By Professor Ramesh Thakur

This is not an article I had expected, intended or wanted to write. I have politely declined requests to write on the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in relation to the current crisis in Myanmar and the climbing civilian death toll. The turning point was visuals of people with R2P banners, T-shirts, umbrellas and candle-lit vigils, as in the photo accompanying this article. The images have touched my conscience and should pull at the world’s conscience.

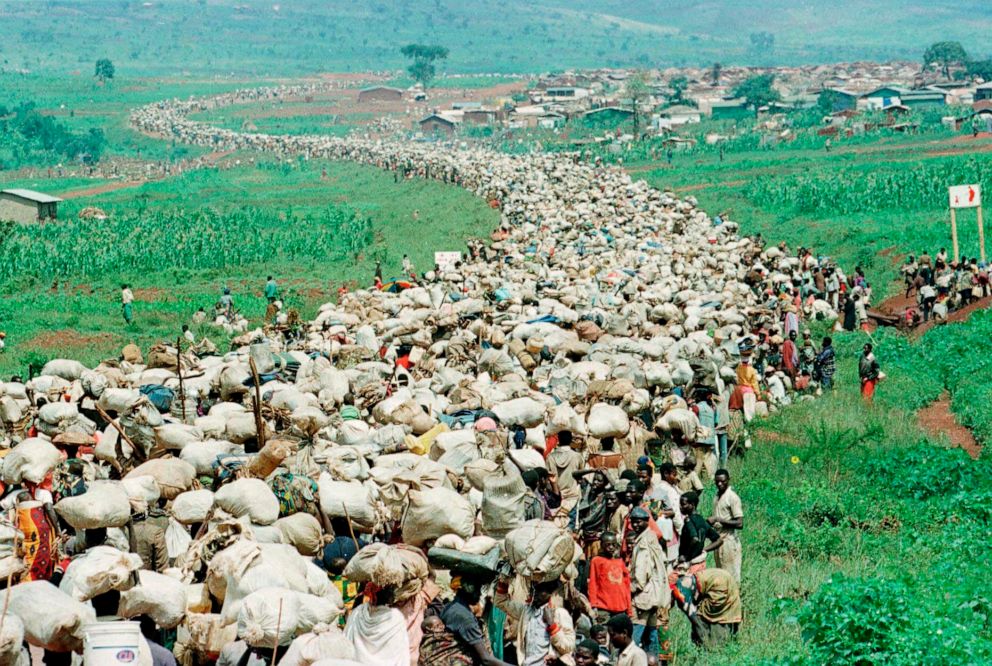

Let me explain. A number of humanitarian crises erupted in the aftermath of the end of the Cold War and were dealt with differently on a case-by-case basis, from the Rwanda genocide to the unilateral NATO military intervention in Kosovo and the UN-authorised peace operation in East Timor. The variable responses, uneven results and ensuing controversies highlighted how the global consensus on the circumstances in which it is both legal and legitimate to use force within and across borders had fractured.

Responding to a call by United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, whose own conscience never quite recovered from the killings in Rwanda and Srebrenica that happened on his watch as the UN peacekeeping chief, in 2000, Canada assembled an international commission, co-chaired by former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans and former Algerian diplomat Mohamed Sahnoun with 10 more of us as commissioners, to search for a new normative framework.

We developed R2P as the central organising principle for the world to respond, acting through the UN, to mass atrocities. We redefined sovereignty as responsibility that is located primarily in the state but residually in the UN.

The core R2P principle was adopted unanimously at the world summit in 2005 and became official UN policy. It has been clarified and refined continually since then, rejigged in the language of three pillars, but fell out of favour after the UN-authorised and NATO-led R2P intervention in Libya in 2011. While the UN had responded as it was meant to under R2P, NATO powers abused the UN authorisation to transform the mission from civilian protection into regime change.

Importantly, however, because R2P speaks to a demand-driven urge to respond to conscience-shocking atrocities in an imperfect world in which some leaders behave badly to brutalise civilian opposition, the principle itself has never been seriously questioned. It remains a readily accessed normative tool for channelling individual outrage into collective policy remedies.

From the very start, we advocated for it on the grounds that, unlike humanitarian intervention, it puts the human protection needs of victims ahead of the rights and privileges of intervening powers.

Academics in comfortable Western universities continue to criticise R2P as an instrument of neocolonial white powers who camouflage darker geopolitical and commercial motives in the language of humanitarian concerns. The photos from Myanmar calling on the world to honour the R2P principle is the most poignant riposte possible by victims themselves.

So much so that doing nothing would be yet one more shameful betrayal of our common humanity at the most basic level. The pleas for credible and effective R2P action clearly show the extent to which the power of R2P as a mobilising norm has penetrated deeply and taken root in civil society in countries in need. Even more importantly, victims see in R2P the potential for international action that challenges and changes the facts on the ground in Myanmar.

Silence in the face of the atrocities is immoral and condemnation is an inadequate response to the deliberate and large-scale use of deadly force by Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw.

Many people make two common mistakes about R2P. Its first pillar refers to actions by a state that include the use of force if necessary to protect at-risk groups. The second pillar is international assistance to the state, with its consent, to build R2P capabilities.

The third pillar anticipates circumstances in which escalating coercive action may be taken by outsiders if the state is unable or unwilling to discharge its responsibility to protect, or is itself the perpetrator of atrocities. But even pillar three prioritises peaceful means and contemplates the use of force only as the very last resort.

The Tatmadaw have probably been caught by surprise at the breadth, depth and persistence of protests. We don’t know if they have the unity or the stomach to go all in with mass killings. At this stage, consequently, a return to civilian rule cannot be ruled out, but the legacy of past military brutality means indefinite military rule is also possible. In this delicate balance, how can outsiders incentivise internal political-military forces and nudge ASEAN, the only regional organisation that matters, into action?

The five permanent members of the UN Security Council (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States) have a collective vested interest in keeping security decisions within the Security Council and freezing the General Assembly out. However, I previously noted the assembly’s recent bursts of independence from the council in the selection of the secretary-general, election of judges to the International Court of Justice and the adoption of the nuclear ban treaty.

![Anti-coup protesters run to avoid military forces during a demonstration in Yangon, Myanmar on Wednesday March 31, 2021 [File: AP]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AP_21090255990729.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

There is precedent for the General Assembly to meet under the ‘uniting for peace’ formula under resolution 377(V) when the Security Council is deadlocked. Such recourse to the UN’s unique legitimacy, which resides in the assembly from universal membership to counterbalance the geopolitical heft of the council, was recommended in our 2001 commission report but ignored in the 2005 world summit document. It might be time to rescue and activate it. ASEAN should take the lead in mediating the crisis, offer its good offices, engage both the Tatmadaw without legitimising it and Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy without alienating the Tatmadaw, and, if the Security Council abdicates on its solemn R2P responsibility, transfer the issue to the General Assembly under resolution 377(V).

In the current unrest, any external military intervention in Myanmar would greatly worsen the humanitarian crisis and should not even be on the table for consideration. But there are other instruments in the UN toolbox that can and should be used. These include diplomatic rebukes by means of a resolution, targeted sanctions on senior military officials and businesses, arms embargoes, and a referral to the International Criminal Court. The threat of ICC referral could be leveraged to persuade the generals to vacate the governance space without further bloodshed.

Professor Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, is emeritus professor at the Australian National University and director of its Centre for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament. He is one of Australia’s most distinguished academics. Articles by Professor Thakur published in A Sense of Place Magazine can be found here. This story was originally published in The Strategist and is republished here with the kind permission of the author.