The Photography of Dean Sewell/Oculi. Text by John Stapleton.

The Spinifex People, as they are now known, are the immediate descendants of the last nomadic hunter gatherers to experience contact with the modern world.

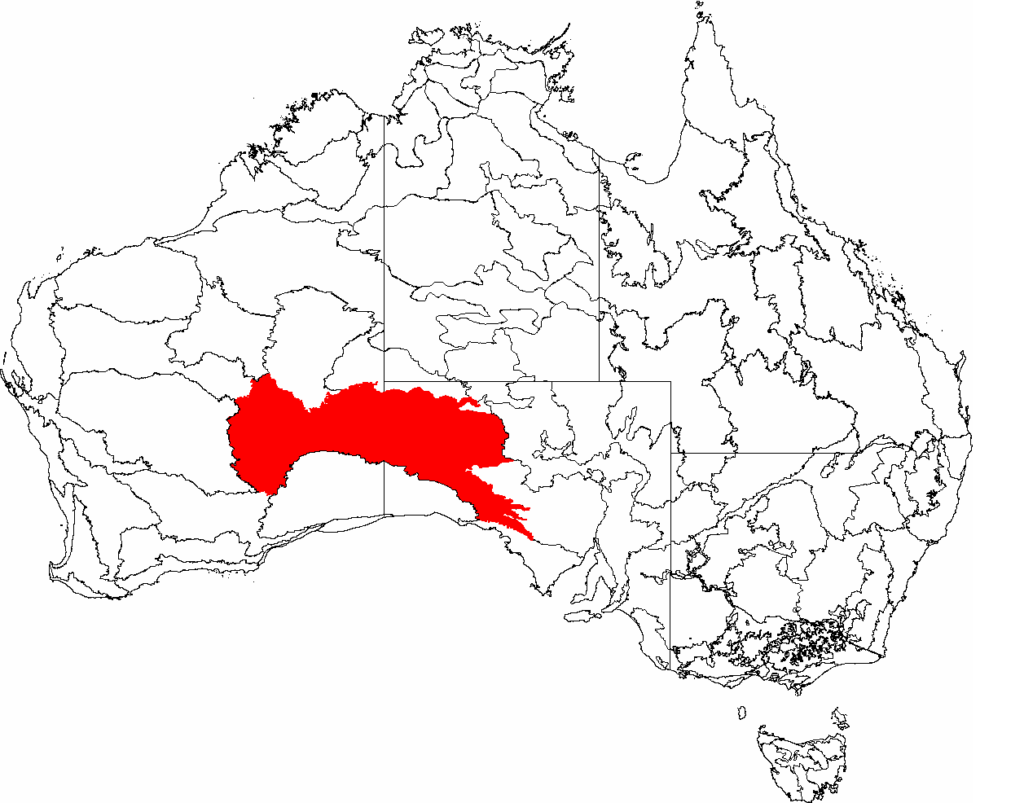

They live on the southern flank of the Great Victorian Desert.

In Australia, there are circuits for all genres of music, be it jazz, blues, rock, folk, indie, techno.

There is also a circuit for Desert Rock.

It is a parallel universe to mainstream musical circuits.

“I knew of the Desert Stars through work and the guys out of The Re-Mains, veterans of the alt-country rock scene,” records Dean Sewell, one of Australia’s most celebrated news and documentary photographers. “I had worked previously with them, journalistically, and travelled with them to Western Australia where they would team up with the Desert Stars in a joint tour of the deserts.

“The contact came about through my friendship with Leigh Ivin, the guitarist with The Re-Mains who recorded the Desert Stars studio album Mungangka Ngaranyi? It’s On Tonight? in a knocked up studio in the remote Ilkulka Roadhouse.

“The desert circuit is one of the most unique experiences in terms of rock photography. Most photographers who cover rock bands are working on tours around big cities, obsessed by superstars and stadiums.

“I had never been on a tour that took you out to these incredible deserts. The expanse of the land out there is immense, mind boggling.”

In 1984 a group called the Pintupi Nine, who were then considered the last of Australia’s indigenous people to have never had contact with the West, emerged from the desert. The Nine consisted of two sisters and their seven teenage children, all of whom shared one father. They were the only remaining nomads the government had failed to round up. Alone in the desert, they thought the planes overhead were the devil.

Eventually they made contact with their relatives near Kiwirrkurra, routinely described as the most remote community in Australia, with a settled population of just over 200. It is located in the Western Australia’s Gibson Desert, 1200 kilometres east of Port Hedland and 700 kilometres west of Alice Springs.

The news made headlines around the world.

The group had no idea what electricity was, had never seen a house, had no knowledge of modern forms of communication or technologies, and had no idea they were in a country called Australia.

As the BBC recorded: “They had been unaware of the arrival of Europeans on the continent, let alone cars or even clothes.”

They were thought to be the last family of nomads to roam the territory around Lake Mackay, a vast glistening salt lake spanning 3,500 sq km between the Gibson and Great Sandy deserts of Western Australia.

Waterholes in the area are often 40 kilometres apart or more, and every day was spent walking in the relentless heat.

As Yukultji, the youngest of the Pintupi Nine recalled years later: “When I was young I would play on the sand dune and when we saw the old people returning to camp we would go back and see what food they had brought with them. After we ate we’d go to sleep. No blanket, we would sleep on the ground. Then we would go to another waterhole and make another camp.

“Sometimes there was no water, so we would hunt for goanna.”

The blood of those monitor lizards, which they drank, ensured their survival in one of the harshest environments on Earth.

The group was frequently labelled by the international press as “The Lost Tribe” or “The Last of the Nomads”.

These were descriptions the group, when they became aware of them, found offensive. They were not lost. They were on their lands. They were exactly where the spirits intended them to be.

The world knew of the Pintupi Nine.

They never heard of the “Spinifex Seven”, truly the last peoples to emerge out of the desert.

Their exposure was limited. Lessons were learnt from the damage caused by the international exposure of the Pintupi Nine.

Rumours had always persisted that there might be others still alive out in the desert; the stories fueled by intermittent sightings of tracks and abandoned windbreaks.

In 1986 a group from Coonana, a small indigenous community 775 kilometres east of Perth, set off in vehicles for a ceremonial visit to their native lands.

They discovered fresh footprints and followed the trail for two days.

One member of the party set off on foot one morning before dawn, using a torch of burning wood to light his way.

As Professor Greg Castillo of Berkeley University, one of the few people to have looked intelligently and empathically at this extraordinary circumstance, wrote in his seminal essay Spinifex People as Cold War Moderns:

“Hours later, he sighted the family. Encamped in a wiltja, a windbreak, carrying wooden spears and implements, they were still painted with red, yellow and white ochre in preparation for the ritual reburial of a deceased relative.”

Ian Baird, a white Aboriginal Studies graduate from Adelaide who accompanied the expedition, would recall: “They spoke really quickly, like a bird twittering. When they moved it was like they were moonwalking.”

Castillo reconstructs the life of those last nomads: “The family walked from rock hole to rock hole spearing kangaroo, emu, goanna, blue-tongued lizard and mallee hen: the last of five hundred generations to pursue this nomadic way of life across a stretch of remote country now stripped of all other residents.

“Seeing the glint and streaks of aircraft in desert sky, they threw magical objects at them and sang protective songs.

“White people were ghosts traveling above them and across the land. They found clothes and pieces of metal left behind by desert visitors, studied tire track imprints, and carefully obscured their own tracks to avoid detection.

“The couple told their children that distant trains were roaring Wati Wanampi, venomous water-snake beings.”

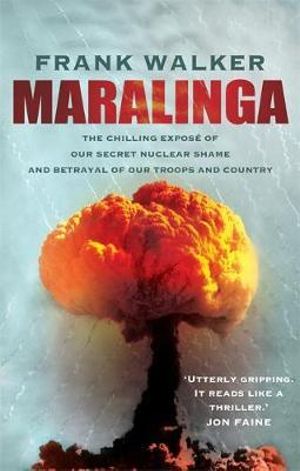

What makes the story of the Spinifex people even more compelling was that they had been on the edge of, and experienced, one of the most powerful conflagrations Western civilisation had ever devised, the testing of nuclear weapons at Maralinga.

Recollections of those devastating explosions, from which some of their elders had dug holes and covered themselves in the sand to avoid, can be heard in the songs of the Desert Stars to this day.

I thought I heard a thunder near Maralinga

I thought I seen a serpent man

Rising up in black and white

I feel fear in the air

Feel my spirit running.

Yeh, I’m running ‘cos I heard it explode

Yeh, I been running.

I had to get away from the serpentine place

To warn all my people

I been running in fear

Running across the desert to survive.

Running. Desert Stars.

Maralinga, the site of British nuclear testing, is one of the greatest scandals of modern Australian history, perhaps little known outside the country. It was at Maralinga that the British conducted atomic testing between 1956 and 1963.

The site, nearby the sacred, stunningly beautiful Pitjantjatjara Lands in Central Australia, was cleared of the indigenous people prior to the testing beginning.

The Pitjantjatjara Lands border the Great Victoria Desert.

Military testing began before all the nomads had been rounded up. It was not generally believed that humans could survive in this environment.

The Spinifex People, tired of a sedentary lifestyle, began moving out of Cundeelee Mission and established their own settlement at Tjuntjuntjara.

“These guys are pretty wild dudes,” recalls Dean of his first encounter with the Desert Stars on their own lands. “Being indigenous, they are in and out of prison every six months or so. Mostly petty shit. Driving without a licence, unregistered vehicles. They exist between Tjuntjuntjara and the gold rush town of Kalgoorlie several hundred kilometres south-east.

“They hurtle through the desert in these barely road-worthy vehicles. By the time they get to Kalgoorlie the cops pick them up. They get caught in a legal cycle of being in and out of prison. There is nothing more cruel than to place a nomadic person inside a jail cell, in their own country.”

Yeh, it’s blazing red flashing blue

White blue stripes coming down the road

But I ain’t going to let them take me down

Yeh I ain’t going to let them take me down.

Blazing red, flashing blue lights

Here they come

Blazing red, flashing blue lights

Here they come.

I’m on my way to gravel road.

I hit the open road heading back home

I push the pedal to the metal

A high speed chase

Here they come flashing their red blue lights

I’m on my way to the gravel road

Catch me if you can.

Gravel Road. Desert Roads.

Dean Sewell witnessed many escapades. He recalls, “Desert driving is a whole different discipline, and they’ve mastered it without the aid of four-wheel drive technology.

“They figure if they can just get off the bitumen, they can out drive any copper.

“Derek Coleman, lead guitar and backing vocalist, managed to get a lowered Mitsubishi sedan across 50 kilometres of sand dunes to make it on time for the tour.

“Us whities managed to bog a Toyota LandCruiser on the same dunes.”

Dean Sewell recalls that the only time the Desert Stars spoke English was when they were in the company of ‘whities’.

“They speak their original language. They’re not urbanised. Their lifestyle is traditional, except they now have guns to shoot kangaroos.”

As Mick Daley, frontman for The Re-Mains, wrote: “It’s exhilarating stuff, hunting with the wardens of their ancient country.

“They inhabit a richly textured tapestry of music and art that invokes scientific principles of ecology, astronomy and quantum physics and are direct descendants of people who thought nothing of walking naked through stony desert without water, carrying possessions, babies and immense libraries of oral knowledge, with ancestral songs providing navigational maps.

“They abide strictly by ancient laws more stern than any Biblical proscription yet their music and art is as vital as any and they survived the British Empire, nuclear holocaust, smallpox and generational kidnapping.”

These are not urban people. The way they interact bears no resemblance to the way people behave in a metropolis.

“When I first met them they came across as timid, almost shy. In a city you launch into a conversation with anybody. In company, in contrast, they are reserved.

“They were quite set back by the use of our foul urban tongue. Being a bunch of journalists and musicians, we do have a blunt style of communication.

“Because they talk in tongue, they don’t use the expletives we use in common talk. When they talk in English, not every second word is a swearword. They’re polite.”

“On my first meeting with the Spinifex people in their own lands, we were taken out onto their country. They were very hospitable. They showed us significant places around Tjuntjuntjara.

“These people were the next generation on from the Spinifex Seven. Some of the original Seven still live in the community to this day.”

Jay Minning, lead vocalist and guitarist with the Desert Stars, grew up in both Cundalee and on land and was introduced to AC-DC that the older generation would bring back from their visits to Kalgoorlie, where they would be doing everything from seeing family to going on drinking bouts in the pubs.

That early AC-DC sound reverberates through their music, to the extent that they have been nicknamed “Blackadacca”.

Kalgoorlie is the most important social hub for the indigenous people living in gold field country, and across the Gibson and Great Victoria deserts.

“They would bring back cassette tapes from those visits.

“Jay’s early experiences of music was from those cassettes; and he would play drums on old tin cans. His first guitar was made out of found objects.”

We did a three week tour covering 15,000 kilometres.

Rhythm guitarist, Derek, was still driving around Tjuntjuntjara as we were about to leave. He’s a diabetic and he jumped on the bus without a change of clothes or his medication.

And thus began one of the most extraordinary experiences of my life, rock music as nobody has ever seen it before.

The first official tour gig was held in their own community of Tjuntjuntjara to acquaint the community with The Re-Mains and to test out the hired gear they had picked up on their arrival in Perth.

From there we headed north to Warburton, an indigenous community just south of the Gibson Desert. It took us two days to do the 1500 kilometre slog through a very precarious track. Some of it is corrugated gibber desert road, and takes a toll on the vehicles, not to mention the people.

“It was a really hard trip,” recalls Dean. “We had this eight tonne desert faring vehicle with a high centre of gravity. Fully loaded it was probably in excess of ten tonnes.

“For the uninitiated, the Warburton Roadhouse where we stayed is like the Green Zone in Baghdad. It is fortified in steel and concrete and wrapped in razor wire. Seemingly impenetrable.

“But we still got robbed.

“The 7-year-olds are like little jihadis. Nothing will stop them.

“They only see rich white folk, usually retired, the grey nomads as they are called in Australia, touring through the desert. The Warburton Roadhouse is a refuge for them to park their decked-out $200,000 Winnebagos. So the local youth have no compunction whatsoever in ripping them off.”

As Sewell recalls, mainstream music tours normally involve weeks or months of publicity. But out here the bush telegraph is still alive.

We arrived in Warburton, having left the Desert Stars with the responsibility of publicising this up and coming tour, but nobody had bothered to send out a flyer. Nobody knew we were coming.

But the day after our arrival, the band started bumping the equipment onto a concrete stage on the local football oval and curiosity about this unannounced event took hold. Local cars began to survey the activity, and by dusk most of the community had already assembled. Events like this will draw basically the entire population of these remote communities.

It wasn’t long after the music began that the locals, in their excitement, began igniting tufts of Spinifex grass. It looked like we were in the Pacific rim of fire. All around us the land was alight.

You see all sorts of stuff out there which bears no relationship to city life. And certainly no relationship to the ideas of all the tertiary educated do-gooders and forelock-tuggers who infest the nation’s bureaucracies.

As Nicolas Rothwell, one of Australia’s preemeninet writers on the nation’s interior, has written: “For outsiders in the bush do not, on the whole, think magically, or see the ceremonial logic of that world and the compelling force it exerts upon those plunged within it.

“The ideas western observers apply to the Aboriginal realm come, rather, from social science and cultural frameworks. They are the ideas of the Bohemian, the intellectual, the aid worker or the enlightened functionary, and they bring confusion in their wake . . . an administrative order, elaborate, with constantly shifting priorities.”

A greater problem, after that first performance in Warburton, was the discovery the following day that the tour vehicle had lost its brakes. This threatened to derail the entire tour.

The Re-Mains, versed in the art of long haul remote touring, had decided the best plan would be to continue the vehicle on to Laverton in the gold fields of Western Australia, where they would dump all the equipment.

It was a 550 kilometre stretch, but who needs brakes?

Daley and Grant Bedford, the band’s drummer, would backtrack to Kalgoorlie, where a replacement vehicle would be sourced. At this point, things were very terse. The window of opportunity to keep the tour on track was evaporating.

The Re-Mains boys arrived back in Laverton at 9pm. The vehicle was loaded and the decision was made to push through the night on route to Broome, a former pearl diving centre now tourist mecca more than 1600ks north of the state’s capital, Perth.

Being their first major tour, the Desert Stars were not accustomed to the long hours and the constant travel. Fatigue was already starting to present itself.

This was the experience The Re-Mains brought to the table. Having toured extensively through Australia’s Top End and three previous tours of Canada, in 2006 they experienced first hand the pitfalls of long haul remote touring when on one night they would have a major collision just north of Tennant Creek with a steer.

Unable to deviate without derailing their heavily laden van and trailer they had a head-on collision, resulting in the steer coming through the cabin and seriously injuring drummer Grant Bedford. Those injuries still plague him to this day.

On arrival in Broome the first order of business was to get Derek Coleman, who had walked on the bus with just the clothes he was wearing, a new set of threads.

From Broome we went south to Roebourne, a coastal town which was integral to the entire Deaths in Custody movement in Australia.

It is a heavy place

The death of John Pat, 16, in 1983 in the Roeburn prison would ignite outrage, becoming a symbol of injustice and oppression at the hands of WA police violence and ultimately lead to the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1991. Even in July of this year there was another indigenous death in Roeburn, when a 47-year-old man was found dead in his cell.

Truth be told, it was an uneventful event, with barely 20 people showing up for the concert. Once again, pre-publicity was entirely lacking and few even knew the tour was coming to their community. The place was a ghost town . town, Most of the locals were off fishing. The only audience, really, were community administrative staff.

We played at the community centre and camped nearby.

The next port of call was Marble Bar, Australia’s hottest town. Forty degrees is considered a mild day. Dean recalls: “From memory, something went awry, mostly with Jay Minning, our lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist. We arrived late in the afternoon, and left early in the morning. But things were definitely awry.”

Next stop Wiluna. This small community is on the edge of the Western Desert, at the gateway to the famous Canning Stock Route and the Gun Barrel Highway.

Three different tribal and language groups from the Maralinga nuclear testing zone were forced to live together at the Wiluna Mission.

As Sewell recalls: “It was the first destination on the tour that we would witness flyers for the coming event. In most of these remote communities the only venues that can hold such events are generally the cultural centres.”

up, each last scintilla; to go down into the darkness where they are disseminated,

down into the furthest reaches of the world, and there embrace sin and falsity. Such

paradoxes had a natural appeal, in a time when the adherents of the faith were

constantly persecuted; when established rituals brought nothing; when God’s

protection had so manifestly failed. It was this climate of ideas that paved the way

for the religious cataclysms ahead.” Nicolas Rothwell.

There’s nothing much at Menzies, our next stop, apart from a few historical buildings and surrounding ghost towns dating from the mining boom which began in the late 1800s.

The only aspect of the town which makes it of any interest to international visitors is a 2003 installation featuring 51 other-worldy figures by esteemed English sculptor Antony Gormley on the salt pans of Lake Ballard.

“Most of the black fellas I was with had absolutely no interest in a cultural oddity which attracted visitors from all around the world, but I had to go and have a look. All the Re-Mains stars came out with me, but the Desert Stars just hung out in town.”

The final stop, the Kalgoorlie Boulder Town Hall

By the end of the tour, it had all taken its toll. The normal tensions you would expect between close touring band members. The Desert Stars were weary and homesick, and buoyed by the fact they were coming back to familiar territory. Their hardcore base is located in Kalgoorlie.

At first there was talk about whether there should be a cover charge for this gig. This was the end of the tour, this was their hardcore base, and their fans were out in force. But their fans have no money.

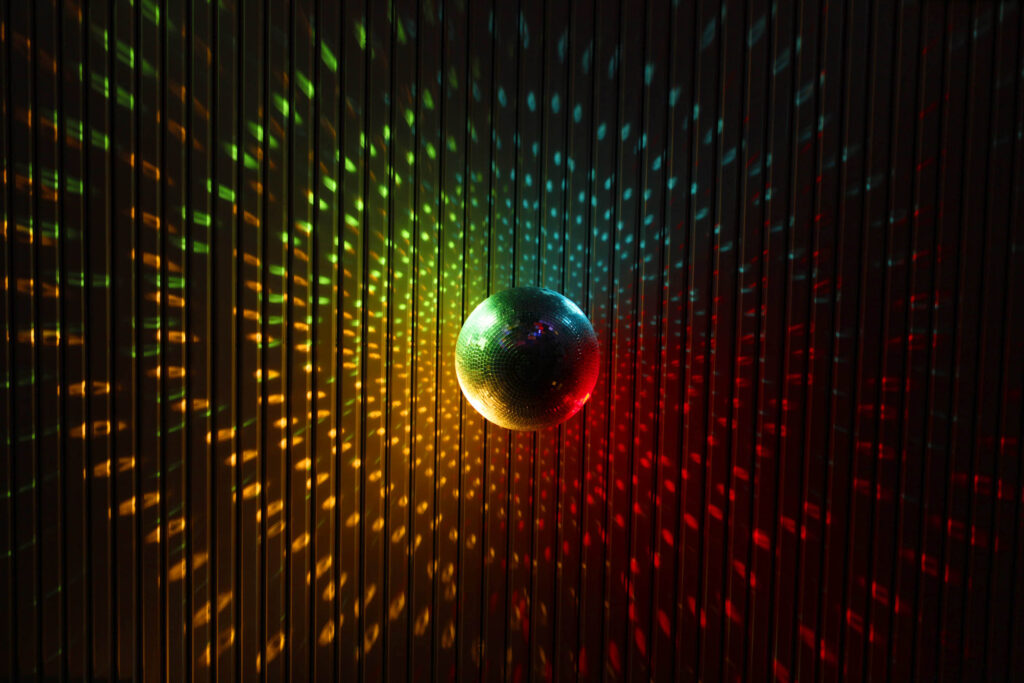

It was decided to drop the cover charge in fear of a riot on the streets. As it turned out, the elation, everybody going off, it was riotous inside.

One pair of ‘whities’ showed up, to see the Re-Mains, the rest were there for the Desert Stars, in this majestic old building. The beautifully preserved Boulder Town Hall was built in 1908 and demonstrates the architectural style of the prosperous gold rush days, and had seen the likes of opera singers Dame Nelly Melba and Joan Sutherland.

And now the Desert Stars.

What was notable, not only at Boulder but through the whole string of concerts, was the women there. They really loved rock’n’roll. They moved so well, and without artifice. Entirely unlike city nightclubs full of poseurs, charlatans and coke-heads, they were there purely to have a good time.

Multi-award winning Australian photographer Dean Sewell made his name as a news photographer and photo-journalist. Collaborations between A Sense of Place Magazine and Dean Sewell can be found here.

This piece was written and compiled by veteran Australian journalist John Stapleton, editor of A Sense of Place Magazine. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.

July 21, 2021 at 1:06 pm

Brilliant!

July 25, 2021 at 9:09 am

Absolutely brilliant article. Proper Palya!

November 26, 2021 at 11:23 am

What an incredible insight into this place, band and music. It was an eye opener. Thanks for the story.