By Paige Gleeson, University of Tasmania

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison says “we shouldn’t be importing” the Black Lives Matter movement. But in the 1800s, Australia imported plantation owners from the American South.

Prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, the American south produced almost all of the world’s cotton. As war threatened, plantation owners returned to England and English cotton mills ground to a halt.

A new source of cotton was required, and Queensland would be widely promoted as a cotton growing colony and the “future cotton field of England”. The colony government invited mill and plantation owners and workers to re-migrate and re-establish their industry in Queensland.

Under 1861’s “Cotton Regulations”, individuals and companies could lease land and receive the freehold title within two years if one-tenth of the land was used for growing cotton.

As early as June of that year – barely two months after the civil war officially began – the Muir brothers, Robert, Matthew and David, established the Queensland Manchester Cotton Company and initiated plans to send an agent to Queensland to begin the process of establishing plantations.

The brothers owned cotton plantations in Louisiana before returning to Manchester and then on to Queensland. The manager of the company, Thomas William Morton, also migrated from Louisiana to Queensland via England. His son Alexander went on to become the prominent curator of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

After an agreement was made between the government and shipping companies in 1863, thousands of “cotton immigrants” travelled to Queensland, and profits of American slavery were reinvested in Queensland’s new tropical plantation economy.

A colony for cotton

Disruption of the American slave trade didn’t only lead to the search for new fertile soil. Plantation owners also wanted cheap labour for the burgeoning Australian cotton industry.

The free labour of enslaved African Americans had generated immense profits, and Australian plantation owners were unable to induce sufficient numbers of white men to labour in the tropics on low wages.

(Popular medical theories also posited the physical unsuitably of white men for work in the tropics, conveniently maintaining racial hierarchy.)

Plantation owners turned to the Pacific Islands to ensure a steady supply of indentured labour.

Read more: Was there slavery in Australia? Yes. It shouldn’t even be up for debate

Under the indenture system, workers were bound to an employer for a specified length of time. These contracts were governed by Masters and Servants Acts with conditions set steeply in favour of plantation owners.

The work was physically demanding, and rates of death and injury were high. During a Pacific Islander’s first year of indenture, the death rate was 81 per 1,000 – especially startling given labourers were in their physical prime, usually between 16 and 35 years of age.

Most cotton plantations failed by 1866 due to flooding and crop disease. Owners reinvested in sugar and the labour trade grew to meet demand.

Between 1863-1902, 62,000 Islanders migrated to Australia.

An ongoing legacy

The Queensland colonial government established a tropical plantation economy which benefited from capital, workers and working conditions imported from the American south to the sugar fields of Queensland.

Labourers’ obligations to their employers were almost unlimited, and their rights were limited to the payment of wages.

The legal conditions of indenture made a worker’s refusal to comply with duties demanded by his or her master a prosecutable offence, no matter how small (or unreasonable) the task. Planters could bring charges in local courts against workers for absconding, “malingering”, or “shirking” (deliberately working slowly) – actions sometimes employed by Islanders as forms of resistance.

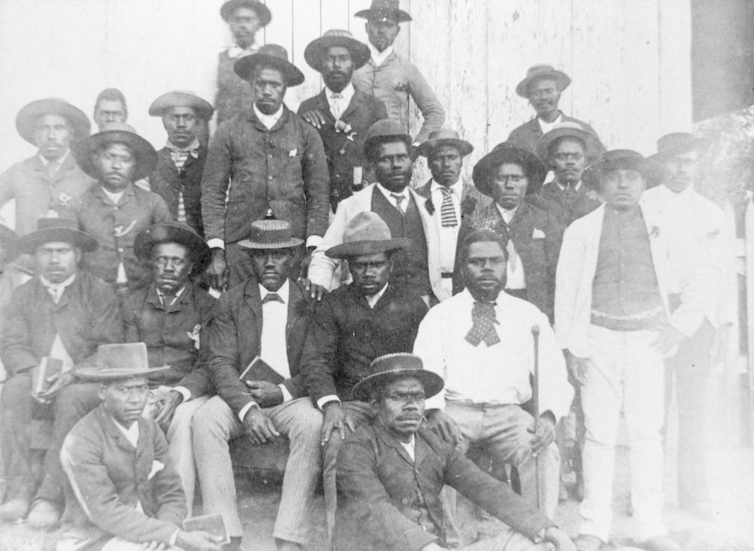

The Islander workers fought for increased rights, resisting Australian colonial society at times, while at other times adapting to it. The workers would be granted increased protections from “blackbirding” (recruiting labour via kidnapping, coercion or exploitation) under the Polynesian Labourers Act 1968, and later fought for their rights against deportation under the White Australia Policy.

Despite the harsh conditions, many South Sea Islanders returned to Queensland on multiple contracts, entering a pattern of “circular migration” from the islands of the Pacific to Queensland and back again. Others stayed on after their contracts had expired, became knowledgeable about the labour market and the value of their skills, and engaged in short term contracts on their own terms.

Many Islanders laid down permanent roots in Queensland, marrying Aboriginal and white Queenslanders, starting families and establishing homes.

These people are the ancestors of the contemporary Australia South Sea Islander community, who went on to have important roles in Australian society and advocate for recognition of their communities.

Australia doesn’t need to “import” protests against racism now: this importation happened centuries ago.

Paige Gleeson, PhD Candidate, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Feature Image: Lorne sugar plantation in Mackay, 1874. State Library Queensland.