, 27; and Faraz Tahir, 35.

Many others shared in the horror: shopkeepers pulling down metal grills and protecting customers inside their stores; a man with nothing more than a bollard in his hands, fending off the killer on an escalator; pained and noble figures like the two shattered men who were later grilled outside in a tv interview, pushed to talk about how they just tried to save a woman (Ashlee Good) who bled to death in their the hands while they also tried to staunch the stab wounds on her nine-month old baby.

People are still in hospital, the worst out of their ‘serious condition’ and now stable. Ashlee Good’s child one of the survivors.

On Level 4 of the Westfield Bondi Junction shopping centre in Bondi Junction, white wreaths are being laid down all day Thursday. There’s long line of people; some have bouquets obscured by beautiful black wrapping paper from a local florist, the flowers so perfect and startlingly fresh it’s a pain all its own.

A separate crowd forms itself into a half-moon away from those lining up, lingering before where all the wreaths and flowers form into an altar inside the shopping centre for those killed. As individuals, couples and family groups take their turn, people kneel, bless themselves, or bow their heads.

A few books are left open on a table to write condolences. There’s repeated emphases in these messages on ‘never forgetting you’, ‘sorry’, ‘our hearts are with you’, ‘love’, ‘heaven’, ‘bless you’… some of the messages are quite long, half a page or more of impassioned sympathy, less notes than agonised and consoling love letters.

Small black ribbons are handed out, pinned to t shirts, lapels, dresses. A sign where the wreaths gather (mostly snow-white and flushed with the most delicate hints of yellow) says to all who are present: “We come together to remember the lives of those who lost their lives here, Saturday 13 April 2024.”

A bearded, senior-looking police officer chats to a chaplain with a name card on his chest. ‘Brian’ holds his hands folded reverently in front of him. An older women leads a young Gothic girl away , the teenager sobbing, inconsolable. Tears of this kind are hard to be so close to. Her trembling body shaking all who feel her passing by.

Mothers who look too young to be mothers wheel their prams forward, their babies looking upwards curiously into the shopping centre lights.

Along with the intermittent squeak of the elevator, there’s that deep murmuring echo you always get when voices rebound against the surfaces of any shopping mall. Even so, the place takes a whole new intensity with the grieving crowd. There’s a conscious quietness to how people talk to one another, when they talk at all.

The police officer takes off his cap to reveal a yarmulke. Two female members of the Red Cross walk along the line and through the crowd that continues to linger as if the place itself has an answer for them. The Red Cross women have been handing out a few small teddy bears. A few children hold on to their tiny gift. An older woman, standing on her own beside the chaplain, grips her somewhat childish gift to her chest as if it is easing or protecting something inside her.

Around all of them, the closed retail outlets remain a dominating presence, fashion stores and brand signage looming. It’s a difficult atmosphere in which to find the sacred, a place where the grief feels like it might easily be consumed and forgotten or, perhaps worse, fetishised and commodified.

As a journalist I am hardly unaware of my own potential complicities today. It has certainly not taken much to see the awful events seized on and stained by voices happy to co-opt people’s lost lives into Islamophobic and anti-Semitic smears. Every prejudice and theory under the sun pushed along by ‘toxic masculinity’ op-ed thinkers, mental illness reductionists and others online.

A little less ‘knowing’, a little more sensitivity feels necessary. Real lives lost in narrative fragments… the loving mother protecting her baby to the last from the stabbing attack; the bright young woman with a comms job at a fashion house; the female Bronte life saver and community figure; the artist and designer who could speak three languages; the Chinese university student enjoying her studies in Sydney; the Pakistani Muslim refugee who’d fled persecution in his own country and was working his first Saturday shift as a security guard.

In Toowoomba, Queensland, the awful early interviews with the parents of the killer. A mother letting us know he was a loved son, not abused, “top of his class”, a normal boy “until he got sick” at age 17. The father, voice breaking, apologising and acknowledging the futility of his apologies for his son’s acts. “He was such a tortured soul… tortured and frustrated.”

For a while I stand back watching everyone inside Westfield Bondi Junction, then I cross the floor and strike up a conversation with the chaplain. He keeps those hands of his calmly folded in front of him; the Red Cross women nod towards him as they do another circuit. The chaplain tells me their teddy bears are “just little symbols of hope. They say we are not giving in to hate, to anger, to darkness.”

For him, the most impressive thing here has been “the silence. How quiet people are. Even the children. A shopping centre like this is usually much more crowded, busy, people rushing around, maybe even being a bit angry or irritable as they move about. But you can feel something very different today. The quietness,” he says again, “and the respect. This place is like the heart of a village when you think about it. People come here to meet one another, to relax and have a coffee, to buy clothes or gifts for themselves or their loved ones.” He stops and thinks a moment. “The quietness reminds people how close we really are. How connected.”

More and more people file in. I make my way downstairs to leave. As I near the entrance, I see the older woman who I met briefly upstairs with the chaplain, still holding her teddy bear. She waves to me like I am an old friend who knows her – then calls out, “I might go see Brian again,” pointing back up to where the wreaths of white are being laid. “He’s a nice chaplain.”

I’m a bit confused as to why this is so important I need to know. Then I realise she is concerned for me and sharing how she is coping in case I might need a little help too. “Yeah,” I say back to her, my voice coming out louder than I mean it to sound across the shiny marble floor. “He’s a good guy.”

Outside it’s become quite cool, specks of rain beginning. There’s an odd shiver in the air, not quite tears-in-spirit, but something akin to elemental tears nonetheless. Then the sky cracks open completely and the rain comes down with lightning flashing and frighteningly close thunder. People stand under shopfront awnings for shelter, the pouring rain and sharply chilled air transforming the street into something oddly subdued as people are forced to stop and wait, a great cathedral for all who stand watching the world above them.

It’s as if the church-like feeling inside the shopping centre has expanded its mood across the entire suburb, married itself to the sky. There is this feeling of heaven talking to us, too, of course; of some parting communications being made from above.

For those who see it that way, rain-shaped tears explode into stars on the road, washing down in rivers off the buildings. Then the downpour just stops. With a sudden, strange burst of sunlight and warmth again, the road glowing so bright it is difficult to keep your eyes open and see where the light upon it might lead us.