Sharolyn Anderson, University of South Australia

In a world increasingly illuminated by artificial light, the beautiful night skies of a small coastal town in South Australia have attracted international recognition. Carrickalinga on the Fleurieu Peninsula is Australia’s first official Dark Sky Community. The title rewards a dedicated community effort to combat light pollution and preserve the natural environment at night.

The journey began three years ago when I was a PhD candidate at the Australian National University, working on the value of night skies. I was a regular visitor to Carrickalinga, but this time conversations at a picnic one evening turned to the clarity and brilliance of the stars. I was inspired to work with the locals to nominate Carrickalinga as a “Dark Sky Place”.

My recent research suggests restoring dark skies would be worth US$3.4 trillion (A$5.16 trillion) to the world, annually. That’s largely because light pollution is disrupting nocturnal pollinators, altering predator-prey interactions, and changing the behaviours of nocturnal species.

Light pollution has detrimental effects on wildlife, human health, and ecosystem functions and services. But there are simple solutions. By embracing responsible lighting practices, everyone can contribute to a healthier future in which the wonders of the night sky are accessible to all.

Understanding light pollution

Light pollution refers to human alteration of outdoor light levels. Excessive or misdirected artificial light brightens the night sky, diminishing our ability to see stars.

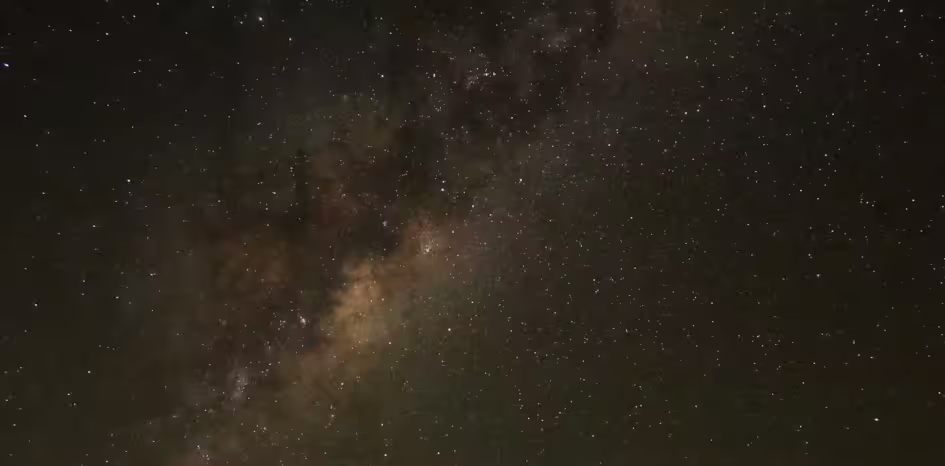

Research shows the problem is getting worse. Light pollution increased by 7–10% a year from 2011 to 2022. More than a third of people on Earth cannot see the Milky Way.

Light pollution not only affects our view of the cosmos, but also wastes energy and money, contributes to climate change and has significant repercussions for both ecological and human health.

Nocturnal animals such as bats and certain birds rely on darkness to navigate and find food. Insects, crucial for pollination and as a food source for other wildlife, are also affected. Artificial light at night is contributing to their decline.

In humans, studies have shown artificial light interferes with circadian rhythms, leading to sleep disorders and other health issues.

The global Dark Sky movement

DarkSky International, formerly known as the International Dark Sky Association, is a global network of volunteers combating light pollution. The non-profit organisation established in 1988 is based in Tuscon, Arizona in the United States. But more than 193,000 people across more than 70 countries are involved, including astronomers, environmental scientists and the public.

The International Dark Sky Places Program was born in 2001 when Flagstaff, Arizona was named the first International Dark Sky City. Now the program certifies five types of Dark Sky Places: sanctuaries, reserves, parks, communities, and urban night sky.

DarkSky says the aim is to “preserve and protect the nighttime environment and our heritage of dark skies through environmentally responsible outdoor lighting”. It recognises places that demonstrate a commitment to reducing light pollution through public education, policy, and promoting responsible lighting practices.

There are now well over 200 Dark Sky Places across the globe. This covers more than 160,000 square kilometres in 22 countries on six continents.

Australia’s Dark Sky Places

Australia is home to several Dark Sky Places, each recognised for their exceptional night skies and dedication to reducing light pollution. These include:

1. Warrumbungle National Park (2016) – Australia’s first Dark Sky Park, near Coonabarabran in west-central New South Wales.

2. The Jump-Up (2019) – Dark Sky Sanctuary in Winton, western Queensland

3. River Murray (2019) – Dark Sky Reserve, including parts of South Australia’s Riverland

4. Arkaroola Wilderness Sanctuary (2023) – Dark Sky Sanctuary, northern Flinders Ranges, South Australia

5. Carrickalinga (2024) – Australia’s first Dark Sky Community, Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia

6. Palm Beach Headland (2024) – Australia’s first Urban Night Sky Place, outer Sydney, New South Wales.

Our journey in Carrickalinga

Since 2021, the Carrickalinga community has worked tirelessly towards achieving International Dark Sky Community certification. The journey involved several key initiatives:

- Sky Quality Metering Program: regular measurements of sky brightness to monitor light pollution levels

- Community engagement: presentations to community groups and the district council to raise awareness about light pollution, information stalls at local markets, community consultation process (led by the District Council of Yankalilla)

- Educational materials: printed flyers, video, and a “Star Party” including a presentation on First Nations cosmology

- Policy development: collaboration with the district council to create a lighting policy including public lighting design that complies with both Australian standards and DarkSky requirements.

Carrickalinga is currently upgrading existing public lighting to reduce light pollution. This will involve a new lighting design plan that reduces correlated colour temperature, ensuring shielded downward-facing lights minimise skyglow, glare and light trespass.

Reducing light pollution by upgrading lighting fixtures does not compromise safety. Dark sky does not mean dark ground.

Light pollution has become such a problem because our lights are unnecessarily bright and poorly designed. Fixing the problem simply involves changing the colour from white to amber, shielding and targeting lights so they do not shine upwards and outwards, and reducing wattage where it is surplus to requirements for people’s safety.

How you can help

Achieving and maintaining dark sky status is not difficult but it does require ongoing community effort. Here are the five principles for responsible outdoor lighting, which apply equally to domestic as well as public lighting:

- Useful – use light only if it is needed and has a clear purpose

- Targeted – direct light so it falls only where it is needed

- Low light levels – light should be no brighter than necessary

- Controlled – use light only when it is needed

- Warm colours – use warm coloured lights wherever possible and avoid short-wavelength (blue–violet) light.

An inspirational journey

Achieving International Dark Sky Community status was a significant achievement in preserving the natural night environment and educating the local community about light pollution. This accomplishment demonstrates the power of community action and serves as a model for others.

By protecting our night skies, we safeguard a vital part of our natural and cultural heritage and also promote healthier ecosystems and communities. Carrickalinga’s journey serves as an inspiring example of what can be achieved through collective effort and dedication to preserving our planet’s natural beauty.

I would like to acknowledge the enormous contribution of Carrickalinga Dark Sky Community volunteer Sheryn Pitman, who works for Green Adelaide in the South Australian Department for Environment and Water, and helped write this article.

Sharolyn Anderson, Research scientist and Adjunct Associate Professor, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.