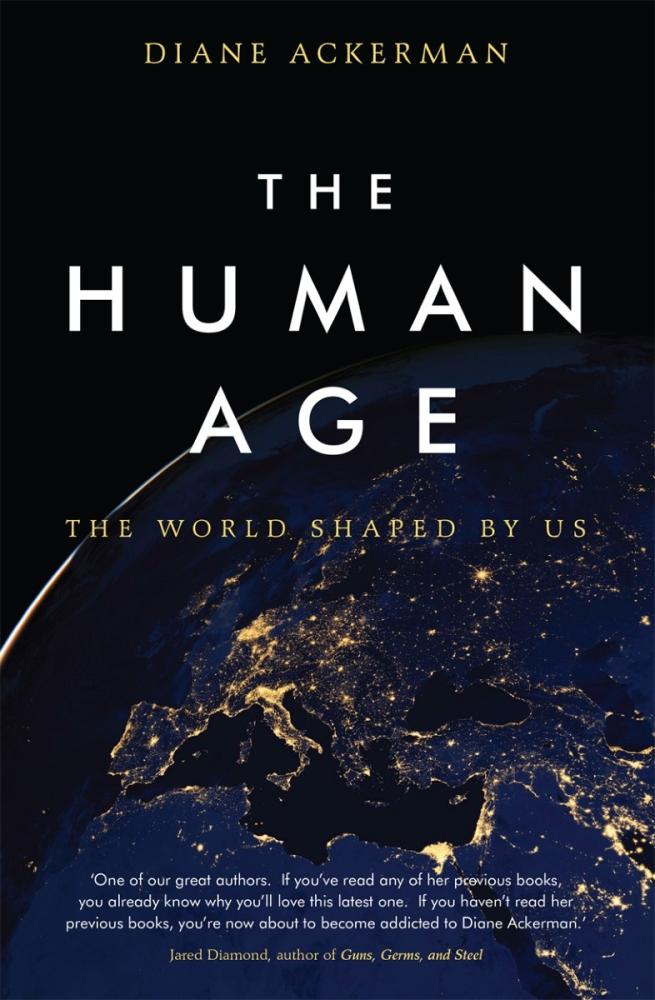

Our relationship with nature has changed, radically, irreversibly, but by no means all for the bad. Our new epoch is laced with invention. Our mistakes are legion, but our talent is immeasurable. Diane Ackerman, best known for her book A Natural History of the Senses, is one of the most lyrical, insightful and compelling writers on the natural world, and The Human Age is a landmark book. Humans have subdued 75 per cent of the land surface, concocted a wizardry of industrial, medical and technological marvels, strung lights across the darkness. We now collect the DNA of vanishing species in a ‘frozen ark’, equip orang-utans with iPads, create wearable technologies and synthetic species that might soon outsmart us. But the world remains as overwhelmingly beautiful as it ever was. In a darkening age, it is writers such as Diane Ackerman who are civilisation’s greatest treasures.

The ever truly brilliant Maria Popova writes in Brain Pickings, one of the world’s most eternally fascinating literary newsletters, documenting some of the world’s best intellectual forays on the road to enlightenment, writes of The Human Age: In the most memorable scene from the cinematic adaptation of Carl Sagan’s novel Contact, Jodi Foster’s character — modeled after real-life astronomer and alien hunter Jill Tarter — beholds the uncontainable wonder of the cosmos, which she has been tasked with conveying to humanity, and gasps: “They should’ve sent a poet!”

To tell humanity its own story is a task no less herculean, and at last we have a poet — Sagan’s favorite poet, no less — to marry science and wonder. Science storyteller and historian Diane Ackerman, of course, isn’t only a poet — though Sagan did send her spectacular scientifically accurate verses for the planets to Timothy Leary in prison. For the past four decades, she has been bridging science and the humanities in extraordinary explorations of everything from the science of the senses to the natural history of love to the slender threads of hope. In The Human Age: The World Shaped By Us (public library | IndieBound), Ackerman traces how we got to where we are — a perpetually forward-leaning species living in a remarkable era full of technological wonders most of which didn’t exist a mere two centuries ago — when “only moments before, in geological time, we were speechless shadows on the savanna.”

With bewitchingly lyrical language, Ackerman paints the backdrop of our explosive evolution and its yin-yang of achievement and annihilation:

Humans have always been hopped-up, restless, busy bodies. During the past 11,700 years, a mere blink of time since the glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age, we invented the pearls of Agriculture, Writing, and Science. We traveled in all directions, followed the long hands of rivers, crossed snow kingdoms, scaled dizzying clefts and gorges, trekked to remote islands and the poles, plunged to ocean depths haunted by fish lit like luminarias and jellies with golden eyes. Under a worship of stars, we trimmed fires and strung lanterns all across the darkness. We framed Oz-like cities, voyaged off our home planet, and golfed on the moon. We dreamt up a wizardry of industrial and medical marvels. We may not have shuffled the continents, but we’ve erased and redrawn their outlines with cities, agriculture, and climate change. We’ve blocked and rerouted rivers, depositing thick sediments of new land. We’ve leveled forests, scraped and paved the earth. We’ve subdued 75 percent of the land surface — preserving some pockets as “wilderness,” denaturing vast tracts for our businesses and homes, and homogenizing a third of the world’s ice-free land through farming. We’ve lopped off the tops of mountains to dig craters and quarries for mining. It’s as if aliens appeared with megamallets and laser chisels and started resculpting every continent to better suit them. We’ve turned the landscape into another form of architecture; we’ve made the planet our sandbox.

But Ackerman is a techno-utopian at heart. Noting that we’ve altered our relationship with the natural world “radically, irreversibly, but by no means all for the bad,” she adds:

Our relationship with nature is evolving, rapidly but incrementally, and at times so subtly that we don’t perceive the sonic booms, literally or metaphorically. As we’re redefining our perception of the world surrounding us, and the world inside of us, we’re revising our fundamental ideas about exactly what it means to be human, and also what we deem “natural.”