By Jeremy Aitken.

It is 2.45 pm on Monday late January in the heat of Summer. The Bankstown Water Tower shimmers against a blue sky as I turn onto the Hume highway. Passing car dealerships, fast food outlets, Australia Post’s distribution centre and News Corp I see a huge white plastic sign with a red oval on top. “Primo, Scrambles, delicious breakfast in a cup, just add an egg”. I have arrived. It was going to be a great day.

I’m on my last of my summer holiday study break, Uni starts in 2 weeks. I answered an ad on the student job board. “Labourers Wanted for Meat Processing work 28 dollars an hour flat rate, and staff discount.” I needed the cash and 10% off cured meat goods, sounded great.

The interview was straight forward. I was a permanent resident, had my own vehicle, was vaccinated, was relatively fit, could pass a drug test, had a fluorescent top but most importantly, I could start on Monday. To get psyched I watched “The Wrestler” where Mickey Rourke played an aging washed up fighter who ends up working in a meat factory.

I show my vaccination passport to security at the entrance before I am allowed in; a requirement for working at the plant. I put on my long sleeve fluro top and am escorted to a large room adjacent to a staff lunchroom where a masked man asks me if I’ve had any close contact and then gives me a rapid antigen test. It is negative. I am the only new one starting that afternoon.

I am then greeted by the section supervisor, Rahme, who in a mask is completely featureless. He speaks enthusiastically about how the night-time section boss is a good guy called Lipa. Rahme said not to worry as Lipa would show me everything that I needed to do. He then shows me where the coffee is and while I drink one, he gives me a brief rundown of what I am going to do this shift. I have been assigned to work in the cooking section of the plant, and as asked if I I had a forklift licence? No. Have I used a motorised pallet mover? No. Have I used a manual pallet mover? I have but some time ago.

Rahme takes me to the laundry area where a woman sizes me up and gives me clean hospital scrubs, medium. Rahme also gets me another facemask, two green hairnets and gum boots. The hairnets are colour coded to show what area I am working in; the facemask and hairnet are to be changed at my lunch break.

I put my scrubs on top of my clothes and tuck my pants into the gum boots, put my hairnet and face mask on and am ready. I feel like I’m going into an Intensive Care Unit at a hospital.

I followed Rahme upstairs and down white corridors lit by fluorescent lights. On the floor are yellow and black arrows directing the staff and along the walls are signs for social distancing. Along the walls there are colour pictures of staff wearing civilian clothes smiling with their names and hobbies written underneath them. “Chris, Pokémon hunter,” or “Haya, passionate amateur cook.”

Small rooms run off the corridor where people in lab gear and PPE (Personal protective equipment) looked silently at monitors. It all looked and felt like I was going into a high dependency ward at a hospital. There was no sound apart from the humming of the machines which grew louder as we approached the main processing area. I tried to take my bearings, but the corridors turned and twisted and made no sense.

Disorientated, I followed him down some metal stairs into a large anti chamber and walked through a large trough filled with red disinfectant liquid. I then washed my hands and sanitised them. I’m impressed by and how many more steps there are here to stop the transmission of disease than in the Covid testing facilities and aged care homes I had previously worked in. Rahme opened the doors, and I followed him out into the first part of the raw meats processing section.

The first thing that struck me is how white and clean everything was. The gun metal machines glow softly in the artificial light, and I thought I might have stumbled on to the film set of a heart clogging meat lovers’ version of Charley and the Chocolate Factory. I’m hoping the workers will burst into a reworked Opma Lumpa song and dance with frankfurters.

The second thought was just how noisy it is. I can’t hear Rahme at all. The third is the smell. I thought that there would be a smell of butchered meat, but it is weirdly neutral, no real smell of carcasses or flesh or the metallic smell of blood. It is very clinical and very mechanical. It is also cold and I’m happy that I’m wearing so many layers. There are people everywhere in PPE equipment working on conveyer lines putting what looks like pork into a large machine which is cutting it into slices, while others are taking out the slices, weighing them and putting them into plastic containers, and no one makes eye contact as we walk past.

We pass workers who are cutting what looks like sides of beef but in the fluorescent light it’s hard to guess with accurately. The meat looks translucent in the light, everything is industrial and disconnected, sterile, each cut identical. They put off cuts into metal bins to be taken away and transformed into some other meaty goodness.

I try to make mental notes of landmarks that will help me find my way out, everything and everyone looks the same in PPE. I see workers moving all kinds of raw meats from benches to containers or onto steel racks to be taken into the cooking area for the next processing stage. Some steel racks are loaded with thick sticks of white mystery meats that could be chicken, pork or turkey. I start to doubt my senses, it doesn’t smell or look like meat.

I finally get to my station which is the cooking area deep in the middle of the plant. Rahme introduces me to my supervisor, Lipa and I decide that I’m going to be called Jezza.

Lipa gave me ear plugs and a plastic poncho which I put on. I then put on blue gloves and a red helmet. I was starting to get hot.

“Number one is safety. You see anything that you don’t think is safe come to me. Any questions come to me. We need to make sure that there is absolutely no contamination, pregnant women eat this food and children, and it must be number one, OK? Change your gloves after you touch anything, OK!

“We have a lot of different nationalities here so sometimes someone might say something that you think is bad, don’t get angry, come and see me or HR.

“Don’t fight or be angry, it’s maybe a misunderstanding. Ok, we are all here to do a good job and make money for our families. Also don’t go anywhere near the cooked side. If you see any workers that are from that side then tell me and I’ll call them to close the doors, we should never see each other, OK!”

I nodded that I understood but I was finding it hard to hear with my ears muffled by the plugs. I looked at people with earmuffs jealously.

“Do not go anywhere without telling me. This is important! If you need to piss or to go anywhere you MUST tell me because I don’t want you locked in an oven.”

Of all the deaths I had imagined for myself I had never thought about going out in an industrial cooking accident. For the rest of my shift, I couldn’t get it out of my mind. I nodded in agreement. Lipa would know where I was always. Absolutely!

After the induction talk, he called over a dude a big friendly islander whose name I didn’t get, to show me the cooking area. It is overwhelming and huge. There are 33 massive industrial ovens each about the size of a shipping container which open at both ends. He explained that the raw meaty goodness from the production area, bacon, pizza meat, cabanossi, hams, salami – there are over 100 different products, is left on large metal trolleys in the cool room area. Our job is to put the trolleys into the oven on our side, the raw meat side, the meat is then cooked. The doors on the cooked side of the oven are opened and the meat is taken out.

The friendly dude then shows me the technique to push the trolleys into the oven. They are about 8-foot high and three wide with racks or trays on them depending on the product. You manoeuvre them to the oven door, not letting any meat fall off and avoid being hit by workers moving trolleys and then use momentum and your shoulder to get them in. It was difficult wearing gum boots. He asked me if I s am an Ozzy boy, I am and if I know any Samoans? I don’t. “You do now. Now you know two. Me and Lipa!”

The dude asked me a lot of questions. He was suspicious as to why I would want to do this work. “Why aren’t you married? Have you been a naughty boy? Is that why you are doing this work? Am I paying off my ex-wife? Samoan women aren’t interested in money, only family,” says the dude.

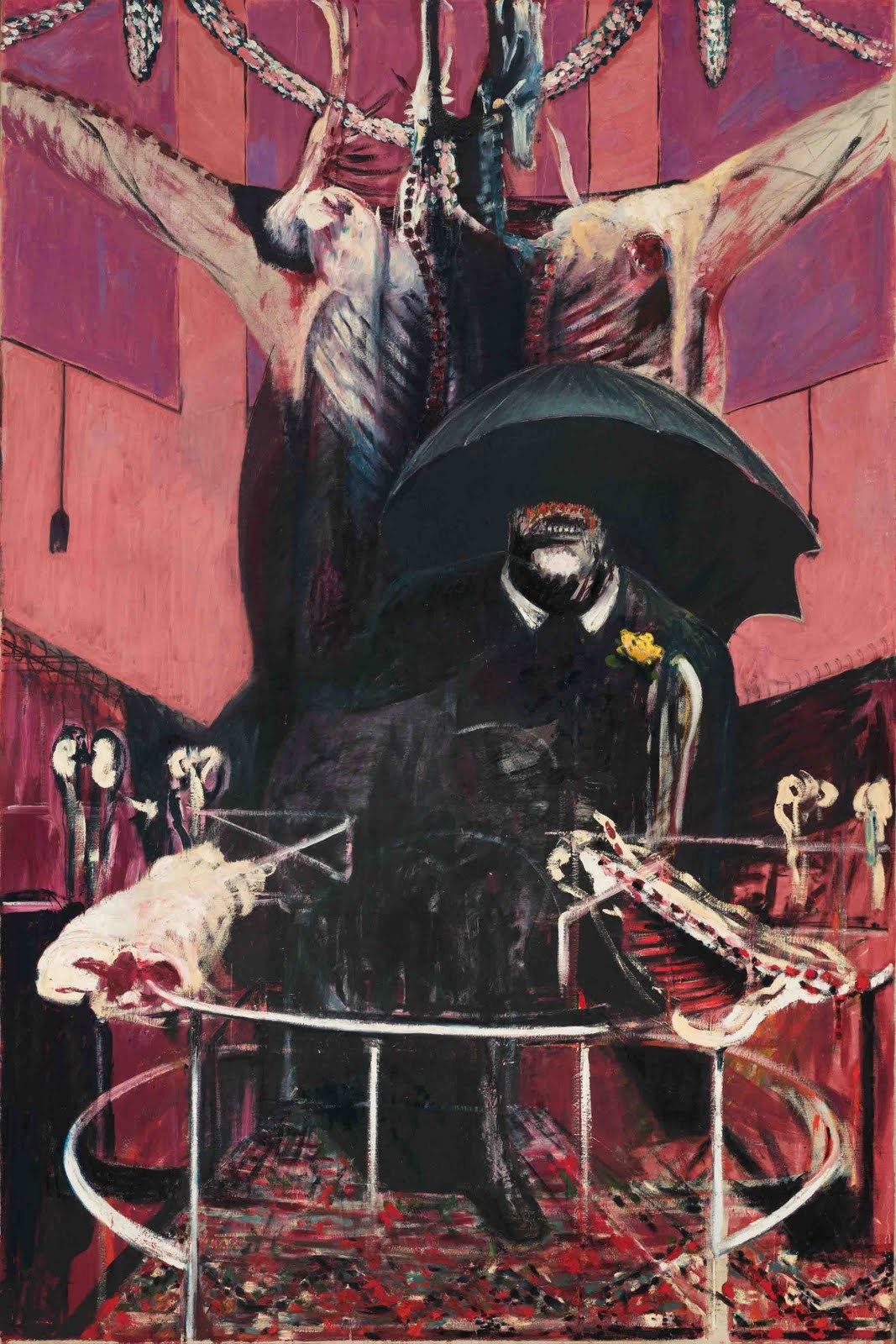

47 x 63 cm. Watercolour and Gouache on 300gsm Arches paper.

2019. Private collection.

I told him that I am trying to get fit and wanted to work out during the day. He said “You don’t need to go to the gym after pushing the trolleys.” He relaxed and then told me that the last Ozzy person hired left at the break and didn’t come back. They didn’t know what had happened to him.

I started pushing trolleys from the cool room to the oven. On one trolley were four racks of white tubes of sausage meat about a foot and a half long and 8 inches round. They looked like deep water prehistoric sea slugs, that had absorbed the artificial light. They wobbled as I pushed them, and I prayed that none would hit the ground.

I was hot. I couldn’t adjust anything, and I was wearing gum boots which did not give me any traction on the floor. I used my shoulder to push the trolleys and was super happy when I got them into the oven without losing anything.

It was now 5 pm and the other dude left: and it was me and Lipa. Lipa is a big guy, tall and walks with a slight limp. With PPE gear I couldn’t work out how old he was. I guess he was mid to late 50’s. He’d said he’d been there for 21 years, and normally worked nights but tonight they were short staffed, because of covid so he was working overtime, 5am till 5pm. He had seven children, I told him that was impressive, but he didn’t think so. “Small for an Islander family.”

His oldest was 34 and his baby 17. I didn’t get the gender of his kids. He momentarily adjusted his mask, and I could see that he sported a thin dapper moustache. I changed gloves and looked at Lipa’s work station. On the wall opposite each group of 10 ovens there is a computer control station that shows the product, cook time left and temperature.

Lipa moved up and down the huge ovens all night like he owned them. He constantly checked the control panel on the wall and to see if the product had been cooked and then opened up the oven door, took out a thermometer from the meat and compared it to the temperature on the cooking cycle. If the two were not correct, then the product was cooked again.

Like an ethereal being he appeared through the mist just as oven doors would open. Then I watched him disappear back into the steam and an alarm would ring to let the other side know that the cook was finished and their job to package it up had begun. Mysterious workers would remove the cooked meats from the oven, I would go into the oven and clean it and the process would start again. It went on like this 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, Covid hadn’t slowed down production. Nothing would stop the meat.

Around 8pm I’m starting to fade badly. I wasn’t sure what my body was doing but I felt like I was marinating under my clothing which was wrapped in plastic. I’m hot and when I go to the cool room to get trolleys my sweat condenses. I’m sick of pushing trolleys, hating meat and start to have job envy looking jealously at the dudes operating the automatic pallet lifters.

I wish I had shoes to grip on the floor, I wish I and earmuffs and not plugs because I can’t hear, and I wish I wasn’t so hot, and I want to go to the toilet. I’ve changed gloves about 20 times just to make sure and I’ve sanitised.

My eyes are stinging from the smoke from the wood that colours and flavours the meat and I can’t clean my eyes because I’m covered in plastic so I blink as furiously as I can, and the meat keeps coming. I get another trolley, this time it has red fleshy hot dogs on it dangling off racks. As I push it to the oven it looks like I’m staring through a curtain of meaty fingers.

Lipa asks me to start cleaning some of the ovens. I’m grateful for a change. I get a large broom with a hard plastic scraper and carefully walk into the oven. The floor is covered in a thick ooze of pink flesh, water and fat that has come off or out of the product, it is quickly congealing and glistens in the dim light. I walk carefully so as not to slip but my feet are unsteady, so I hold onto the wall for stability and am paranoid that the doors are going to lock me inside. I sweep and swear as I push the cooling slush into a drain that runs along the front of the ovens.

I forget to take off the metal grate on top and it soon blocks with pink stuff and fat. I get a hose and move the blockage down into a slush hole where I see it getting sucked down in a whirlpool of fat. I am now half deranged and disturbingly happy. I laugh thinking of Willy Wonker, only this is a river of pig fat and not chocolate. Then I yell out to Lipa to tell him I’m still in oven 19.

Another oven needs cleaning. It is dark inside and the fat on the floor catches a little light and in my mental state it looks like tiny pink gems sparkling in a river bed. I know what to do now and I pull off the grates at the oven’s entrance. I clasp my cleaning stick and go inside.

It goes on like this till 8.30pm when I am almost wishing I was cooked in one of the ovens. I show weakness and ask Lipa if I can go for a break. He nods and I am off.

I walk back trying to find my way through the cold section but everything and everyone looks the same. I walk to a section that is being cleaned and the floor is foaming white and runs in whirlpools into an escape hole in the middle of the floor. I look down at my boots which are covered in translucent white flesh and glisten with fat. I can’t work out how I got in and I am disorientated.

A kind worker points me to the direction of a door, and I push my way through to the anti-chamber I came in through. I rip off my plastic PPE, poncho and gloves and put them in the waste basket and try to pull up my jeans. I walk through the pink foot wash and swoosh my shoes around to clean off the bits sticking to them. I retrace my steps back down to the lunchroom.

I was stoked to get back and I drank as much water cold water as I could.

In the lunchroom the benches are separated by Perspex. Every second seat is covered with tape to stop people from sitting together. There are a mix of Islanders, people from the Sub-continent, Chinese and a couple of Eastern European guys who great each other in Polish. I can only guess at nationalities and gender by how they say “Hi.” I think that they are mostly men. Apart from a quick greeting the room is completely silent.

A man in a pink, fluorescent jacket that says, “Social Distancing Champion,” patrols the room to make sure that no one is breaking the rules.

“Johnno,” he says to a man sitting

“Nah.”

“Sorry bro,” he says, “That is normally Johnno’s seat and I thought you were him.”

I realise how hard it is to know who anyone is in PPE and face mask.

I got up to buy a sugary drink. At the snack machine three men were chatting about playing the cards at the casino. One small guy wearing a blue hairnet had a sure system to win by doubling up black.

“Play the odds, brother,” he said to another dude in a red hairnet.

“I never gamble,” he said.

“My system always wins.”

“Then why are you here?” said a tall Nigerian dude and everyone laughed.

“Keep my wife happy,” he said. And everyone laughed again.

“She doesn’t know you play the cards?” I said.

“She doesn’t care as long as there is money.”

“You married brother?” said the guy in the red hairnet.

“Not anymore,” I said

“Do you play the cards?” said the small guy in the blue hairnet.

“Yeah, but I always bet red.” I said.

“That’s why you’re not married.”

“I need a better system,” I said. “See you brother.” And I thought about playing the cards.

I go to the toilet and then wash my hands, disinfect them, put on a new mask, as my old one smells of pork, and a fresh hair net. I think about having a coffee but realise that I’ve got three hours before another break and decide against it.

I’m back at the workstation and all the ovens are running full. The air is thick with steam and smoke, and I feel like I’m in a dream. I see a figure coming out of the mist and read his name tag, it is Lipa. He hands me earmuffs and I’m happy. I knuckle respect him and then both of us change gloves.

An alarm goes off and Lipa goes to an oven and opens it. I see the white sea slug tubes I had wheeled earlier in the night now smoked and cooked transformed into red sandwich meat.

I went back and cleaned more ovens. I accidently sprayed water onto the ground and felt the splash back as fat and pig water trickled down into my boots. I walked down the corridor. The meat kept coming and the ovens needed cleaning. For the rest of the shift I felt as though I was on powerful mind-altering drugs where I hallucinated that the universe was made of endless trays of meat.

At midnight my shift was over, and I looked to see that the cool room was again full. I felt a sick pleasure and guilt at leaving, like I was having a day off from school but as I walked out, I realised that the job would never end and I should be happy that I helped keep the production line ticking along. Somewhere people would soon be waking up to enjoy a breakfast of bacon I helped cook. That thought made me really happy.

Content I found my way out to the change area. I ripped off my poncho and gloves. My hands were pruned, and my skin was raised. Taking off my scrubs I threw them into the laundry basket. My jeans stuck to my legs. My pants were wet and my t-shirt was sweat soaked. I was exhausted.

I walked outside to a full moon that silhouetted on a sign that promised a delicious hot breakfast in a cup.

At home I dumped my clothes and crashed completely spent and had vivid nightmares that I slipped in the oven, and no matter how much yelled and banged no one could hear me scream and I was cooked and made into processed Devon.

I woke up early and had black coffee and toast for breakfast.

Much respect to the tireless unsung heroes who keep the meat cooking 24 hours a day to get breakfast bacon and sausages to our tables to make sure we wake up to deliciousness, and all we need to do is add an egg!

I will never again eat a meatlovers pizza without thinking of the hard work you guys put into getting it to our table. Much respect, dudes!

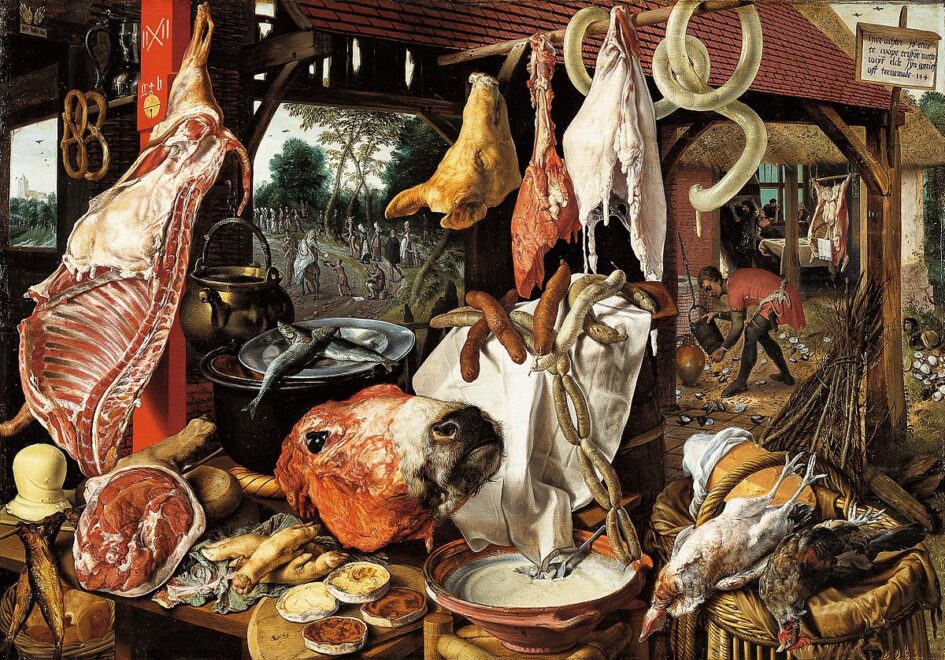

Feature Image: Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt

Alternative title: Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms. Pieter Aertsen. 1551.

When not testing for Covid or helping supply Australians insatiable demand for delicious meaty products, Jeremy Aitken is a full-time nursing student at the University of Western Sydney. In a previous life he was an English Lecturer at UNSW Global. He was highly commended for his semi-autobiographical novel, “The Bike” in the 2006 Vogel/Australian Award and his novel “Crystal Street’’ was published in 2017.

His story on working the Covid Line can be read here:

This piece was first published 20 March, 2022.