By Douglass S. Rovinsky, Alistair Evans and Justine W. Adams, Monash University

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, is an Aussie icon. It was the largest historical marsupial predator and a powerful example of human-caused extinction. And despite being extinct since 1936, it still gets featured in popular media.

Yet much is still unknown about the thylacine, as its extinction left us with almost no direct observational data. Several mysteries remain regarding its specific ecology, including the question of how wolf-like it was.

In a new study published in BMC Ecology & Evolution, my colleagues and I tackle this question. We show the thylacine was indeed similar to canids, a family which includes dogs, wolves and foxes.

But more specifically, it was similar to those canids which evolved to hunt small animals — as opposed to the wolf (Canis lupus) or wild dog/dingo (Canis lupus dingo), which are large-prey specialists.

Moulded by our environments

When European colonisers first saw the thylacine, they noted its wolf-like appearance and judged it based on that assumption: like the wolf, it would pose a threat to their livestock.

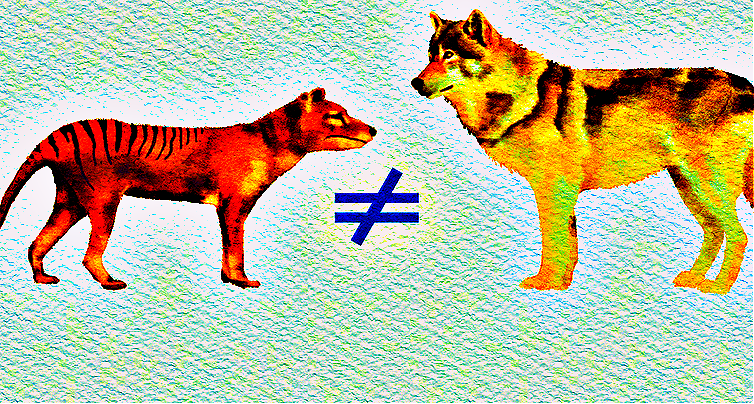

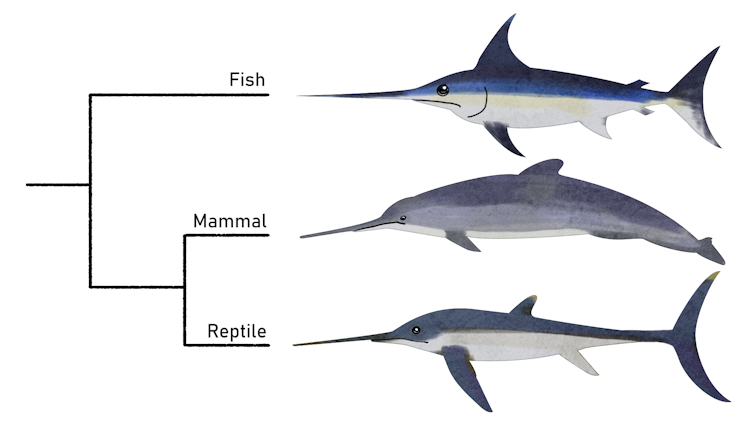

This superficially wolf-like appearance has been taken to mean the thylacine is a textbook example of convergent evolution: where two unrelated animals evolve similar traits in response to similar pressures. The similarities are so striking it’s even sometimes called the “marsupial wolf”.

Studying convergent evolution is a promising way for scientists to infer the behaviour and ecology of extinct animals that can’t be directly observed. Ecology is the study of how species interact with their physical surroundings. So, if an extinct animal shares a similar shape with one living today, we can assume they probably filled a similar ecological niche.

Since the thylacine’s ecology is uncertain, comparisons with comparable species are one of the only ways to understand it. And it’s wolf-like appearance at face value has led to the thylacine and its ecology being assumed similar to that of the grey wolf and its closest relatives, such as the dingo.

But what if that was wrong?

Getting into the right headspace

We decided to put this assumption of ecological similarity to the test. To do so we needed a wide range of ecologically meaningful animals to compare with the thylacine. After all, even though the thylacine was a marsupial (like a koala) it’s fair to say it wasn’t hanging out in trees munching on eucalyptus!

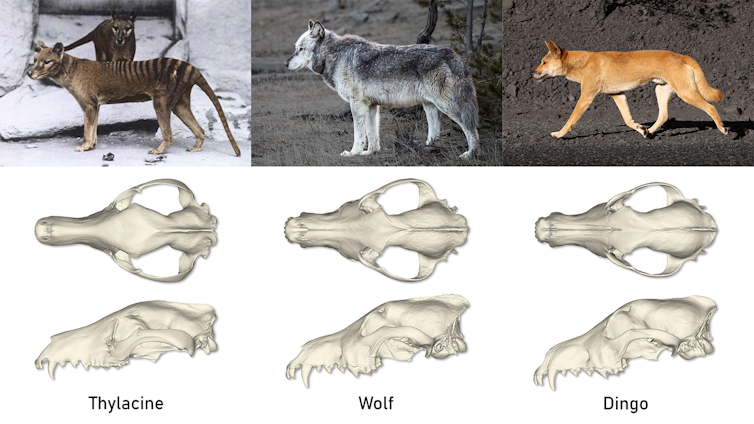

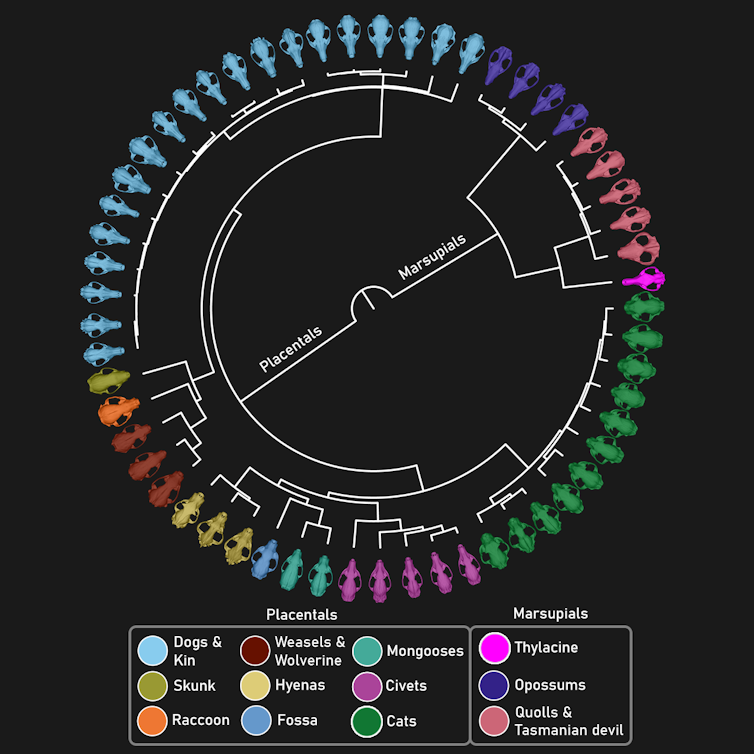

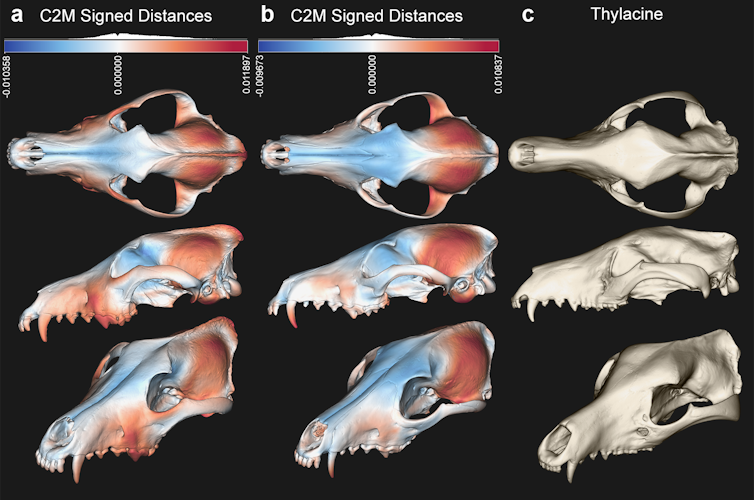

Using hand-held 3D scanners, we scanned hundreds of skulls from 56 different species of carnivorous mammals, with specimens obtained from more than a dozen museums around the world. This enabled us to build a skull “shapespace” to then see where the thylacine would fit among the others.

We looked for evidence of convergent evolution by observing which of the other carnivorous mammals’ skulls were shaped most like the thylacine’s.

A case of mistaken identity

It turns out the skull shape of the thylacine is significantly convergent with that of some canids, but not with the usual suspects. We found no meaningful level of convergence with either the grey wolf or the dingo, and only a small degree with the red fox.

What we did find, however, was strong support for convergent evolution between the skulls of the thylacine and another rag-tag group of canids: African jackals and South American “foxes” (which aren’t actually foxes). Ecologically, these canids are vastly different from the wolf and dingo. Also, unlike the wolf, they specialise in hunting small prey.

This brings us back to one of the more powerful uses of studying convergent evolution: the ability to infer the ecology of an extinct animal. Since the thylacine’s skull shape was more similar to that of the African jackals and South American “foxes” than the wolf, it likely shared a similar ecological niche with the former.

Therefore, the thylacine probably also preferred hunting relatively small prey such as pademelons, bettongs, bandicoots and young wallabies.

Interestingly, however, one of the most striking findings was that the thylacine did not actually overlap with any of the other predators, canid or otherwise. While it was similar to some canids, it was not identical. This highlights that even our more precise analysis may paint the thylacine with too broad a brush.

Judged by appearance

The thylacine was hunted to extinction for its wolf-like appearance. This reaction, like most based on first glance, was devastatingly wrong. Although the thylacine turns out to not be very wolf-like, it’s still a wonderful example of convergent evolution.

Read more: Why did the Tasmanian tiger go extinct?

Then again, it truly was different enough from other carnivorous mammals that we still can’t say we precisely understand its ecological niche. When we lost the thylacine, we lost something truly unique for its time.

Our understanding of the thylacine is, even now, that of a faded and blurry snapshot. Perhaps, with more research in the coming years, we can make it a little more clear.

Douglass S Rovinsky, Associate research scientist, Monash University; Alistair Evans, Associate Professor, Monash University, and Justin W. Adams, Senior Lecturer, Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.