By John Aitken

John Aitken is a retired Science teacher who has a passion for WW1 military history. John has an extensive collection of Australian WW1 ephemera, including photographs of soldiers and letters they wrote to their family and friends back home. He is committed to ensuring that these soldiers are not forgotten and has subsequently compiled their biographies from researching their family histories and service records. Below is a sampling of his his latest research for a book he is compiling on the letters and photos of WW1 Australian service men.

Private Charles James Bradley, 11th Battalion, A.I.F.

On 4 August 1914, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany following Germany’s declaration of war on Belgium. In Australia, the outbreak of war was greeted with great enthusiasm and the nation pledged its support for Britain with an initial expeditionary force of 20,000 men, known as the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF). The 11th Battalion was formed in Western Australia within weeks of the declaration of war and together with the 9th (Queensland), 10th (South Australia) and 12th Battalion (a combination of 50% Tasmanian, 25% SA and 25% WA recruits) formed the 3rd Brigade, AIF.

When Charles James Bradley, commonly called Charlie, enlisted at Helena Vale, W.A., on 27 August 1914, he was among the first of the 1025 recruits who formed the newly formed 11th Battalion.

Charlie’s Mother, Mary Bradley.

Charlie, was born on 10 December 1881 near Wangaratta, Victoria, to Mary (née McDonald) and Patrick Bradley. He had seven surviving siblings, four older sisters, two older brothers and one younger sister and also three younger half siblings, two brothers and a sister1.

Prior to his enlistment, Charlie was well known round W.A. timber districts as a champion axeman, an all-round good fellow and a unionist from the Wellington Hewers’ Camp2, 3. At the time of his enlistment he was employed by Millar’s Timber and Trading Company as a blacksmith and survey hand where he earned 13/4 per day22. Charlie had previous military experience, having served with the Garrison Artillery in Western Australia for 3 years4.

When Charlie enlisted he was single, 33 years and 9 months old. He was allocated as a private to ‘B’ Company, 11th Battalion with the serial number 146 and undertook basic training at Blackboy Hill Camp where the 11th Battalion was being assembled4.

After just two weeks of preliminary training, ‘A’ and Charlie’s ‘B’ Companies embarked from Fremantle, Western Australia on board HMAT Medic on 31 October 19144, whilst ‘the rest of the Battalion embarked on the Ascanius4, 6.

The convoy of troopships carrying the Australians and New Zealanders arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, from 3 December onwards where the troops disembarked. The members of the 11th Battalion on board the Ascanius disembarked on 6 December in the evening and entrained for Mena where they arrived in the early hours of the following day. Because the Medic carried 400 horses, in addition to 1,400 troops, the ship was kept at sea until 11 December. Charlie with the rest of the troops, finally disembarked off the Medic at Alexandria two days later, where they entrained for Mena7.

HMAT Medic (Personal collection)

During its time in Egypt, whilst the men of the Battalion underwent strenuous training they also had the opportunity to visit the pyramids, ride camels, and spend time visiting the sights in Cairo.

On 1 January 1915, the eight company structure, A-H, of the Battalions that left Australia was reorganised into a four company system, each with approximately 200 men, in line with the British Army organisation. The eight companies of the 11th Battalion were consequently merged into four, A-D, with Charlie being moved from ‘B’ Company to ‘A’ Company6.

Shortly afterwards, on January 10, 1915, 704 officers and men of the 11th Battalion gathered on the Great Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops) near Mena camp, Egypt where they had their photograph taken, which became one of the most iconic of Australia’s war images of WW1.

Group portrait of all the original officers and men of the 11th Battalion, 3rd Brigade, AIF (Personal collection).

On 1 March 1915 the 11th Battalion embarked from Alexandria for the island of Lemnos on board HMT Suffolk where it arrived four days later. The Battalion spent the next seven weeks at Lemnos where the men spent their time on route marches, training, practising disembarkation, landings and attacks and the odd shore leave6. Charlie described Lemnos in a letter to his sister, Lou.

like it’s a lovely harbour surrounded by about the most bleak a desolate Island you would wish to see it’s [sic] chief product is rocks not a tree on it only a few fruit trees and they don’t look much the people are greeks [sic] they make a drop of wine and brandy also eggs is what they make a living from This was the first place I ever saw a herd of a pig [sic] tied up by the neck also they tie donkeys up by the front foot.

Men of the 11th Battalion and 1st Field Company of Engineers assembled on the quarter deck of HMS London, part of the fleet which carried the Australians from Lemnos for the Gallipoli landing at Anzac.

‘A’ Company, with Charlie, and ‘C’ Company, which were chosen to be in the first wave to land at Gallipoli, disembarked from the Suffolk, boarded HMS London and sailed from Mudros Harbour at 1.30pm on 24 April for Gallipoli.

The 11th Battalion, together with the 9th, 10th, and 12th Battalions, were the first units to land at Gallipoli on the early hours of the morning of 25 April. The 11th Battalion’s war diary recorded the event6.

LANDED 4.30 AM ON BEACH 1 MILE SOUTH OF FISHERMAN’S HUT, GALLIPOLI PENINSULA

landed under heavy musketry & machine gun fire and storm the cliffs about 300 feet high. Pushed back the Turks occupied the position occupied forward Ridge [sic] about 3/4 mile from beach & entrenched going to disorganisation consequent on landing on different parts of the beach and being mixed up with other units it was impossible to get the battalion together as the men were engaged in small parties right along the whole line of trenches.

In a letter to his sister Lou, Charlie described the landing8:

we were about 2 chains [40 metres] from the shore with rifle first followed by machine gun and quick fire all you could hear was bullets hitting boats etc the air was thick with them but it was grand, there was not many in the boats hit but when we landed we gained our objective as any body of Australians would. … it was great to see our men go straight into the thick of it treating them with contempt our job when we landed was to take lines of trenches on the top of the hill and we had to do it with the bayonet not a shot to be fired until daylight so we were [sic] captured the trenches including [deleted word] machine guns rifles and considerable ammunition also a couple of pom-poms

Charlie was among the many casualties during the landing, when he was struck by a bullet in his left thigh which caused a compound fracture of the femur. He later recounted to a friend in a letter from his hospital bed in Alexandria the circumstances surrounding his wounding2.

I got hit on the morning of the ‘glorious April 25.’ … We had advanced a good distance when I got my little present, which consisted of a hit from a pom-pom just above the knee, causing a terrible large wound, and breaking the bone in three places. While I was lying on my back just about 30 yards behind the firing line the noise of the machine guns and rifle fire was cruel, a regular hail of bullets passing over me, “while the shriek of the shrapnel and the bombardment from our warships added to the din. But our men just held on, and-oh! it was glorious;”

Original newspaper clipping from the W.A. Sunday Times, 1 August 19153 (Personal collection)

Charlie said of his wounding to Lou that it was8:

at daylight that I got hit I laid there for six hours before it was safe for the stretcher bearers to come near me ….. When I was picked up I was put aboard an Hospital ship and taken to Alexandra

In a later letter, Charlie spoke about the death of his closest friend who was killed shortly after he was wounded9.

my best pal fell shot at Gaba Teba not long after I was hit when I was hit he came and shook hands with me at the same time wishing me good luck and Lou what a grand young chap he was only about 24 years old and may God look over my dearest friend

Charlie was evacuated from Gallipoli on board S.S. Lutzow to Alexandria where he was admitted to the 15th General Hospital Alexandria on 29 April4. By the time he reached the hospital, sepsis had set in and the doctors immediately drained his wound in an attempt to reduce the infection4.

A room converted into a ward in an Egyptian hospital for wounded Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The beds are made of the ribs of the date palm leaf. On the left can be seen a mosquito net supported on a small frame work to cover the head and shoulders.

(Personal collection)

On 19 May 1915 in a letter to his sister Lou, Charlie wrote8:

I am at present in the Abbasieh hospital Alexandra with a very bad leg indeed all the flesh cut away above the knee and a hole that you could put a couple of cricket balls in and the thigh bone splintered I nearly succeeded in losing my leg the doctors very near were taking it off but there is one thing I am lucky in and that is having good doctors. All the same Lou I would gladly lose a leg to go through the same again it was glorious charging up a hill almost unclimbable on account of the steepness and driving Turks in front of us like a lot of wild cattle but the trouble was we could not catch them.

In another letter to his sister Nell, Charlie wrote10:

I wanted the Doctors to amputate it, when I went to the hospital first, but a Dr Heath a specialist, considered he could be save it ….

On 28 May 1915 he was operated on in order to drain the wound due to the sepsis and to set the fracture. Unfortunately the doctors were unable to save his leg, and it was amputated up to his thigh and 4 inches below the hip joint on 7 July4. On 21 July 1915, Charlie wrote to Lou telling her the news that his leg had been amputated but despite the pain, he would go through it again7.

…. well Lou I was laying on my back for ten weeks when what with the climate here and the bad break they had to take my leg off they took it off about eight inches from the hip I was under Chloroform eight times with it and I suffered great pain but I am real well and am sailing for England tomorrow to get properly well and to get a cork leg so I’ll be right I’ll tell you if I had the chance I would go through the same thing again for it was simply glorious seeing my gallant countrymen after I was hit they were grand as brave as possible and it their first go under fire.

In a later letter to Lou he wrote about the way he and the other wounded were treated whilst in hospital11.

…. the Officers got paid but the men didn’t I also consider it was rotten the way us wounded were treated in Egypt there was not a person of authority came to see how we were getting on or if we wanted anything they said they were giving us cigarettes but I can tell you Lou that the cigarettes I got averaged 1 packet a fortnight I don’t know what I would have done only for two Officers gave me £4/0/0 out of their own pockets a thing I was very grateful for as it allowed me to buy a little fruit and other necessities such as writing paper and cigarettes.

Charlie was discharged from hospital on Friday 23 July 1915 and embarked from Alexandria for England on board H.S. Loyalty4. Charlie recounted his voyage in which he saw the German submarine, U28, torpedo two British merchant ships, the Benvorlich and the Clintonia, on Sunday, 1 August 191512.

We had a bit of an exciting experience in the Bay of Biscay on Sunday Aug 1st about noon we sighted a German Submarine chasing a British merchant ship [most likely the Clintonia]. when she got close to us the submarine ordered our ships to stand by gave the merchant crew twenty minutes to leave the ship at this time another ship came to the assistance of the first (the fools) [the Benvorlich] they were also ordered into the small boats as soon as the crews were clear the Sub promptly sank the two ships she then came to within 70 yards of us but left us alone so we picked up at 17 survivors of [sic] out of first ship but there was 3 boats I afraid [sic] were lost in the sea at the time was fairly rough.

The Benvorlich was enroute from Manilla to London with a general cargo when torpedoed with no loss of crew14. The Clintonia, enroute from Marseilles to Tyne, England in ballast, was subjected to heavy gunfire, chased by U28 and eventually stopped where it was sunk by a torpedo. Ten lives were lost, 5 Europeans and 5 Lascars who were drowned when a life boat capsized, and a number of men were wounded during the chase15.

The Loyalty docked at Southampton at about 2pm and Charlie was immediately transferred by hospital train to Waterloo Station and then to the 2nd London General Hospital, Chelsea, where he was admitted to Ward 18, St Marks College4. He arrived at the Hospital at about 7pm, where10:

We received good reception, everybody seemed to think the world of the wounded soldiers here. I was greatly surprised, a [as] I thought they would be sick of soldiers here, wounded or otherwise, what I can see of things England is full of soldiers, coming from Southampton to London

Charlie commented about the difficulty in obtaining some of the necessities of life and the fact that he hadn’t been paid since April11.

There is a lot of Australian wounded here in England at the present they are treating the wounded fairly well but there is a lot of red tape about them they told us that anything we wanted such as shaving kit etc we could have as 3 weeks ago I told them I wanted a shaving kit but they haven’t sent it yet but chap wrote to them about the same thing the answer he got was to the effect that he would have to sign a requisition so I think one of these days I will write them and tell them politely to keep them I wouldn’t mind if I had some money but we have not had any money since 9th April.

By 6 October 1915, Charlie was out of his bed and enjoying the sights of London16.

I’m doing grand these days I’m driving continually about London and district in motor’s [sic] going to teas etc I went yesterday with a Mrs Horn a lovely old lady for a drive all over the place and had tea at the Trocadero Restaurant my word it’s alright we had a lovely tea the only thing is everybody stares at us blokes and especially me with the shank off but I’m getting quite used to it now

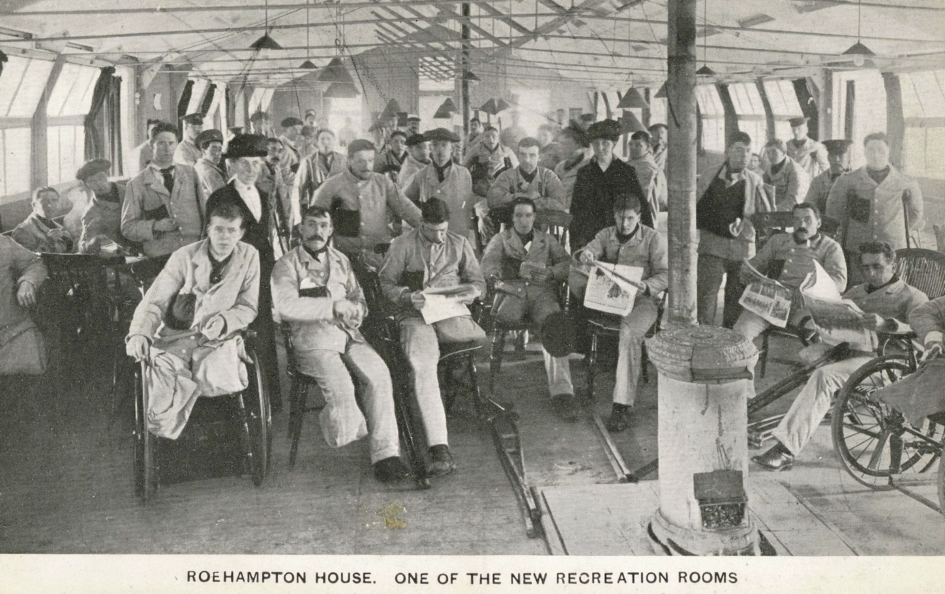

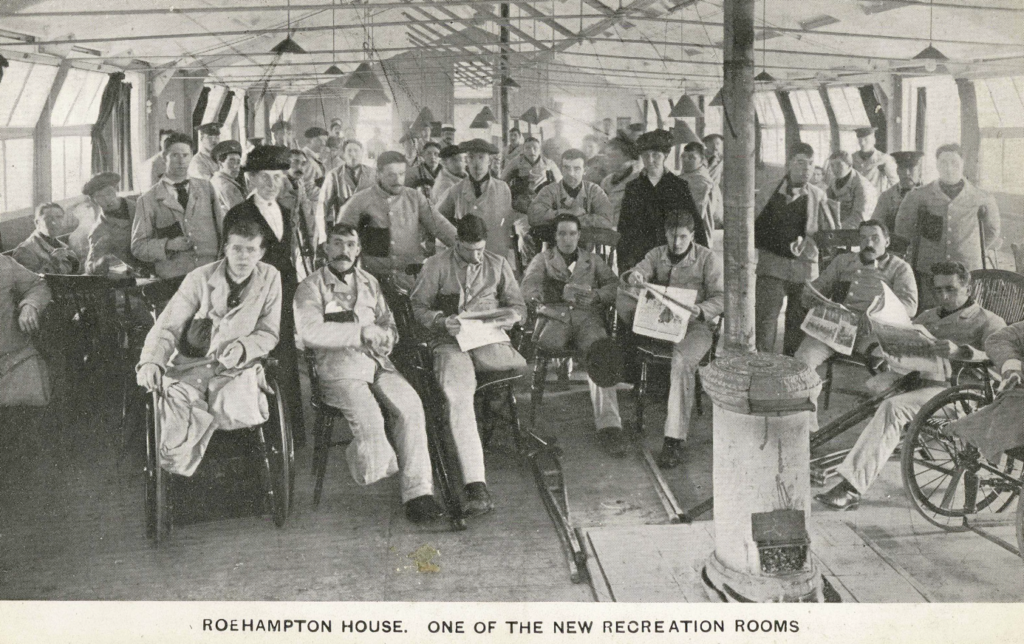

A ward at the 2nd London General Hospital. Note the New Zealand soldier in the foreground wearing his lemon squeezer hat17. Following his discharge from the hospital on 11 October 1915, Charlie was transferred to the King Georges Hospital Queen Mary’s Roehampton House. Queen Mary’s Roehampton House was established in 1915 as a place of rehabilitation for sailors, soldiers and airmen and specialised in the fitting of artificial limbs.

I left the Chelsea Hospital and I’m now at Roehampton House a place set aside exclusively for artificial limbs there are at present about 220 patients here some wanting arm some legs some both….. there is a lot of Australians in England now but so far they’re only three of us in this place. yet but there are a good many more here in England with limbs off 18

During his stay at Roehampton, Charlie managed to visit the theatre and strike up a romance with a young woman, which unfortunately didn’t go very far.

I go to a good many theatre’s also I get free tickets I have a young Lady here her and I usually go together she is lovely she is a South American half spanish [sic] but has lived in England since she was three years old she is at the Academy of Music now learning the Piano, and Lou leg or no leg all I have to do is to say the word and I have a wife but I think she would be sacrificing too much to marry me she is only young yet but she is a grand lovely and respectable young lady her name is Constance Wileman if I was alright nothing would give me more pleasure then introduce her to my sisters as mine19

Charlie was discharged from Roehampton on 5 December 1915 still without an artificial leg having been fitted. He was granted one month’s furlough which he spent sightseeing London before embarking for Australia on 12 December 1915 on board the Star of England from Portland, England4. In a letter to his sister Lou three weeks after he arrived at Perth on 23 January 1917 he wrote of the voyage20:

after a voyage out lasting six weeks as far as the boat was concerned we had a good trip but for food it was the worst had since leaving Australia 15 months ago as the meat on board was unfit to eat also the butter we had to throw it overboard almost every day any way we arrived here about three weeks ago the name of the ship was the Star of (Starvation) England

In the same letter, he also expressed his disappointment at the lack of welcome home reception that the ship received20.

nobody knew we were arriving consequently no one to meet us. I would not mind only we are credited with being welcomed home etc: we were not recognised at all we may just as well have stayed in England for all people cared.

Following his arrival in W.A., Charlie was admitted to the No.8 Australian General Hospital, Fremantle where his stump was treated. He had still not been fitted with an artificial leg at the time he wrote to his sister on 15 February 1916. During his stay in the hospital to visit his brothers, Patrick and Jack, who lived at Kwolyin, a small town in the W.A. wheat belt, east of Perth, and friends on a number of occasions. He mentioned that he had been offered a position in a shipping office but of course do not feel inclined to except [sic] same yet20.

In March 1916, Charlie visited the Wellington Timber Mill where he was warmly welcomed home by his friends and colleagues. The West Australian Worker, 31 March 1916, reported that21:

The welcome home social organised at Wellington Mills in honor of Charlie Bradley was a pronounced success. Charlie was well-known on the mills prior to going to Gallipoli. The world war has left him minus a leg, and supported by a pair of crutches, we are reminded that owing to the barbarism still in mankind Charlie and thousands of his fellows have to leave the ranks of active producers. ….. Charlie Bradley has, like most of the timber men, played his part. His brother Pat. president of the Kwolyn branch of the A.L.F., has also enlisted

Charlie was finally discharged from the hospital on 28 July 1916 where it was reported that the stump had healed and he had been fitted with an artificial limb. Following his discharge from hospital he was transferred to the Details Camp. He was discharged from the A.I.F. at Perth on 2 October 1916 as permanently unfit due to his left thigh being amputated after 2 years and 35 days service; 1 year and 90 days of which had been spent overseas22.

Following his discharge, Charlie received his deferred pay of £35, and was granted a pension of £3 per fortnight for the first 6 months and 45/- thereafter22.

As Charlie felt he could not return to his former occupation as a blacksmith and survey hand he determined to learn a new trade that he could meaningfully follow.

Following his discharge Charlie travelled to Melbourne where he lived with his half-brother, Martin Leacy, and sister, Mary (Nell) Helena at 170 Powlett St, East Melbourne. Whilst there, he had some alterations and repairs made to his artificial leg22.

In November 1916, Charlie returned to his home town of Carraragarmungee, 15km north east of Wangaratta, where he was given an enthusiastic public welcome at the Carraragarmungee Public School on 8 November 1916. The Wangaratta Chronicle reported there was a very large attendance of friends, well-wishers and admirers of our first returned Anzac hero23.

Charlie returned to Western Australia where in January 1917 he continued to have ongoing problems with his artificial leg, to such an extent that he was unable to use it. His request for a new leg was granted and it was agreed by the authorities that it would be paid for by the Western Australian Division of the Red Cross. As he was unhappy with his previous leg which had been made in Perth, he applied to have the new one made in Melbourne as he considered that they were superior to the ones made in W.A. On 7 April 1917, Charlie sailed from Fremantle for Melbourne, where arrangements were made for his replacement leg to be made at the Commonwealth Artificial Limb Factory22.

He spent the rest of 1917 commuting between Melbourne and Londrigan, 11km north east of Wangaratta. By August 1917 he had received his new leg and had found it to be a great improvement on his former one22.

In September 1917, Charlie was corresponding with the State War Council, which controlled the administration of war patriotic funds in Victoria. He was attempting to obtain assistance to go into some small business of his own, rather than working for an employer. The Council, however, had suggested that he obtain some form of technical training which would make him ’employable’. In a letter to a Mr. D. Barry, State War Council, 10 September 191722, he stated that he was not interested in obtaining technical training and that:

my idea in not going in for technical training is, that I have learnt one trade [Blacksmithing]. I consider in another branch of industry, a man would always be a slow worker and not competent of working against faster and sound man, also that ordinary employer’s patriotism is in their own pockets not in the interests of returned Soldiers or other employees.

During 1917, Charlie learned wool sorting for about eight months under the vocational training scheme. In late January 1918, he began work at a Wool Sorting Works at Richmond. Apparently he didn’t enjoy the work as after a few days, he reported back to the Vocational Training Section and asked to be allowed to return to the class. The reason he gave was that he had broken down in his work through heart trouble. His application was declined on the basis that his past performance proved that he was physically fit for work in the Woolshed and that if he was unable to do comparatively light work there was no point in him persisting in training him22.

In November 1917 Charlie, whilst living with his relatives at Londrigan, applied to the State War Council for a loan of £300 from the Australian Soldiers’ Repatriation Fund, in order to purchase a hairdresser and tobacconist business at Wangaratta. He said it was his intention, if his application was successful, that he would be involved in the tobacco side of the business and he would employ a man to do the hairdressing. Unfortunately, Charlie was unable to proceed with the purchase as the Fund had a limit of £150 for such ventures, which seemed very unfair when soldiers settling on the land could apply for a £500 loan22.

In February 1918, Charlie completed a vocational training course in boot repairs with the Brighton Readaptation Society, which helped veterans with “physical or mental disability” to regain their independence. The Society offered free training in new trades, assistance finding employment and a weekly allowance to supplement their pension until they found stable work.

Following the course, Charlie obtained two days a week work in a Collingwood boot repairing shop where he continued to hone his skills in boot repairs under the tutelage of the shop owner22.

Charlie began his own business at 140 Langridge St., Collingwood on 17 July 1918 when he bought an existing boot repair business for £25. As Charlie had spent his deferred pay of £35, mainly on two pleasure trips to Western Australia, he only had £5 remaining. He borrowed £10 from a friend and owed the vendor of the business £5. He applied for £10 by way of a gift and a £17 loan from the Department of Repatriation on 3 September 1918 to enable him to repay the loan and money owing to the vendor and for the purchase of leather and tools22.

Charlie had every confidence that he would make a success of his business. In a letter to the Department of Repatriation in relation to a loan, he said I have no reason to fear that I can’t do alright. (Bradley, Charles, Letter to Mr Groom, Department of Repatriation, dated 25 July 1918). A Mr. W. Groom manager of the Brighton Society for the Readaptation of Soldiers, supported Charlie’s application and wrote22:

I have formed a good opinion of Mr Chas Bradley, I found him eager to learn, and deeply interested in his work, has completed his training and now a good tradesmen. I have confidence in him as I know him to be competent to carry on. I saw the locality and business myself last week and feel sure he will succeed in the same.

Charlie’s application was successful and he was able to repay the loan from his friend and the balance owing to the vendor. He ended up, however, with a debt of £14.17.0 to the Department, which had to be repaid in instalments22.

After 30 months in the trade he began making boots until the end of 1920 when the demand for boots declined and he was forced to sell his stock at a loss22. He had also injured his hand through a fall when his crutches slipped from underneath him, which made it difficult to handle his tools. In addition his trade was further affected by four other boot makers who had opened businesses in the area. As a result, he experienced financial difficulties and was in arrears in repaying his loan to the Department and had to sell his business to satisfy his debts22.

Following the closure of his business, Charlie returned to Londrigan, 11 km north east of Wangaratta, in 1921, where he spent most of the year with family. In August he wrote to the Department of Repatriation asking for further financial assistance in order to recommence working as a bootmaker in Melbourne22. It is unsure of whether his application was successful, however, in the meantime, he received a war gratuity grant from the Government which would have assisted him in re-establishing his business22. In April 1920 the Commonwealth Government passed the War Gratuity Act 1920 which enabled ex-service personnel or the dependents of those soldiers who had died as a result of war injuries to a gratuity based on their length of service24. Charlie would have received 1/6 per day of overseas service. According to his sister Lou, who was later the administratrix of his estate, Charlie had used his War Gratuity for business and living expenses22.

In October 1921, Charlie’s clinical card was forwarded to Wangaratta as he had moved there from Melbourne. In November, the Department of Repatriation requested its return as Charlie had moved back to Melbourne22.

Despite his initial satisfaction with his new leg, Charlie experienced difficulties with it and by August 1921 he was unable to use it effectively for walking. Apparently, the bucket of the limb was too small for the amputation and caused pressure on the end of the bone and it would not remain in position, which meant he was practically unable to use the leg. Consequently, he visited the Commonwealth Artificial Limb Factory in Melbourne where the necessary alterations were made22.

By 1922, Charlie had established another boot repair business at 406 Wellington St, Clifton Hill22.

On 14 February 1923 Charlie was admitted to the Caulfield Repatriation Hospital where he underwent two operations to drain his stump of pus that had accumulated in the wound. He was discharged on 10 April 192322.

Sadly, Charlie died at Melbourne Hospital following an operation for appendicitis on 4 April 1924. The Department of Repatriation contributed £10 towards his funeral expenses and the remainder came from selling his assets in his boot making business. He died insolvent. At the time of his death, even though Charlie didn’t owe the Department of Repatriation any money, the Department had the gall to suggest, that as Charlie had been a single man, that his sister, Lou,, be approached to see if it was practicable to recover his tools in order to repay the original gift of £10 to establish his business in 1918. The Department appears to have been both insensitive to Charlie’s family’s grief and had little understanding or no idea of the nature of a gift. This, however, was not possible as Lou had already sold his tools in order to pay for the funeral. In a letter from the Department’s Loan Officer, it was suggested:

At the time of the grantee’s demise he was insolvent, and as the goods purchased with the amount advanced by gift were chiefly leather and other material used in the boot repairing business, it is suggested that no further action be taken to recover [the gift]22.

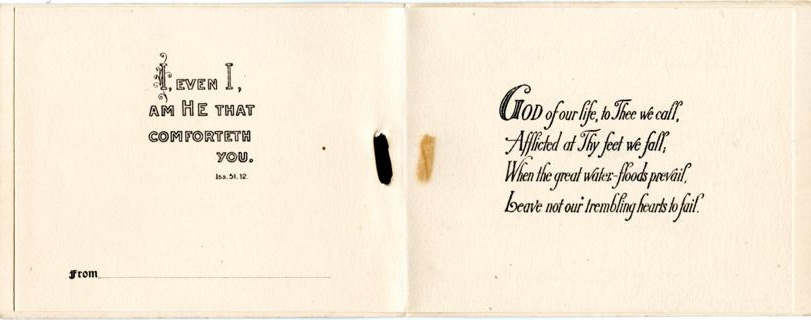

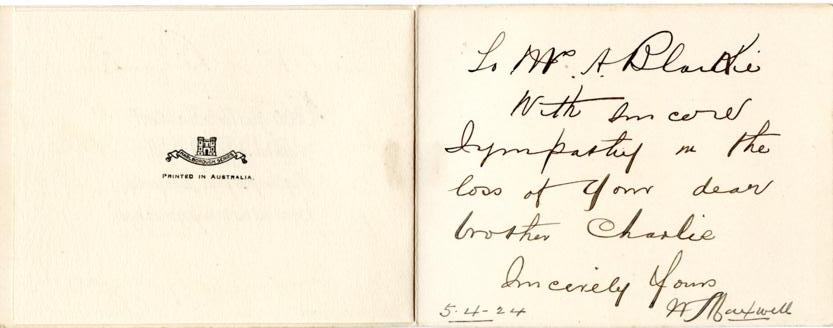

In a sympathy card sent to Lou following Charlie’s death, James McDonald, a family friend, wrote25:

what a terrible thing for him to be cut off in the prime of life especially after all the poor fellow went through, having fought, bled & mutilated for his country. I little thought the morning he left here so cheerful & full of life that it was the last time I was to see him …. He said he was quite happy now, as he had the motor & could get about as he liked.

The following two unidentified photos were included in Charlie’s letter and medals.

Charlie’s death was another tragic blow for the Bradley family, who had previously lost two of their sons/brothers, Raphael Duncan and Patrick William, during the war. 1798 Private Raphael Duncan Bradley, 57th Battalion (formerly No. 1019, 23rd Battalion), was killed in action at Estaires by enemy artillery on 11 July 191626 and 5565 Private Patrick William Bradley, 28th Battalion, died of wounds, France, 4 April 191726.

Charles James Bradley’s biography was compiled by John Aitken, 27 February 2022.

References: All references viewed 27 February 2022 by the biographer.

- Charles James Bradley, Naytes Family Tree, http://www.ancestory.com.au/

- Heroes of Gallipoli Soldiers’ Letters to “The Sunday Times” —A Trooper Breaks Into Verse—”My Little Wet Home in a Trench” — A Nungarin Farmer’s Graphic Story (1915, August 1). Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 – 1954), p. 12 (Second Section), http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57792623

- Timber Topics. (1915, August 27). Westralian Worker (Perth, WA : 1900 – 1951), p. 4., http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article148349490

- Charles Bradley, National Archives of Australia; Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3113905

- 11th Battalion A.I.F. – Cheops Pyramid, https://11btn.wags.og.au/index.php/11bn-home/chronology/69-1914-august

- 11th Australian Infantry Battalion’s war diary August 1914 – April 1915, AWM423/28/1, Australian War Memorial, http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1341877

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 21 July 1915, personal collection of the biographer

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 19 July 1915, personal collection of the biographer

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, October 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Mary Helena (Nell) Bradley, 3 August 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 2 September 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 9 August 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Belford, Walter C. (1940). Legs-eleven : being the story of the 11th Battalion (A.I.F.) in the Great War of 1914-1918. Imperial Printing Company Ltd, Perth, Western Australia.

- SS Benvorlich, WreckSite, https://wrecksite.eu

- SS Clintonia, Wrecksite, https://wrecksite.eu

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 6 October 1915, personal collection of the biographer

- Roehampton House, Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/robmcrorie/8711041978/in/photostream/

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, undated 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 6 November 1915, personal collection of the biographer.

- Bradley, Charles James, Letter to Margaret Louisa (Lou) Blaikie, 15 February 1916, personal collection of the biographer

- Timber Topics. (1916, March 31). Westralian Worker (Perth, WA : 1900 – 1951), p. 1., http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article148342614

- Charles Bradley, NAA:B73, R11584, National Archives of Australia, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=20877319

- CARRARAGARMUNGEE. (1916, November 11). Wangaratta Chronicle (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), p. 5 (Mornings). http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92005204

- War Gratuity Act 1920, Federal Register of Legislation, Australian Government, http://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C1920A00002

- McDonald, Jas to Margaret Louisa Blaikie, dated 9 April 1924, Personal collection of the biographer

- The AIF Project, http://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/index.html

Private Charles James Bradley, medals, ID disc and lanyard, Returned Service badge, Victorian Limbless Soldiers Association badge and his collar badge.

Above: Charlie’s medals, 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Allied Victory Medal.

Left: Clockwise top left, Charlie’s:

- Returned Service badge (No. 27759)

- Identity disc and lanyard

- Victorian Limbless Soldiers Association badge (No.556)

- Collar badge