John Woinarski, Charles Darwin University.

In a new series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

Books have been good to me: they have nurtured me, inspired me, taught me about life, helped me when the world seems hard. I love Russian poetry; there are shelves of fiction I enjoy. But here I want to tell of the books that helped shape my thinking about the natural environment.

There were of course many identification (field) guides that gave me the foundational knowledge of the names of plants and animals – the cast of nature. In my boyhood, these were pretty primitive, but indispensable. Guides now are far flasher. They also enticed me to seek the species shown in these books I hadn’t yet encountered, an eternal quest.

But field guides are prosaic fare. I yearned also to understand the environment, to “see” country. I was, and still am, fascinated with the puzzle of it all – how the components of nature fit together, and how the whole functions.

A few books I came across in my youth were revelatory. In Barbara York Main’s Between Wodjil and Tor (1967), the country of south-western Australia comes alive, its nature exquisitely observed, the stories and marvels of its small things – so many spiders leading such strange lives – intricately linked with a broader narrative of the workings of the landscape.

J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine (1967) provides an astonishingly acute reading of nature: the author obsessed with, almost becoming, the birds he stalks – he has succeeded in seeing the world as another species does, privileging his reader to do so also. And the verve of the writing! “We are the killers. We stink of death. We carry it with us. It sticks to us like frost. We cannot tear it away”.

I liked Graham Pizzey’s A Time to Look (1958) for its gentle evocation and appreciation of the wonder of Australian nature and its caring portraits of the lives of birds. In Nightwatchmen of Bush and Plain (1972) David Fleay is a detective, unlocking the dark mystery of owls; almost a lover in the intimacy of his connection with them.

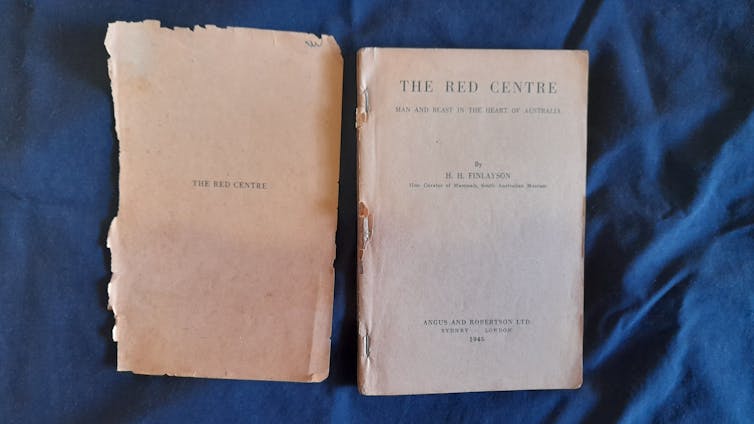

But the most formative book for me was H.H. Finlayson’s 1935 classic The Red Centre. His biography is called A Truly Remarkable Man, and it is a fitting title.

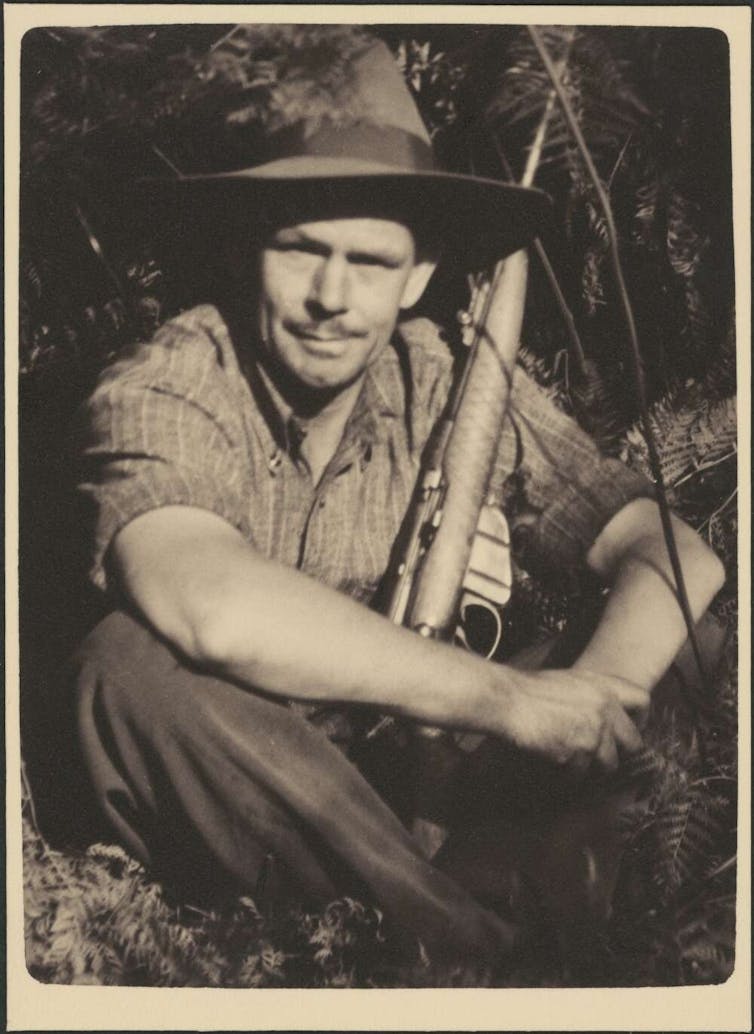

Finlayson (1895-1991) lived a life of challenges. Experimenting with explosives at 15 (as one does), he blew off parts of most fingers on his left hand. Evidently unwisely, he persisted on this course and two years later another explosion resulted in the loss of what remained of his left hand, much of his right thumb and the sight in one eye.

A brilliant, perceptive observer

Resolute and resourceful, he spent much of his life, often solitarily, studying wildlife across remote Australia. From the 1920s to the 1950s, these expeditions spanned the cusp of the devastation of the Australian mammal fauna.

Finlayson was the last to collect and record many of these mammal species: he witnessed this loss. But in his many scientific papers, and in The Red Centre, he also foretold it, explained it and mourned it.

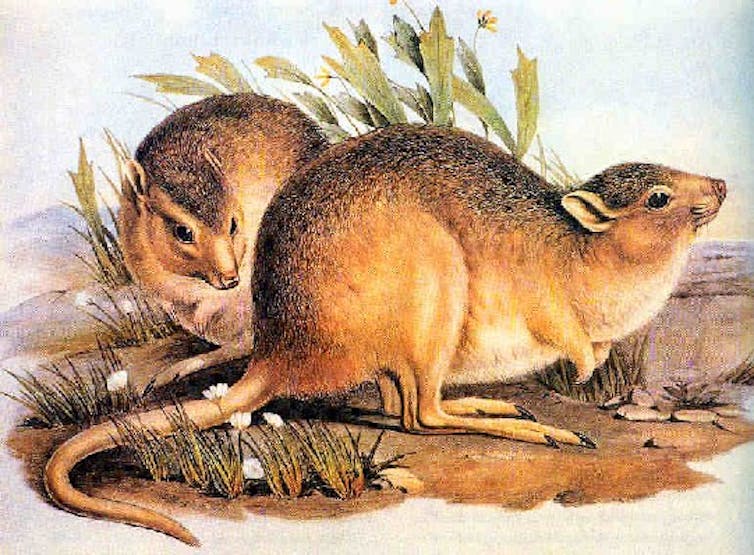

Species that are now extinct, such as the Desert rat-kangaroo and Toolache wallaby, come alive in Finlayson’s words. For several species, his notes are all that has been – will ever be – reported of their ecology.

He was a brilliant and perceptive observer, and could portray the form, the behaviour, the fit of an animal to its environment. I can see them still from his words.

And he wrote beautifully. Musing in The Red Centre on the losses:

It is not so much, however, that species are exterminated by the introduction of stock, though this has happened often enough, but the complex equilibrium which governs long-established floras and faunas is drastically disturbed or even demolished altogether. Some forms are favoured at the expense of others; habits are altered; distribution is modified, and much evidence of the past history of the life of the country slips suddenly into obscurity … The old Australia is passing.

The environment which moulded the most remarkable fauna in the world is beset on all sides by influences which are reducing it to a medley of semi-artificial environments, in which the original plan is lost and the final outcome of which no man may predict.

From more than 80 years ago, these words still haunt; and they still describe the ongoing loss of Australian nature – due to what we have done to this country.

Finlayson’s ecological understanding was profound. He could read the landscape. He gifts this understanding to the reader of The Red Centre.

Much of my career as an ecologist has been inspired by, and attempts to follow, Finlayson’s capability to see and feel country; and to better appreciate what we may lose, and how imminent such losses can be.

Of course, the ecological perceptiveness displayed in The Red Centre and Finlayson’s scientific papers owes much to his long association with and respect for the Indigenous people. Finlayson understood the connections of Indigenous people with country, and in The Red Centre often reveres and celebrates that knowledge and culture.

A present to me from a friend long ago, my copy of The Red Centre is older than me, mostly broken (it has lost its cover), much read. It is worth nothing; it is priceless.

It is a classic of Australian writing on the environment, an exquisite and poignant account of a now-lost nature, an enduring blueprint for understanding our country. I owe a lot to it.

John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.