By Professor Ramesh Thakur

On 5 May, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health published an important report on Norway’s experience of dealing with the Coronavirus crisis. The text that follows is a verbatim extract of the equivalent of the executive summary from the report, using Google translation.

Note

COVID-19-plague: Knowledge, situation, prognosis, risk and response in Norway after week 18 (Oslo: NIPH, 5 May 2020), https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/c9e459cd7cc24991810a0d28d7803bd0/notat-om-risiko-og-respons-2020-05-05.pdf.

Main message

It’s been six months since the previously unknown coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 first infected humans and the pandemic with covid-19 disease was on. Much knowledge has been gained: The virus is spread mainly by saliva drops directly into the face or via hands and objects to the face. No one was immune. The spread potential is moderate (R0 around 3), which indicates that an epidemic will hit 50–70% of the population before it burns out. The disease picture is very varied and can be: not noticeable infection, colds, flu-like illness, pneumonia, acute lung failure and death. Everyone can get serious illness, but the risk of dying from the disease can be over 1:10 in the elderly, less than 1:1000 in young adults and less than 1:10,000 in children.

Although individual severity is quite low, an uncontrolled epidemic will result in an overall large burden of disease with hundreds of thousands of sick and tens of thousands of hospital admissions. Then there will be no capacity to offer intensive care to anyone who should have it. The epidemic must therefore be fought.

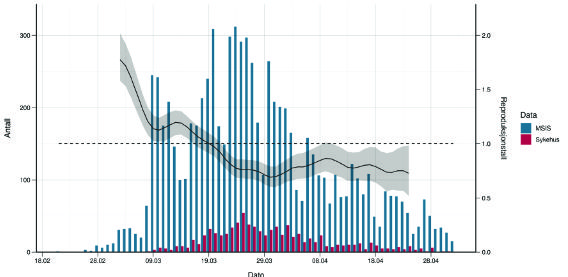

A number of infectious measures have brought the epidemic under control in Norway; it is now back. The epidemic has so far caused a low burden of disease in Norway, but the burden of measures is considerable, including both well-documented socio-economic consequences and probable public health consequences.

The epidemic rages on in the world, and the Norwegian population is not immune. It is necessary to find a viable way forward for the population, health service and society.

The likelihood of importing cases into Norway is now considered moderate. The consequences of imports into Norway are now considered moderate. The risk of imports into Norway is therefore now considered to be moderate.

The likelihood of dispersal in Norway is now considered moderate. The consequences of dispersal in Norway are now considered moderate. The risk of spreading in Norway is therefore now considered to be moderate.

The overall goal should be that the disease burden of the epidemic should remain low, the health service should not be overloaded, and adverse effects and costs of the infection prevention measures should be low. To achieve this, the strategy must be dynamic: measures must be adjusted according to the development of the epidemic and knowledge.

The core is still hygiene measures, early detection and isolation of the infected and tracking of follow-up (and quarantine) of close contacts to the infected. The travel measures and the most comprehensive (population-oriented) contact-reducing measures have adverse effects and costs, and it is hardly sustainable to maintain everyone for a very long time. We recommend a number of changes.

At the same time, we must constantly improve measures to protect the elderly, especially residents of nursing homes and care homes and recipients of home nursing care.

Furthermore, we recommend that the health service, especially the intensive care units and nursing homes, continue preparations for a high number of patients with covid-19 so that it can deal with any increase in the epidemic.

We need to have a good dialogue with the population about the epidemic’s development, strategy and measures. The population must be prepared for the epidemic to last for many years, for many to continue to be ill, but for only a few to become seriously ill. It’s several years until this epidemic is over!

The audience must understand that a zero vision is not realistic; the risk can be reduced, but not eliminated, and that voluntary support for the measures is still crucial to keeping the epidemic under control.

We propose a system to monitor the situation and adjust measures as needed.

Through our monitoring, research-based analysis and infection modeling, the Institute of Public Health will provide an approximate real-time picture of the epidemic and better knowledge of where and in which situations infection is particularly occurring.

We will also consider whether changes in measures are necessary and if so, what measures and how they should be changed. Such an assessment must take into account the combination of four factors that are interdependent: the burden of disease, capacity in the health service, the expected contagion effect of the infectious measures and the burden of infectious measures, i.e. their adverse effects.

We will warn against the automatic reintroduction of measures at certain thresholds for the epidemic indicators. There are so many factors that should be considered that it is better to have an overall assessment with an attempt to weigh the expected infectious effect of measures against expected disadvantages. Strengthening or reintroduction of measures must therefore take place following a well-founded process, with emphasis on all the four factors above.

[End of extract]

Dr Camilla Stoltenberg, Director-General of the Institute, said on 22 May that the country could have controlled the virus without lockdown. Speaking to the state broadcaster about the report, she said: ‘Our assessment now…. is that we could possibly have achieved the same effects and avoided some of the unfortunate impacts by not locking down, but by instead keeping open but with infection control measures’, because the reproduction number had fallen to 1.1 before the lockdowns were announced on 12 March. ‘The scientific backing was not good enough’, she added. It’s important to admit the truth, DG Stoltenberg said, because if the infection levels were to rise again, or a second wave hit Norway next winter, the country needed to be brutally honest about the effectiveness of lockdown.

On 27 May, PM Erna Solberg went on television to confess she had panicked at the start of the pandemic and introduced the tough measures unnecessarily. In particular, closing of schools was not just unnecessary, but counter-productive. Margrethe Greve-Isdahl is the Institute’s expert on infections in schools. She told the UK’s Sunday Telegraph that if schools had stayed open, they could have played a role in informing people in badly hit immigrant communities of hygiene and social distancing rules:

They can learn these measures in school and teach their parents and grandparents, so at least for some of these hard-to-reach minorities, there might be a positive effect from keeping kids in school… There’s now a lot of information available on how it has impacted negatively on the economy and on vulnerable children.

Political leaders and senior public health officials of other countries, including Australia, should emulate the excellent example of candour set by the Norwegians.

Ramesh Thakur

Ramesh Thakur is a professor emeritus at the Crawford School of Public Policy, the Australian National University.

This piece was originally published in Pearls and Irritations and republished here with their kind permission.

TODAY’S FEATURED BOOKS