By Frank Bongiorno, Australian National University

The late historian John Hirst liked to tell students from overseas that Australians are an obedient people. To those of us raised on the idea that we were an anti-authoritarian nation of larrikins, his suggestion seemed mischievous. Hirst explained:

The Australian people despise politicians, but the politicians can extract an amazing degree of obedience from the people, while the people themselves believe they are anti-authority.

Australians are suspicious of persons in authority, but towards impersonal authority they are very obedient.

I have often thought of Hirst’s remarks during the recent weeks of the pandemic. Opponents of the severe Victorian lockdown, contemplating polling that indicates it has broad public support, have suggested people are suffering from Stockholm syndrome – the tendency of hostages to form emotional bonds with their captors.

This seems rather unlikely. A more plausible explanation is that Hirst is right. Citizens are capable of distinguishing between their attitude to the political class, or any particular member of it, and their attitude to those in authority who are doing their best to keep them alive and well.

Hirst, of course, had no problem finding evidence for his proposition. He could cite phenomena as diverse as compulsory voting, random breath testing, bans on smoking in public places and compulsory bike helmets. Most of us only begin to recognise the peculiarity of some of these ways that governments regulate our behaviour when we are outside the country, or if we have come from somewhere else.

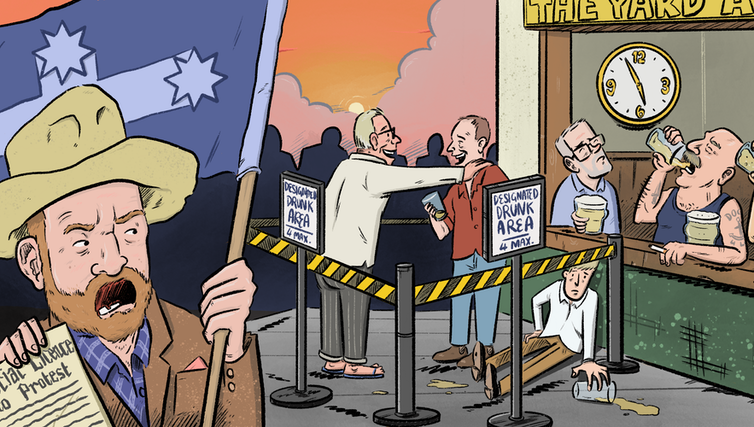

Stephen Knight, the literary academic and English migrant, found quite bizarre the intricate regulation surrounding the simple pleasure of having a drink in an Australian pub of the 1960s. Evocatively, he called one of his books Freedom Was Compulsory.

The six o’clock swill might no longer be with us, but for Melbourne residents the eight o’clock curfew – shortly to be pushed to 9 – remains. They won’t be getting a drink in a pub for love or money any time soon.

Read more: Australia’s politicians have learned that in the era of coronavirus, the future comes at you fast

And for those outside Victoria, try taking a beer out to the footpath outside your local and stand around having a yarn with your mates. See how long you last before you’re told about the licensing laws.

The reality is that most know the rules and few try flouting them. But drinking on the footpath outside a pub is taken for granted in Britain – the evidence can often be discerned outside the said pub the following morning.

Does any of this explain why, at least so far, the great uprising against “Dictator Dan” (Andrews) appears to be at a somewhat formative stage? Most Australians seem to have a utilitarian understanding of their rights.

Judith Brett, in her book From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia Got Compulsory Voting, called Australia’s political culture “majoritarian and bureaucratic”. We do not generally see our individual rights as trumping government authority. Rather, Brett suggests, our dominant way of thinking and acting owes more to the ideas of the utilitarian Jeremy Bentham: “without government and law there are no rights”.

Read more: Book extract: From secret ballot to democracy sausage

Perhaps that’s going too far: clearly, the appeal to natural rights – often expressed as human rights – has had a growing influence on our thinking since the second world war. It was there in the 1997 film The Castle, which found in Section 51 (xxxi) of the Australian Constitution support for the proposition that “a man’s home is his castle”. https://www.youtube.com/embed/Gp6f1EMn1lo?wmode=transparent&start=0

If this seemed an unlikely interpretation, it was still more plausible than the idea the Universal Declaration of Human Rights contained support for a citizen unwilling to don a mask in a Bunnings store. Rights talk is very much a part of Australian public discourse, even if it gives rise to some fairly rough and ready do-it-yourself lawyering.

Historically, Australians have sometimes appealed to their “rights” in countering government or even in justifying peaceful or armed resistance. The so-called Rum Rebellion, which led to the overthrow of Governor William Bligh by the military on January 26 1808, was influenced by the rebels’ belief that Bligh had encroached on their rights – such as their ownership of property. And some were influenced, to some extent, by the ideals associated with the American Revolution.

Similarly, the Eureka uprising on the Ballarat goldfields in 1854 was American-influenced: “no taxation without representation” was the cry of some of those resisting the government’s imposition of a licence tax on them.

Later still, when opponents of conscription during the first world war made their arguments, they often denied the authority of the government to compel individuals to fight against their will.

Some historians have speculated that if the government of the day had tried introducing conscription without a referendum, it would have met with widespread disobedience. Even if it had done so with the force of a “Yes” vote behind it, there might also have been resistance. We’ll never know, because the matter was decided in two referendum votes in 1916 and 1917.

But wartime – and especially the second world war – does provide another indication of Australians’ high tolerance for interference in their daily lives, if they are persuaded that restrictions are necessary for the common good. Rationing, the direction of labour, censorship and conscription for service in the Pacific: these were all features of Australia’s wartime experience.

So far, a majority has stood firm in Victoria as elsewhere in accepting the need for severe restrictions in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible the weeks ahead might test the limits of people’s tolerance. But we should not imagine there is likely to be any erring on the side of disobedience.

None of this means that most Victorians love Daniel Andrews. Nor does it mean they will necessarily vote for him and his party at the next election.

One reason for Australians’ obedience is their majoritarianism. They know that they will have the opportunity, sooner or later, to deliver a thumbs-up or thumbs-down in the conventional manner. At the ballot box.

Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.