As told to his son Mark Slaski

The Battle of Monte Cassino was a pivotal battle in the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943–1944.

Monte Cassino was a mountain top monastery, transformed by the Germans into a fortress. It formed a crucial part of Hitler’s line of defence protecting the heavily fortified town of Piedimonte, and ultimately the route to German occupied Rome. The allied forces had been trying to break through this line for the past nine months and had taken heavy losses.

The battle for the monastery at Monte Cassino is well documented — many men from many nations lost their lives in an effort to take this strategic position. Eventually on May 18th 1944 the mountain was taken. This is the story of one man’s journey from deportation in Poland to battle in the mountains of Italy. I tell it not because it is unique but because it is a story shared by tens of thousands of Poles, and because it remains largely untold.

For me it had been a long and hard journey from my native Poland and some of the hardest years of my youth, as I grew from schoolboy to soldier along the way.

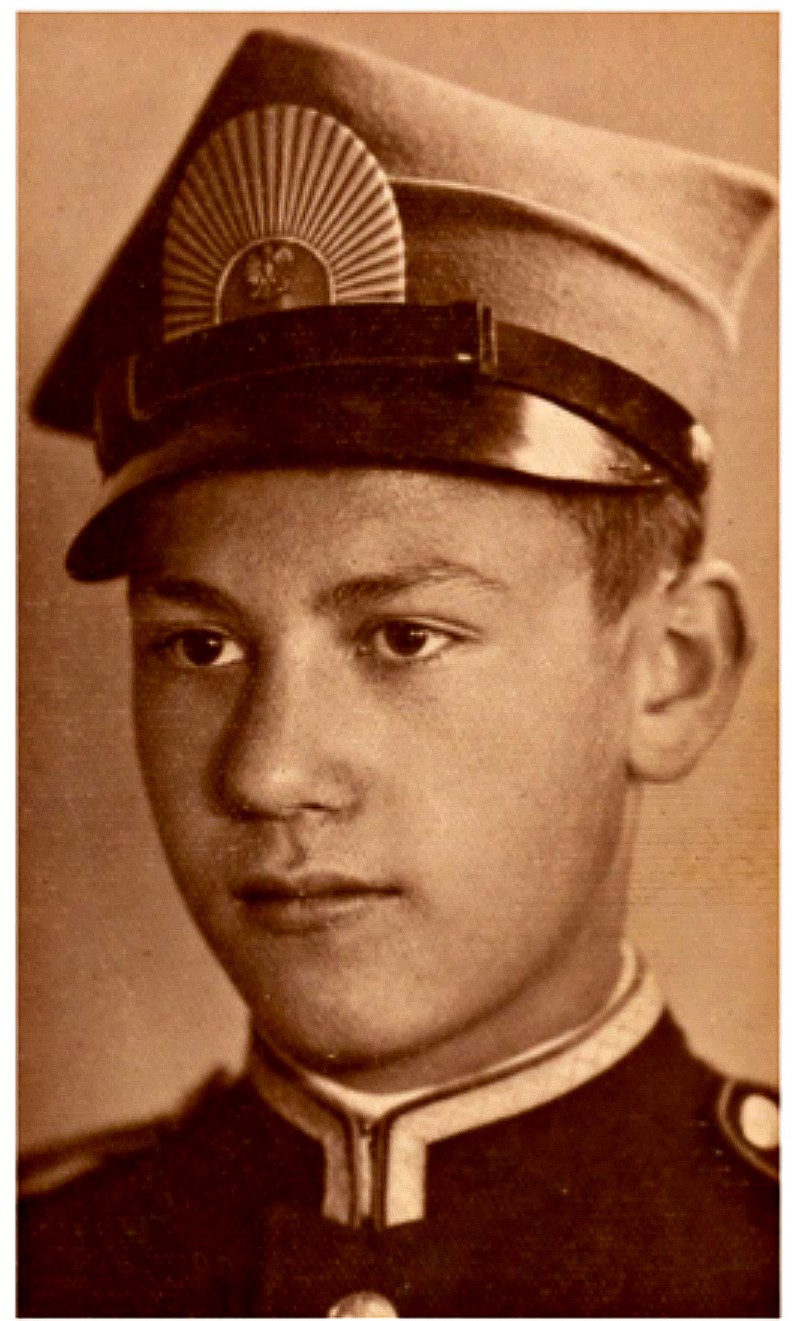

When war broke out with the German invasion of Poland on September 1st 1939, I was 16 years old and, with my younger brother, attending the prestigious Korpus Kadetow, boarding school in Lwow in eastern Poland — considered to be one of the best schools in the country, full of tradition with a military background. My father was a major in the Polish army.

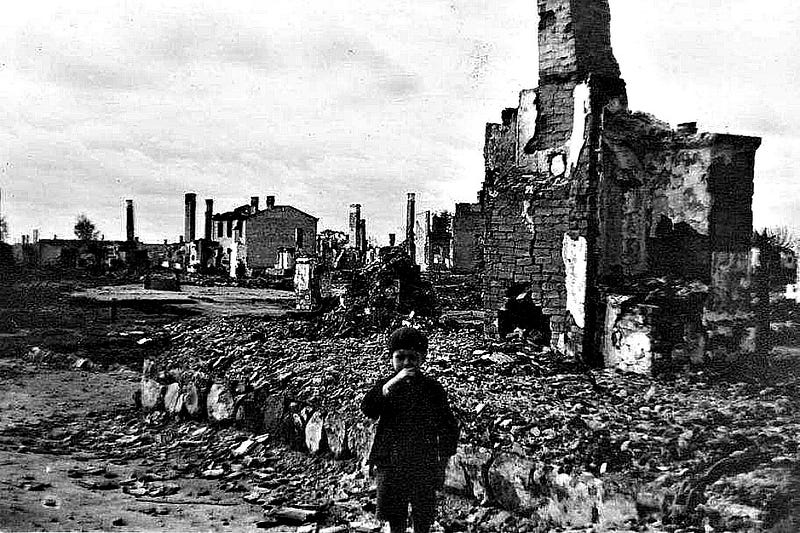

The German advance through Poland was rapid. Within a few days, and with no warning, the city of Lwow was bombed, resulting in a considerable number of civilian casualties. For a time Peter and I stayed at school and performed guard duties around the area.

Within a few weeks the invading German army moved closer and closer, pushing back the remnants of the Polish army towards Lwow. Finally, with the German army less than 100 miles away, the school was evacuated and we stayed with my mother at my grandmother’s house.

By the middle of September any organised resistance by the Polish army had fallen away. Accounts of the Polish cavalry equipped only with sabres attacking the Nazi invaders are stark confirmation of the unpreparedness of the Polish army and the outdated thinking of the High Command. Sometime that month my father arrived and my parents decided to move us all further east to evade capture by the Germans. We travelled in my father’s mobile field office, a specially converted bus.

The plan was to travel north-east to the town of Kostopol 150 miles away where my parents had some friends. Unfortunately on our arrival we learned that Soviet forces, taking advantage of the German invasion, had themselves attacked Poland from the east to capture the Polish eastern provinces. We were now trapped between the advancing Russian and German armies, the Polish army was in disarray and the country was about to fall.

My father located some retreating Polish infantry units and left to join them and mount some sort of resistance.

It was the last time we ever saw him

The Beginning of the Worst of Times

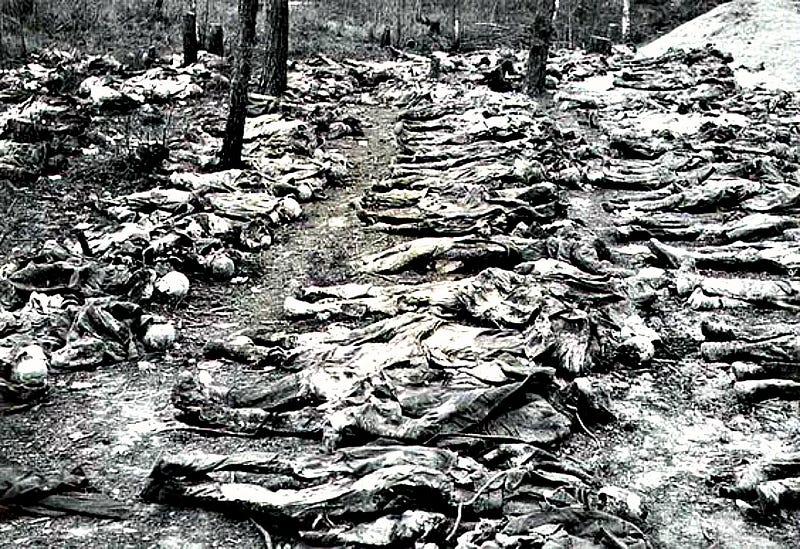

After several days Kostopol was overrun by hordes of Russian soldiers and my father was taken prisoner. We discovered much later that my father had been taken to Kozielsk and in April 1940, together with over 14,000 other Polish officers, he was murdered and buried in the a mass graves of the Katyn forest massacre. Shot by the NKVD secret police on the orders of Stalin.

Late in October 1939 my mother, brother and I managed to return to our grandmother in Lwow, now occupied by Russian soldiers. Mother decided to return to our house back in Warsaw, now occupied by the German army. Her plan was to salvage anything she could from our home and return to Lwow; we only had our summer clothes with us and the winter was fast approaching. Tragically her journey across the newly created frontline separating the invaders took much longer than she anticipated.

When she finally returned to Lwow it was only to find that my grandmother, brother and I had been arrested and deported to Siberia two days earlier. My brother and I did not learn the fate of our mother or father until after the war was over.

My grandmother, brother and I were arrested on April 13th 1940. Together with many others who shared our destiny, we were deported to Siberia. It is difficult to give an accurate figure, but I believe the number of deported Poles was in the region of three and a half million people.

The whole process was familiar to us as for months the citizens of Lwow had suffered the same fate. The hammering at the door always came in the middle of the night. In the doorway we were confronted by a group of Russian soldiers and a civilian; a party official. They told us we were to be deported, and we were given one hour to pack any belongings, no destination was mentioned.

We were escorted with our luggage to a waiting lorry and taken to the nearby railway yard. Waiting there were long trains consisting of covered cattle trucks, specially converted for carrying large numbers of people. We were the first to arrive and ordered to board one of the trucks. Very soon more and more deportees arrived and packed in until all the trucks were fully loaded. The train journey lasted more than two weeks and we were allowed off only a handfull of times to stretch our legs.

The train crossed the Ural Mountains and after travelling for several more days eventually came to a halt. We were ordered to unload and only then were we told we were in Kazakhstan, in a town called Kostanay. Awaiting the train were several lorries, enough to load the occupants of each cattle- truck onto a separate lorry. The lorries then took-off in various directions, ours travelled some 30 miles or so, to a collective farm, or kolchoz’ in the village of Kirovka.

This was to be the final destination of our long 2,000 mile journey.

Kirovka

Each family was directed to their future ‘home’, ours a two-roomed mud-hut, already occupied by a Russian family, one room for us and one for them. No time for questions or any objections, this was to be our home from now on. We were given a few days to become accustomed to the local conditions and were then gathered together and directed to our various jobs.

Myself and Janusz, a young man of 20 also from Lvov, were allocated to the Tractor Brigade. Our job was to help the team of 20 or so tractor drivers.

To my surprise, the drivers were all young women aged between 18 and 22 years old. The work was hard, the farm fields were huge; five miles long by five miles wide, each field taking over a week to plough. We worked in two 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, with occasionally a day off for rest. Whilst the women drove the tractors, we young helpers had to follow behind making sure the ploughs were operating properly and not clogging up.

When not working we slept in small huts stuck out in the middle of the vast expanse of fields. Work continued day and night, it was the time of sowing the grain and the fields had to be prepared.

From the beginning Janusz and I talked of escape. Our plan was to somehow return to Poland, cross the border to Hungary, at that time a neutral country, and eventually get to France. We hoped ultimately to join a new Polish army. Though we had no news whatsoever of events in Europe, we assumed that the war was continuing and wanted desperately to be a part of it, and help defeat our country’s enemies.

After only a few weeks an opportunity came our way, I remember it was the May 22nd, and Janusz and I had a day free of work. Together with Janusz’s mother, a lady in her early forties, we seized the opportunity and left the village, our excuse that we had to collect some fuel from the steppe.

Overcome by my desire to escape and fight for Poland I did not tell my brother or grandmother of our plan. In retrospect being the oldest I should have stayed to look after them, something I regret to this day.

Janusz and I had hoarded some food, and our plan was to walk to the railway station at Kostanay some 30 miles away, jump a train, and travel as far west as possible, heading home to Poland. Unfortunately when we arrived at the station we had missed the train by a few hours and the next train was not due for three or four days.

It was too dangerous to stay in Kostanay so we had no choice but to walk the railway tracks to the town of Troick some 180 miles further north. There we hoped to connect with the Trans-Siberian Line and continue our journey west.

We walked at night and during the day we hid in the steppe to sleep. I should explain the Russian steppe is a vast area of wilderness; flat grasslands with the occasional tree. After a few days we had finished our meager rations, the rest of the journey we had to live off the land. One day we saw some people planting potatoes, after they left for the day we dug up some of their crop and baked them on a fire. Our only supply of water was from the pools left after the rain, which we filtered through a handkerchief.

It took us a week to reach the station at Troick, and once there we found a suitable hiding place from where we could observe the movement of the trains. Eventually we located what we thought was a suitable train and, under the cover of darkness, we sneaked into a truck with a cargo of very fine coal. We dug ourselves in up to our necks and waited for the train to start its journey. We travelled in this way for several days, from time to time the train stopped and we would sneak off in search of food.

Eventually we reached the industrial town of Orsk, where the coal was to be delivered to the local foundry. It was time to change our transport.

Our Luck Ran Out

Carefully we left our hiding place in the coal truck and crept onto another train travelling west. This time our shelter was a refrigeration truck. We hid there and waited for the train to move. Suddenly the truck doors were noisily thrown open, and moments later we were surrounded by heavily armed railway police.

This time our luck ran out, we had been spotted boarding the train. I am not sure who was more frightened, ourselves or the police, because when we were discovered the three of us were black from head to toe; covered in coal-dust.

We were taken to the office of the station-master, an NKVD officer, and after a preliminary interrogation put on a train returning east, our escape was over. We were on this train for several days guarded by a Russian soldier, probably going home on leave. Eventually we arrived back again in Kostanay. Our expectation was that we would be sent back to the kolkhoz but instead we were taken straight to the NKVD prison. It was now June 6th 1940, we had been on the run for 15 days and travelled over 550 miles.

Thus began a new chapter of my life; only a month short of my 17th birthday I was separated from Janusz and his mother and locked in a small cell all alone.

I was interrogated at different times both day and night. My accomplices and I had agreed our story in case we were captured. I kept repeating that on the kolchoz we had to work for a year before being paid, and that we couldn’t last that long, so we were trying to reach the industrial areas of Ukraine in search of work. My interrogators however were not interested in my stories, it was all a charade and it was clear that eventually my destiny was the labour camp.

After several days of incarceration and interrogation I became ill; I had a problem with my feet and could barely walk, no doubt as a result of our long trek through the steppe.

The Gulags

Nearly four months passed since our capture in Orsk, and at the end of September I was officially informed of my crime. I was charged with “the armed group escape from a place of deportation” (paragraph.82, part 2. of the Soviet Criminal Code of RSFSR).

There was no trial and I was sentenced to a ten-year term of imprisonment in a corrective labour camp, otherwise known in popular language as the gulag. Although the sentence was ten years all prisoners were aware that there was little chance of release and ultimately it was a life sentence.

They were in no hurry and I was transferred through several different prisons on the journey north to Siberia.

On my arrival at one of them I was put into a cell with about 50 others, but within a few hours the cell was packed with more than 200 prisoners.

There was not enough room for everyone to sit on the floor, so recent arrivals had no choice but to stand. After a few hours those sitting changed places and allowed those that had been standing a chance to rest.

My cellmates were people from all corners of the Soviet Union.

My eyes were opened to the differences in ethnic and cultural background, and in appearance, language, education, and religion. There were some older men, fluent in several languages, who before the revolution had been university graduates. Knowing hardly any Russian I was able to converse with some of them in German.

Many of the inmates were experts in their professions, such as engineers and accountants. There were also many uneducated ordinary men who had once earned a living with their hands. No matter what your background there was a distinct ‘pecking order’ in the prison, this was decided by such factors as type of crime; length of sentence; previous experience of the gulag.

Conditions in prison were harsh; food consisted of two bowls of weak, thin soup and a small piece of bread a day. Our clothes were rags, and there was a constant battle with lice and other infestations. Locked in our cell for 231⁄2 hours each day with just 30 minutes to walk around the yard, we passed the time with stories and an occasional game of chess.

I listened and learned a lot and when eventually my name was called for transfer to the gulag, I felt much better prepared for the life I was to face. It was now late October 1940 and together with a large group of prisoners I was once again taken to the station. We travelled in covered cattle-trucks, some 80 people in each.

After several days we arrived at our new destination, the Ivdel labour camp in the north-east Ural, near the Arctic Circle. In fact the gulag was really a collection of camps housing all together as many as 40,000 prisoners. The main camp was situated some distance from the train station, such as it was. So for our first night we were marched to yet another transit camp a few miles away.

Northern Ural in October is frozen and covered with snow; the temperature was around -20oc. In such conditions any type of work in the open is sheer hell. My first job was loading tree-trunks onto trains. Almost without exception the trains arrived at night. Prisoners were ordered out of barracks into the open, marched to the railway and we loaded the trains until the early hours of the morning.

After the loaded train departed we were allowed a very short rest before continuing to stack logs in readiness for the arrival of the next train. The ‘day shift’ usually continued for the next 14 hours and was often followed by another night of loading. It is hard to fully describe the physical exhaustion and devastating cold and the effects on a man already so dehumanised.

The first job when working out in the open was to start a fire in an attempt to stave off the cold. The trick was never to get too close to the fire; if the snow melted and your clothes became wet, frostbite and hypothermia could be minutes away. In practise no prisoner was allowed to stand long enough to gain any real relief from the flames.

One night, after the loading work had been completed, and the guards were counting the prisoners for the march back to camp, they realised I was missing. After a search they found me, I must have fallen asleep literally on my feet, because I was found collapsed and fast asleep on top of one of the smouldering fires. Thankfully I was found quickly, too much longer and I probably would have burned to death.

I continued this work through the winter, then I got lucky — I got frostbite.

Survival

My hands and feet were badly affected, and I was ordered to return to the main camp for treatment. I don’t think I would have survived work in the forest much longer. In spite of my injured feet I was marched the dozen or so miles to the medical centre in the main camp. My treatment there proved to be rather crude though effective.

After frostbite had been confirmed two heavy and strong men actually sat on me whilst a third man, calling himself a doctor, cut away the infected skin and flesh with a pair of scissors. There was no anaesthetic; he literally cut right down to the raw unaffected flesh. To my amazement this proved to be a success, and there was never a trace of the dreaded gangrene.

The most important fact was that I did not have to work for a month. Of course, in such cases, a prisoner goes on to the minimum food ration, barely sufficient to keep one alive. Not having anything to do and feeling hungry I gravitated towards the camp kitchen in search of food. If I was lucky I may get some work that might result in extra porridge.

As it happened luck was with me. During my travels and various incarcerations I had met a fellow prisoner whom I befriended by the name of Kandieev. To my surprise and joy Kandieev was now working in the kitchen; better still he was the chief cook. Such a contact could save a man’s life. Kandieev gave me a job cleaning the large kettles used for cooking the prisoner’s food.

Usually the best and most wholesome part of the soup was stuck to the bottom of the kettle. From time to time I was allowed to peel potatoes, and occasionally I managed to steal and eat one. This was the only means of getting the valuable vitamins needed to prevent scurvy.

I was beginning to learn that surviving the gulag was as much about who you know as what you know.

It was also obvious that prisoners who worked in the camp fared much better than those in the forest.

Political prisoners such as me rarely got ‘in-camp’ jobs; these were reserved for other types of offenders. In order to secure work inside the camp I was going to need connections.

My chance came when I was working in the kitchen and was able to do a favour for the man in charge; the canteen supervisor. The canteen supervisor had a girlfriend, her name was Tamara, and her job was to wash the canteen oor. The supervisor had other ideas for Tamara, so whilst they busied themselves each afternoon in the office behind the kitchen, for a few extra rations I kept look out and washed the floor. To this day I thank God for Tamara.

I was still on the sick list, but this would end before too long, very soon I would be back to work outside the camp. Prisoners would do anything to get out of working in the freezing forest. One day, during a visit to the pitiful medical centre for a change of dressing, I met a fellow prisoner who simply could not take the conditions any longer. In an attempt to escape forest work he had chopped off his own finger. His plan worked, he was put on the sick list, but unfortunately he also added five years to his sentence for the sabotage.

Hell on Earth

Prisoners died daily and they would be buried in shallow graves outside the camp fences, the frost too hard to dig for more than a few inches down. At night the blue foxes, whose fur was so prized across the cities of Europe, would come and dig up the corpses to take an easy meal. In the bright moonlight the glowing white stumps of bones rose from the ground like fields of flowers, a sight I would never forget.

Eventually I was sent back to work in the forest, but by that time the temperature had increased considerably, the snow started to melt as did the ice on the river. Nature wakes early and quickly in Siberia, she has only half the time than her sister in more moderate climates to perform all the miracles of growing, flowering, and bearing fruit. By the middle of September this has to be complete, otherwise winter steps in and kills everything. In the Spring the air is clear and the views, especially across the Taiga River, could be very beautiful.

Life in the camp however remained hellish. Hardly any of the prisoners ever tried to escape; there was simply nowhere to escape to. The only way out would be by rail and the guard dogs saw to it that nobody ever managed that. There was a story that the local tribesman, who lived in the forest, were offered a reward if they caught any escaping prisoners. Apparently the deal was they would get five roubles for returning a prisoner alive, and ten roubles for his head! True or false, this story, coupled with the fact it was sheer madness to escape to the vastness of the forest with inadequate clothing and little food, meant that escape never entered my mind. As far as I was concerned I was a prisoner for life.

Our poor diet meant that scurvy was a real problem amongst the prisoners. In order to get enough vitamins I would eat berries whilst out in the forest. However, this was all to no avail as eventually I was diagnosed with scurvy and once again found myself in hospital. This was a horrible time, many men died around me. There was little food and prisoners did what they could to scavenge any scraps and hide them. There were often fights as they wrestled each other for morsels of bread hidden about the person of a recently deceased prisoner.

As with my previous hospitalisation I volunteered to help in repairing the walls of the hospital hut and was allowed to remain in camp for a little while longer. However, there was another winter fast approaching and I knew this one would prove more difficult than the last. Most of my kitchen friends had been transferred to another camp, and I knew I would end up working in the forest sooner or later.

For the first time I started to believe there was no hope, and then the miracle happened.

In the camp we had no information of what was happening in the rest of the world. We knew nothing of the progress of the war.

In the summer of 1941, a new contingent of Polish prisoners arrived with the news that Germany had attacked Russia. Hitler had broken his pact with Stalin and the fragile peace between these two nations was over. This news was incredible and rumours spread that the Russians would now become our allies and that prisoners would be freed to fight alongside the Soviets. We hardly dare believe that we might soon be released, and tension in the camp grew daily.

Amazingly within the month all the speculation proved to be correct. Suddenly hard work in the forest stopped for all Poles. We were told we would be released and instructed to wait for our documents.

I Could Hardly Believe It

I could hardly believe it. Yesterday I was sure my destiny was to die in that gulag, and the next day life had changed again, soon I would be a free man. Waiting for documents was a frustrating time, but it was absolutely crucial to wait, a person could not move in Soviet Russia without the right documents.

The camp administration office was chaotic; as prisoners had arrived at camp their records were simply dumped on top of a large pile. This meant that the records of prisoners who, like me, were the first to arrive were at the bottom of the pile. Those who had been there the longest were dealt with last. Everyday that passed I feared the worst; something would go wrong, things would change again, and I would never be released. When I finally received my papers there were only five Poles left in the camp.

With papers in hand I was moved to my final transit camp, here I had to wait for several weeks before my final release. Amazingly, the first person I saw in the new camp was the kitchen girl Tamara, this time with a different boyfriend. Again, it meant an extra bowl of soup for me, and as always I was very grateful. Eventually, 18 months following my arrest in Lvov, I was freed from the Ivdel gulag.

It was September 1941, I was 18 years old.

I had a clear plan, and that was to return to my grandmother and brother whom I left in Kirovka collective farm 16 months earlier. On release each of us was given a small amount of cash, and this I spent on a train ticket to take me as far as possible. In the end it took me several weeks to reach the main town of Kostanay almost 1,000 miles to the South.

Finally I arrived in Kostanay, and only a 30 mile hike separated me from my family. It was late afternoon and I was exhausted, so I decided to rest and complete my journey the following day.

As I was settling down in a haystack to sleep, a man and a woman driving a small horse drawn cart appeared on the road. The man had spotted me and immediately approached and asked for my documents and questioned me as to what I was doing and where I was going. As luck would have it he turned out to be the leader of the collective farm neighbouring Kirovka. Satisfied with my papers and explanation he offered me a lift. This was heaven-sent and together with two loaves of bread I arrived at the entrance to the farm later that evening.

I asked a passer-by where my family lived and was directed to a small mud house. I walked slowly toward it, I remember being apprehensive as I did not know what I would find.

On nearing the house I passed a young man on the road and I realised that it was my brother Peter.

I called him by his name and he turned to face me not realising who I was — by this time I was swollen with hunger, had a long, dirty and shaggy beard and was dressed entirely in rags, even bundles not shoes or boots on my feet.

Eventually it dawned on him that this tramp was actually his brother. His shock was total; I don’t think he ever expected to see me again. He told me later that I was unrecognisable from the boy he had last seen a year and a half before; it had only been my voice that was in any way familiar.

In an empty room of the tiny mud house we stood looking at each other, unable to utter a word, contemplating the miracle of our reunion.

The Shock of Coming Home

I recall my brother was upset because he wanted to welcome me properly with some food, but the only food in the house was the bread that I had brought with me.

Such was the way of life in this hell on earth, a day to day fight for food and survival, hunger a permanent companion.

Soon after my grandmother appeared, crying at the door. She had been visiting some fellow Poles in a nearby village and they had given her the head of a cabbage; somehow she had lost it on her way home, and this was to be their meal for the day. In her upset she had not even noticed the stranger in her house.

News of my return spread to Kostanay, reaching the recently established Polish Mission. The Mission worked with the thousands of prisoners, deportees and refugees. One of their duties was to recruit Poles and help process them into the army.

A fully armed infantry division had already been formed and was undergoing training in a former Russian artillery camp in Tockoje.

Another division was being assembled and Peter and I received our call-up papers.

Like almost all other displaced Poles, Peter and I did not hesitate when called upon. Peter, who was only 16 years old, was too young to fight and had to lie and add a year to his age.

We liberated ourselves from the Kirovka farm and conveyed grandmother to the Polish Mission in Kostanay. More sad farewells and the brothers boarded the train for Troitsk, our first change on the way to joining-up in Tockoje, 600 miles to the west.

Eventually Peter and I arrived in Tockoje where our new Polish army had its headquarters. Our train was met by a number of Polish soldiers; it was wonderful to see again the White Eagle insignia worn on their caps and uniforms.

Our excitement turned to disappointment when we were told that our first destination was to be yet another transit camp, and that the number of arriving conscripts was so great that we would have to wait some time before being assigned a unit. As we resigned ourselves to more delays we heard a voice calling out “is there anyone here from Lvov?” Immediately we responded and to our joy we were taken to the headquarters of the newly formed 6th Recognisance Regiment of Lvov where we were offered a choice to join either the platoon of heavy machine guns, or the signal platoon. We opted for the signals.

We were issued our uniforms; Russian-type winter trousers and jackets and canvas jack- boots. The only other possessions were those we had brought with us, not much at all. Organisation was hampered by the surprising lack of officers reporting for duty. By late 1941 nearly 15,000 officers were unaccounted for. Attempts were made to track them down, but no trace could be found. We believed most of our officers had been imprisoned in Kozelsk, Starobelsk and Ostashkov, and we awaited their arrival. At that time we did not realise that the Russians had massacred thousands of those officers at Katyn in the early months of the war.

As a temporary solution to the problem an NCO school was formed and those with any military experience were sent for training to become ‘good corporals’. This also included Kadets like my brother and me. On arrival at the School we found that most of the other trainees were seasoned soldiers. Many already had war experience fighting the Russians in 1939, and they had since been imprisoned in prisoner of war camps.

Conditions in the camps were considerably better than those in the gulags, and as a consequence the soldiers were stronger and better equipped to deal with the harsh conditions. Training was supervised by one of the very few officers, a Lieutenant Sosnowski who had been an expert in training before the war. I was billeted in a tent with 17 other young men mostly from my old school. The training was physically tough and challenging, and the younger ones soon began to struggle. It was clear we were not ready to become corporals and we were returned to our units still as privates.

At the end of 1941 the whole of the 6th Infantry Division and the rest of the Polish Army, now nearing 70,000 solidiers, were moved out of Russia to Uzbekistan; a journey of nearly 1,500 miles and a week by train.

My unit was first stationed at Kitab and then Shahrizabs near the city of Samarkhand, not far from the border with Afghanistan. Shahrizabs was the summer palace of Genghis Khan 1261. I did not know this at the time, but the next two years were going to take me on a journey via the Middle East and North Africa to Italy. There would be many stops along the way.

The growing shortage of officers became chronic and it was decided to organise an officer’s training school. Much more to my liking I applied to join, and after passing an entrance exam, I was accepted. My brother was judged to be too young to apply.

There were nearly 300 men in officer training. I was put into the 2nd Company together with my school friends, the Kadets, who had also been in the NCO School. This time we decided to convince our superiors that we really were officer material. After three months of intense training most of us graduated in July 1942 with very good results; I graduated as 26th among 280 officer-kadets, and was promoted to Corporal kadet-officer. With this rank I was posted back to the1st Squadron, 6th Reconnaissance Regiment and placed in charge of a section of 12 men. My duties as a kadet-officer were the same as those of a 2nd Lieutenant, and I would eventually receive my commission two years later in 1944.

It was agreed to evacuate the Polish units to Persia, which was by now under British control. When we received our orders to move we departed from Shahrizabs without any regrets. Once again the whole regiment boarded a train for an eight day journey across the Karakum desert in Turkmenistan to Krasnovodzk on the Caspian Sea; from there we sailed for 3-days across to Pahlevi, in Iran. Our boat was the Kaganowicz; a cruise ship built for 1,000 passengers, now with more than 4,000 on board. For two weeks in March 1942 over 40,000 soldiers and civilians sailed this crossing in a grand exodus from Soviet oppression.

To safeguard the Middle East oil fields, the whole region was occupied by the allied armies. Russians controlled the north of Iran, the rest, including Pahlevi, by the British. Consequently, on disembarking in Pahlevi we came under British command, part of Central Mediterranean Force. It took a while to fully believe we were safely out of the hell that was Russia. As it happened we were probably the last transport out of the Russian zone. Within a few weeks they stopped any more Poles leaving. Many were trapped there for the duration of the war and far beyond.

We camped on the beaches of the Caspian Sea and after some weeks were again transported. We crossed the mountains of Iran until we reached north-eastern Iraq; a place called Khanaqin; here the temperature once again soared to 45 degrees centigrade and once more took its toll on our health. Due to the extreme heat, and exhausted from our experiences in Russia, all we could do was to rest; many men were hospitalized with malaria and other diseases. Some never recovered and spent the rest of the war in camps for the civilians, mostly in Africa. By early November 1942 we had again moved, this time to the town of Qizil Ribat.

Whatever winter there is in that part of the world had arrived and at last we had some respite from the killing heat.

By now the whole area was occupied by large numbers of troops. A new army was taking shape and getting organised; three infantry divisions, cavalry, artillery regiments, transport, reconnaissance and hospitals. A new armoured brigade was formed and we became the 6th Armoured Regiment of Lwow. Naturally all this involved a great deal of training. We had to learn everything virtually from scratch; tank driving, gunnery, radio communication, maintenance, all those things upon which ones life might depend in the future.

Originally we were given the old Valentine tanks, but in the spring 1943 the new Sherman tanks arrived. In the summer we moved to Kirkuk in Iraq and in the autumn we left for Palestine and reached what is now Gaza Strip. It was at this point that I met again Janusz (Kochanowski) my fellow escapee from the kolkhoz. He turned up in the same brigade and trained and later fought with us until losing a leg under mortar fire. As far as I know he survived the war and after emigrated to Canada. We finished our gunnery training in the desert around a place called Rafah and in January 1944 left for Egypt. We were positioned firstly near Tel-el-Kebir and then at Ikingi Mariut, 30 miles south of Alexandria.

At the end of 1941 Peter and I had joined a newly forming army in Tockoje; tens of thousands of men traumatised by their experiences in Russia, suffering untold health problems, poorly trained and with little or no equipment. Two and a half years and 5,000 miles later we were finally ready for the action we craved so much. At last we could be involved in fighting the enemy and taking back our country.

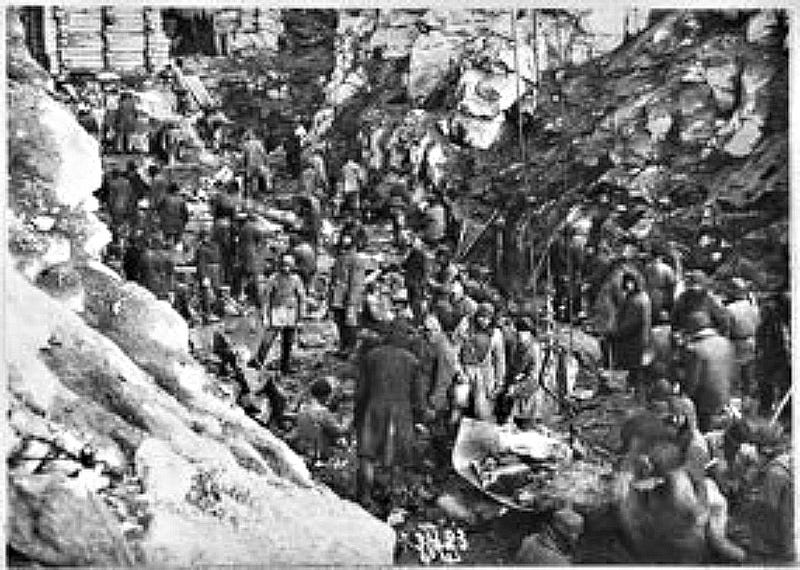

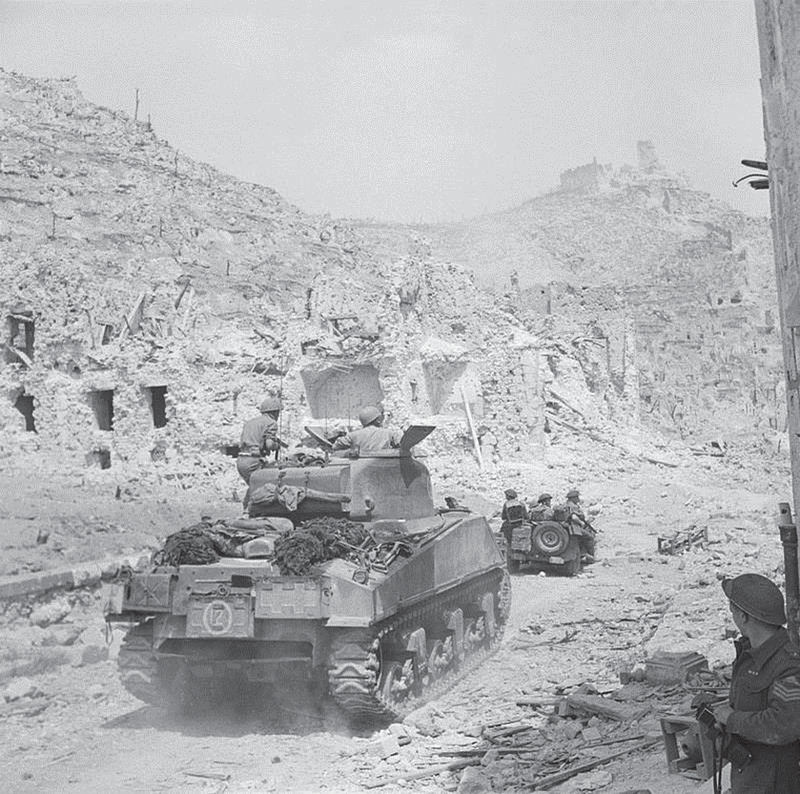

In March 1944 we left Egypt for Italy. Half the regiment were landed in Naples and the other half in Taranto. I was in the Naples group and we waited several weeks for the Taranto group to arrive. Ironically, being in Naples I was geographically nearer my home in Poland than I had been at any other time since my arrest in 1939. Our Italian campaign began with orders to journey north; our first encounter with the enemy was to be the battle for Monte Cassino and Piedimonte.

Tens of thousands of troops were killed there, especially Polish and Canadian troops, as General Anders later recounted:

Twenty two days under constant fire, in terrible conditions, seven days of fierce struggle to break German defences. It was not just the Battle of Cassino, it was a battle for Poland.

On 18 May at 9.45 am, a patrol of the 12th Podolski Lancers Regiment reached the ruins of the monastery at Monte Cassino, soon after that, the Polish flag was raised.

For many thousands of Poles Monte Cassino was the final resting place and the end of their incredible journey and fight for survival.

Millions Died Some Survived — We Survived

Following this victory, our regiment was given the specific objective of taking the town of Piedimonte; our personal baptism of blood and battle. The fighting was ferocious, my own regiment lost 78 officers and men, and the enemy hit 31 tanks; damaging them or destroying them completely. My own souvenir was a wound during the last day of action. My left cheek was cut either by shrapnel or a rifle bullet.

Some malicious people suggested that a face like mine did present an easy target, but there is no accounting for good and sincere friends!

For five days the Poles fought a seesaw battle with the Germans, taking positions only to be pushed back by fierce counter- attacks. The tide was eventually turned by our Polish armour; our crews managing to traverse the hills and rocky terrain to pound the German positions at close quarters.

On May 22nd the Germans surrendered and the town of Piedimonte was taken, the road to Aquino and further to Rome was opened. This proved a decisive and significant victory allowing the allies to advance on the capital.

After the victories at Monte Cassino and Piedimonte, we were allowed a short rest and in the middle of June we were moved east, to the Adriatic Coast. At this time I was promoted to platoon commander of 1st platoon; three tanks all to myself, I was very proud of this. In July 1944, the Regiment was again ordered into action, this time the target was the town and port of Ancona.

This was to prove a particularly difficult operation.

The battle for Ancona was to be led by the Lancers of the 15th Poznan Regiment. However, the day before the attack commenced we were told of the heavy German anti-tank defences guarding the town. These had to be destroyed before any serious assault could take place.

The task of clearing the defences was given to the 1st platoon of the 1st squadron of the 6th Armoured Regiment, my platoon! I realised, that my career as a commander could be very short lived, and this of all days was July 15th 1944, my 21st birthday. With the other tank commanders, Stachow and Wasiak, under my command, I decided that the best tactic was to move fast presenting a harder target. Stachow’s tank met a German tank pulling a large field gun; he fired and destroyed the gun with the first shot, unfortunately the tank escaped. Wasiak got behind a key enemy position and took some 30 prisoners. Later in the day his tank was damaged by a mine and threw a track.

There were many casualties and we lost among others our Squadron Commander when his tank was hit. With a final assault my tank eventually reached and held our agreed target and within the next three days the German resistance was broken and units of our 2nd Polish Corps entered Ancona.

After this action the Regiment rested in and around the town of Chiaravalle. Here we were visited by our then Prime Minister and Commander in Chief General Sosnkowski.

At this time I was also decorated with the ‘Virtuti Militari Vth Class’. It is awarded for “for exceptional bravery and courage, above and beyond the call of duty”.

It is the highest Polish military decoration, equivalent to the British Victoria Cross.

September came and with it more fighting. By now the momentum was with the allied forces and the German resistance was breaking. My Regiment was heavily involved on the river Metauro the Germans had their famous ‘Panther’ (Panzer) tanks. In one action I was very proud of hitting one tank and immobilizing another. Autumn came and with it the rains, making it almost impossible for the tanks to move. We were billeted first in the town of Sarsine on the Rubicon river, (Caesar Rubiconem transgresus dixit: Alea jacta est — the very same).

We crossed the Rubicon to a place called Poppi near Bibiena, where we were to spend the winter. At this time I was awarded yet another medal; the Cross of Valour (equivalent of the British Military Cross), and I finally got my promotion to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. This meant a rise in my pay and allowances most of it spent in the Officer’s Mess.

The Allied advance was gathering pace through Italy, the German Army was in retreat. Our Polish Forces were again reorganising and another Armoured Brigade was formed. More troops were being trained and I, now an experienced tank officer, was posted to the 15th Poznan Lancers as an instructor. The Brigade consisted of three cavalry regiments, initially equipped with armoured cars and about to receive Sherman tanks. I was posted to the Polish equivalent of a guards regiment and given command of the very platoon I had supported in the assault of Ancona.

It was hard to say farewell to my Regiment which had been my family for over 4 years, but orders are orders. My posting took me back to Egypt where I reported to my new Regiment, and started training fresh troops. The training lasted for 8 months, but as we came to the closing stages the news we had all been waiting for finally arrived.

On September 11th 1945, after six years of fighting, the German Army was at last defeated, and the war in Europe was finally declared over.

When victory was announced I was stationed in Alexandria. A boy of 16 when the war started I was now a young man of 22 years old. For all this time my focus had been on survival, now like many other Poles, the future was uncertain. Naturally we longed to return home and once again be with our families, but Poland had been ravaged by war and would never be the same again. I had no knowledge of the whereabouts of my parents and relatives or whether they had even survived.

Towards the end of the war I heard of some Polish schools that had opened in Italy. They were started for soldiers just like me; boys who before the war had passed matriculation and wanted to continue with further education.

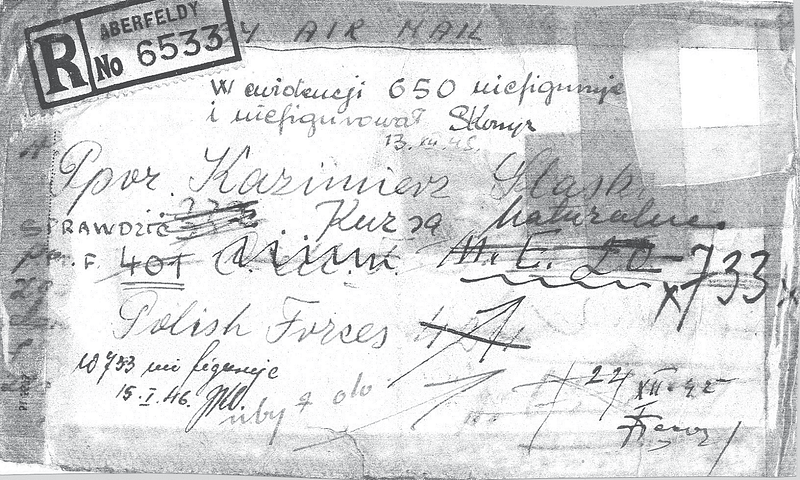

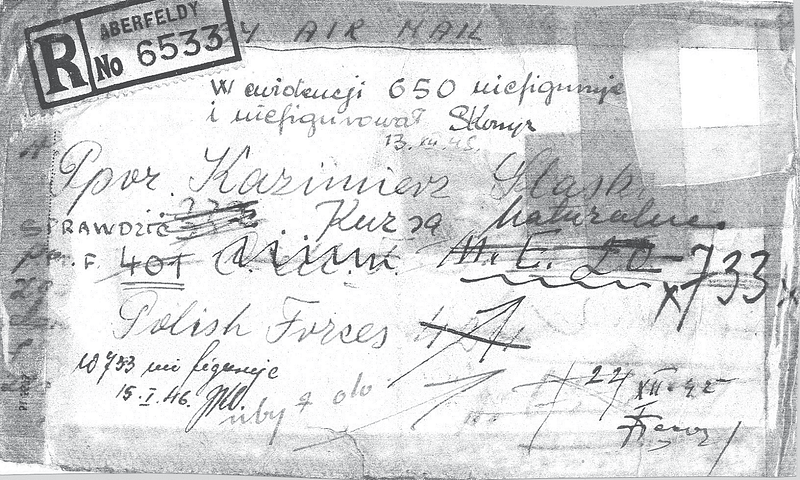

It was time to make a positive decision, so both Peter and I applied and received a place at the school in Alessano in southern Italy. Again I left Egypt, landed in Taranto and travelled to Alessano. It was at this time that I received a letter from my mother, the first contact since she had left my brother and I in Lwow.

By chance she had made contact with my commanding officer who had arrived in England. She sent him a letter and asked he forward it to me.

At the time I was in-transit travelling from Egypt to Italy, the letter taking nearly three months, and over a dozen field posts, before I received it. It was a miracle it ever arrived.

It was now Spring of 1946, and after more than six years of war I managed to make contact with her back in Poland. We finally managed to get her to England in the Spring of 1957. My brother and I had not seen her since that day in 1939, seventeen years earlier.

At the end of my final journey I disembarked at Liverpool docks and was transferred and stationed in Cawthorne, South Yorkshire.

I had survived a war in which millions of my fellow countrymen lost their lives.

My luck stayed with me because whilst awaiting demob I met Nancy and we were married on September 11th 1948; beginning an amazing partnership that would last for 63 years. I was promoted to the rank of a full Lieutenant in the same year and then parted company with the army.

After nine years as a prisoner, refugee and soldier I was finally a free and happy man.

Written by Mark Slaski.

Editing by Jonathan Este.

Compiled by John Stapleton

To contact email: mark@markslaski.com