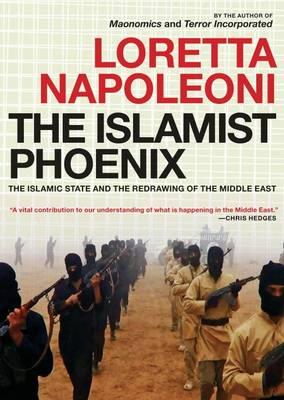

From its birth in the late 1990s as the jihadist dream of terrorist leader Abu Musab al Zarqawi, the Islamic State has grown into a massive enterprise, redrawing national borders across the Middle East and subjecting an area larger than the United Kingdom to its own vicious brand of Sharia law. This is not another terrorist network but a formidable enemy in tune with the new modernity of the current world disorder. One of the world’s leading experts on terror financing Loretta Napoleoni argues that Ignoring these facts is more than misleading and superficial, it is dangerous. ‘Know your enemy’ remains the most important adage in the fight against terrorism. Here is a book extract.

EXTRACT FROM THE ISLAMIST PHOENIX

During the last three years, the Islamic State’s successes have been unprecedented. By brutal means and steely insight it may achieve the historically unachievable: the reconstruction of a Caliphate. In the post–World War II period, no armed group has ever carved out such a large territory. At its height, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), by far the largest armed organization in the Middle East, controlled only a fraction of the land that the Islamic State rules today.

This accomplishment is often attributed to the Syrian conflict, which is seen as the incubator of a new breed of terrorism. Indeed, in the throes of a post-Arab Spring civil war, and rife with its own insurgent Islamists, Syria provides a convenient narrative to foreclose any thought of a common thread linking the Islamic State to 9/11 and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. The West and the world desperately cling to the idea that the horrifying present of Iraq and Syria has no historical precedent, that we are not responsible for current events in the Middle East. Hence, in contrast with the rugged forces of Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan or the suicide army of Al-Zarqawi in Iraq, the Islamic State is depicted as a new species: an organization able to generate vast income, acting as a multinational of violence, commanding a large and modern army, and bankrolling fully trained soldiers.

All this is true. What is not is the novelty and uniqueness of its genetic traits.

Certainly, unlike the Taliban or Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State manages vast revenues, generated in part through the annexation of productive assets, such as oil fields and electrical power stations across Syria. According to The Wall Street Journal, the export of oil alone generates $2-million per day. In addition, inside the territory it controls, it levies taxes on businesses as well as on sales of arms, other military equipment, and general goods, most of them in transit across lucrative smuggling routes along Syria’s borders with Turkey and Iraq.

If its economic and military prowess has not distinguished it as a new breed of terrorism, neither has its penchant for pre-modern displays of barbarous violence, which Western media have incorrectly reported as a shock even to the leadership of Al-Qaeda. It was Al-Qaeda itself whose infamous 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was responsible for the 2002 beheading of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, an act which, for the first time, broadcast to the world this type of barbaric murder. Pearl’s execution was followed, in 2004, by the beheading of American radio-tower repairman Nicholas Berg at the hands of Abu Musab al Zarqawi’s group. The same year, the ambush of four Blackwater contractors, whose burning bodies were dragged through the street of Fallujah, represented what many had thought was the nadir of evil. Sadly, the violent acts of the Islamic State are not without equal.

From the ashes of the War on Terror, therefore, in a post–Cold War proxy environment, the Islamic State

has repackaged itself not as a new breed of terrorism but as a mutation of its former self. Its success springs from the convergence of several factors, among which are a globalized multipolar world, a command of modern technology, a pragmatic attempt at nation-building, a deep understanding of the psychology of Middle Eastern and Muslim emigrants, and the long shadow of the West’s response to 9/11, which has plunged parts of the Middle East into a decade of sectarian warfare. Ignoring these facts is more than misleading and superficial, it is dangerous. “Know your enemy” remains the most important adage in the fight against terrorism.

The success of the Islamic State forces us to a moment of reckoning. It is time to declare the failure of counter-terrorism to prevent the advent of the Caliphate, and it is time to face our responsibilities. The world is in need of a new approach to stopping this hostile political entity, especially now as it redraws, in blood, the borders of the Middle East. Such a strategy cannot be produced by denying the obvious fact that the genesis of the Caliphate is deeply intertwined with decades of Western politics and interventions in the Middle East.

If the Islamic State succeeds in building one nation across Iraq and Syria, the threat posed by this achievement will go well beyond the political landscape of these two nations. For the first time in modern history, an armed organization will have fulfilled the final goal of terrorism: to create its own state on the ashes of existing nations, not through a revolution, as happened in Iran, but through a traditional war of conquest based upon terrorist tactics. If it does so, the Islamic State will have become the new model of terrorism.

How did we get to this point? The long answer must be sought in the partitioning of the Middle East at the hands of the former colonial powers. The short answer is found in the confluence of the preventive strike in Iraq and the civil war in Syria. The former created one of modern jihad’s most brilliant and enigmatic strategists, the late Abu Musab Zarqawi, a man who openly challenged the historical leadership of Al-Qaeda and who reignited the ancient and bloody conflict between Sunnis and Shiites as a key tactic for the rebirth of the Caliphate. Syria provided a unique opportunity, a launch pad, for those who had assimilated Al-Zarqawi’s message and who wished to achieve his dream, among them Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, the new Caliph.