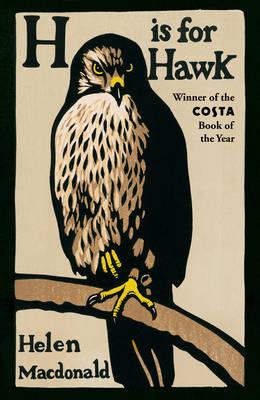

Perhaps the single most successful book of 2015, “a soaring triumph” as the critics have described it, H is for Hawke is an absolute must read. Every now and then something breaks through the zeitgeist. Author Helen MacDonald wrote in one of the opening riffs: “Forty-five minutes north-east of Cambridge is a landscape I’ve come to love very much indeed. It’s where wet fen gives way to parched sand. It’s a land of twisted pine trees, burnt-out cars, shotgun-peppered road signs and US Air Force bases. There are ghosts here: houses crumble inside numbered blocks of pine forestry. There are spaces built for air-delivered nukes inside grassy tumuli behind 12ft fences, tattoo parlours and US Air Force golf courses. In spring it’s a riot of noise: constant plane traffic, gas-guns over pea fields, woodlarks and jet engines. It’s called the Brecklands – the broken lands – and it’s where I ended up that morning, seven years ago, in early spring, on a trip I hadn’t planned at all. At five in the morning I’d been staring, sleepless, at a square of streetlight on the ceiling. Nnngh. Must get out, I thought, throwing back the covers. Out! I pulled on jeans, boots and a jumper, scalded my mouth with burnt coffee, and it was only when my frozen, ancient Volkswagen and I were halfway down the A14 that I worked out where I was going, and why. Out there, beyond the foggy windscreen and white lines, was the forest. The broken forest. That’s where I was headed. To see goshawks.”

As one of the UK’s leading newspapers The Telegraph recorded, H is for Hawke is filled with the elemental heft of hawks and the lingering bouquet of death. It opens with the sudden loss of Macdonald’s father, a successful Fleet Street photojournalist, from a heart attack. In the wake of his death, Macdonald buys a goshawk, names it Mabel and begins the slow waltz of its training.

A historian at Cambridge, MacDonald she has the countryside at her feet and the need to fill her time. Mabel, her newly acquired Goshawk, in return needs endless supplies of chick meat and a reason to trust. When the bird emerges blinking and jittery from a box on a Scottish quay, her new owner is instantly bewitched. “Two enormous eyes. My heart jumps sideways. She is a conjuring trick,” writes Macdonald. “A griffin from the pages of an illuminated bestiary.”

As Telegraph recorded: “From Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water to Richard Mabey’s Nature Cure, there is a long literary tradition of paying tribute to the curative company of animals. And Macdonald knows only too well in whose wellingtons she walks, referencing the work of Peter Matthiessen and William Fiennes among many writers who have found their way back to happiness by muddy, paw-and-claw marked paths.”

Here is a brief extract:

I knew it would be hard. Goshawks are hard. Have you ever seen a hawk catch a bird in your back garden? I’ve not, but I know it’s happened. I’ve found evidence. Out on the patio flagstones, sometimes, tiny fragments: a little, insectlike songbird leg, with a foot clenched tight where the sinews have pulled it; or – even more gruesomely – a disarticulated beak, a house-sparrow beak top, or bottom, a little conical bead of blushed gunmetal, slightly translucent, with a few faint maxillary feathers adhering to it. But maybe you have: maybe you’ve glanced out of the window and seen there, on the lawn, a bloody great hawk murdering a pigeon, and it looks the hugest, most impressive piece of wildness you’ve ever seen. It’s always a sparrowhawk, never a goshawk: goshawks resemble sparrowhawks the way leopards resemble housecats. Bigger, bulkier, bloodier, deadlier, scarier and much, much harder to see. Birds of deep woodland, not gardens, they’re the birdwatchers’ dark grail. You might spend a week in a forest full of gosses and never see one, just traces of their presence. Perhaps you’ll find a half-eaten pigeon sprawled in a burst of white feathers on the forest floor. Or you might be lucky: walking at dawn you’ll turn your head and catch a split-second glimpse of a bird hurtling past and away, huge taloned feet held loosely clenched, eyes set on a distant target. Looking for goshawks is like looking for grace: it comes, but not often, and you don’t get to say when or how. But you have a slightly better chance on still, clear mornings in early spring, because that’s when goshawks eschew their world under the trees to court each other in the open sky. That was what I was hoping to see…

It was 8.30 exactly. I was looking down at a little sprig of mahonia growing out of the turf, its oxblood leaves like buffed pigskin. I glanced up. And then I saw my goshawks. There they were. A pair, soaring above the canopy in the rapidly warming air. There was a flat, hot hand of sun on the back of my neck, but I smelt ice in my nose, seeing those goshawks soaring. I smelt ice and bracken stems and pine resin. Goshawk cocktail. They were on the soar. Goshawks in the air are a complicated grey colour. Not slate grey, nor pigeon grey. But a kind of raincloud grey, and despite their distance, I could see the big powder-puff of white undertail feathers, fanned out, with the thick, blunt tail behind it, and that superb bend and curve of the secondaries of a soaring goshawk that makes them utterly unlike sparrowhawks. These goshawks weren’t fully displaying: there was none of the skydiving I’d read about in books. But they were loving the space between each other, and carving it into all sorts of beautiful concentric chords and distances. A couple of flaps, and the male, the tiercel, would be above the female, and then he’d drift north of her, and then slip down, fast, like a knife-cut, a smooth calligraphic scrawl underneath her, and she’d dip a wing, and then they’d soar up again. They were above a stand of pines, right there. And then they were gone. One minute my pair of goshawks was describing lines from physics textbooks in the sky, and then nothing at all. I don’t remember looking down, or away. Perhaps I blinked. Perhaps it was as simple as that. And in that tiny black gap which the brain disguises they’d dived into the wood…

Hawks aren’t social animals like dogs or horses; they understand neither coercion nor punishment. The only way to tame them is through positive reinforcement with gifts of food. You want the hawk to eat the food you hold – it’s the first step in reclaiming her that will end with you being hunting partners. But the space between the fear and the food is a vast, vast gulf, and you have to cross it together. I thought, once, that you did it by being infinitely patient. But no: it is that you must become invisible. You’re trying to get her to look at the steak, not at you, because you know – though you haven’t looked – that her eyes are fixed in horror at your profile. All you can hear is the wet click, click, click of her blinking.

To cross this space between fear and food you need – very urgently – not to be there. You empty your mind and become very still. You think of exactly nothing at all. The hawk becomes a strange, hollow concept, as flat as a snapshot or a schematic drawing, but at the same time, as pertinent to your future as an angry high court judge. Your gloved fist squeezes the meat a fraction, and you feel the tiny imbalance of weight and you see out of the very corner of your vision that she’s looked down at it. And so, remaining invisible, you make the food the only thing in the room apart from the hawk; you’re not there at all. And what you hope is that she’ll start eating, and you can very, very slowly make yourself visible. Even if you don’t move a muscle, and just relax into a more normal frame of mind, the hawk knows. It’s extraordinary. It takes a long time to be yourself in the presence of a new hawk.

But I didn’t have to learn how to do this. I was already an expert. It was a trick I’d learnt early in my life; a small, slightly fearful girl, obsessed with birds, who loved to disappear. When I was a child I’d climb the hill behind my house and crawl into my favourite den under a rhododendron bush, wriggling down on my tummy under overhanging leaves like a tiny sniper. And in this secret foxhole, nose an inch from the ground, breathing crushed bracken and acid soil, I’d look down on the world below, basking in the fierce calm that comes from being invisible but seeing everything. Watching, not doing. Seeking safety in not being seen. It’s a habit you can fall into, willing yourself into invisibility. And it doesn’t serve you well in life. Believe me it doesn’t. Not with people and loves and hearts and homes and work. But for the first few days with a new hawk, making yourself disappear is the greatest skill in the world.

Read on:

Read on.