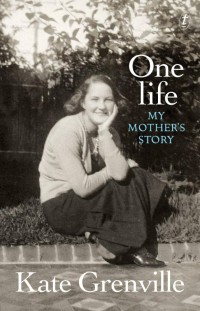

When Kate Grenville’s mother died she left behind many fragments of memoir. These were the starting point for One Life, the story of a woman whose life spanned a century of tumult. For many years, Nance recorded her memories in ordinary exercise books. The neatly handwritten stories start confidently, peter out after a few pages, and give way to Italian language exercises and other scribbled notes. One Life is an act of great imaginative sympathy, a daughter’s intimate account of the patterns in her mother’s life. It is a deeply moving homage by one of Australia’s finest writers.

In many ways Nance’s story echoes that of many mothers and grandmothers, for whom the spectacular shifts of the 20th Century offered a path to new freedoms and choices. In other ways Nance was exceptional. In an era when women were expected to have no ambitions beyond the domestic, she ran successful businesses as a registered pharmacist, laid the bricks for the family home, and discovered her husband’s secret life as a revolutionary.

“I’m so grateful to my mother,” Grenville says. “The books I am most proud of having written – particularly The Secret River and Sarah Thornhill – are straight out of family history. She told me those stories endlessly as a child, and I’m very ashamed of the fact that I would glaze over as Mum would start in again on Solomon Wiseman. I was writing The Secret River when she died, so unfortunately she never saw it but I can remember her saying, ‘This will be your great book,’ and I’m very lucky she lived long enough for me to thank her.”

Book reviewer Caroline Baum’s wrote:

In a recent interview, Kate Grenville said this was the hardest book she has ever written. Based on her mother’s own frustrated and unfinished attempts at writing her life, Grenville has undertaken the delicate task of telling the story of a woman that many readers will recognise as emblematic of a generation: someone who grew up with not enough love from her parents, not enough education, not enough choice. But who made something of herself. Never complained, expanded her own horizons through curiosity and reading and made a meaningful existence out of hard work, determination, quiet dignity and resilience.

Grenville handles the material of her mother’s unhappy marriage, her professional disappointments and slights as well as her growing political awareness of social issues with sensitivity and restraint. She captures the times through details honed from years as a novelist writing stories set in the deep past, bringing to life what could seem like a faded sepia photograph vivid with colour and atmosphere. Life was hard for young people in the nineteen thirties and pleasures were modest: a game of cards, a night at the pictures. No one had much, shoes were lined with newspapers, gloves were darned when their tips wore through. Hours were long, pay was low and women were hemmed in by limited opportunities no matter how much initiative and promise they showed.

Without glorifying her mother as a martyr, Grenville honours Nance’s integrity and strength of character. Without patronising her, she shows us her innocence and her mistakes, combining a clear-eyed gaze with daughterly respect and tenderness. The result is a tribute not just to her own mother, but to the many Australian women of that era who strained to find fulfilment when opportunities were limited. We can only be grateful at how much things have changed.