By Jacinta Delhaize, University of Cape Town

Two giant radio galaxies have been discovered with South Africa’s powerful MeerKAT telescope, located in the Karoo region, a semi-arid area in the south west of the country. Radio galaxies get their name from the fact that they release huge beams, or ‘jets’, of radio light. These happen through the interaction between charged particles and strong magnetic fields related to supermassive black holes at the galaxies’ hearts.

These giant galaxies are much bigger than most of the others in the Universe and are thought to be quite rare. Although millions of radio galaxies are known to exist, only around 800 giants have been found. This population of galaxies was previously hidden from us by radio telescopes’ limitations. But the MeerKAT has allowed new discoveries because it can detect faint, diffuse light which previous telescopes were unable to do.

Our discovery, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, gives astronomers further clues about how galaxies have changed and evolved throughout cosmic history. It’s also a way to understand how galaxies may continue to change and evolve – and even to work out how old radio galaxies can get.

How we discovered two new giant radio galaxies. The Conversation Africa – Pasha, CC BY-NC-ND7.23 MB (download)

The giant radio galaxies were spotted in new radio maps of the sky created by one of the most advanced surveys of distant galaxies. The team working on it has included astronomers from around the world including South Africa, the UK, Italy and Australia. Called the International Gigahertz Tiered Extragalactic Exploration (MIGHTEE) survey, it involves data collected by South Africa’s impressive MeerKAT radio telescope. MeerKAT consists of 64 antennae and dishes, and started collecting science data in early 2018. It will ultimately be incorporated into the Square Kilometre Array, an intergovernmental radio telescope project spearheaded by Australia and South Africa.

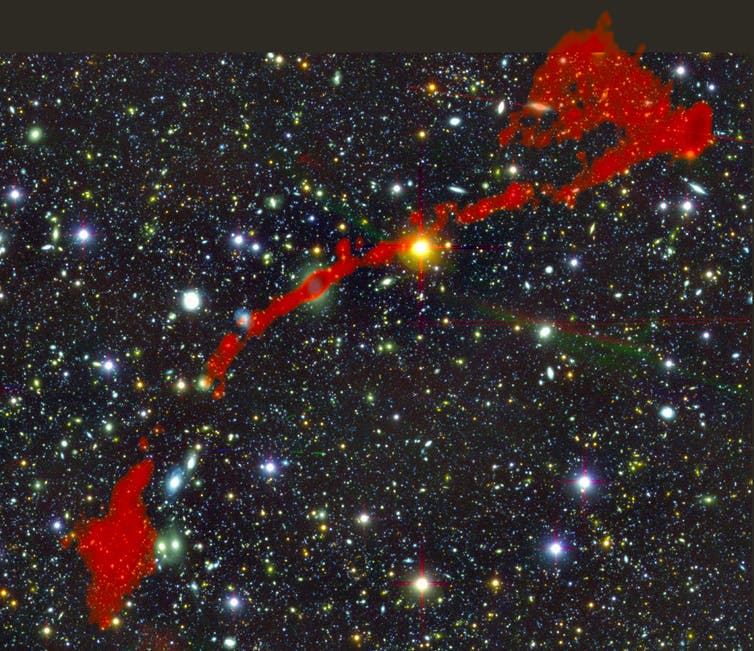

The galaxies in question are several billion light years away. The discovery of enormous jets and lobes in the MIGHTEE map allowed us to confidently identify the objects as giant radio galaxies.

Their discovery means that a clearer understanding of the evolutionary pathways of galaxies is beginning to emerge. This is tantalising evidence that a large population of faint, very extended giant radio galaxies may exist. This may help us understand how radio galaxies become so huge and what sort of havoc supermassive black holes can wreak on their galaxies.

What’s new

Many galaxies have supermassive black holes in their midst. When large amounts of interstellar gas start to orbit and fall in towards the black hole, the black hole becomes ‘active’: huge amounts of energy are released from this region of the galaxy.

In some active galaxies, charged particles interact with the strong magnetic fields near the black hole and release huge beams, or ‘jets’, of radio light. The radio jets of these so-called ‘radio galaxies’ can be many times larger than the galaxy itself and can extend vast distances into intergalactic space. Think of them like jets of water from a whale’s blowhole, a thin column extending into a cloudy plume at the end.

We found these giant radio galaxies in a region of sky that’s about four times the area of the full Moon. Based on what we currently know about the density of giant radio galaxies in the sky, the probability of finding two of them in a region this size is extremely small – only 0.0003%. So, it’s possible that giant radio galaxies – those that emit the beams, or jets of light described above – may actually be more common than we previously thought.

These aren’t the first radio galaxies astronomers have discovered. Many hundreds of thousands have already been identified. But only around 800 have radio jets bigger than 700 kilo-parsecs in size, or around 22 times the size of the Milky Way. These truly enormous systems are called ‘giant radio galaxies’.

Our new discoveries are more than 2 Mega-parsecs across: about 6.5 million light years or about 62 times the size of the Milky Way. Yet they are fainter than others of the same size. That’s what makes them harder to see.

Clues

We suspect that many more galaxies like these should exist, because of the way we think galaxies should grow and change over their lifetimes. And that’s one question we hope this discovery can help to answer: how old are giant radio galaxies and how did they get so enormous?

Now, telescope technology is making it possible to put these and other theories to the test. MeerKAT is the best of its kind in the world because of the telescope’s unprecedented sensitivity to faint and diffuse radio light. This capability is what made it possible for us to detect the giant radio galaxies. We could see features that haven’t been noticed before: large-scale radio jets coming from the central galaxies, as well as fuzzy cloud-like lobes at the end of the jets.

The fact that only very few radio galaxies are so gigantic has always been a bit of a mystery. It is thought that the giants are the oldest radio galaxies, which have existed for long enough (several hundred million years) for their radio jets to grow outwards to these enormous sizes. If this is true, then many more giant radio galaxies should exist than are currently known. And that’s important because radio jets can influence the star formation of their host galaxy. Essentially, they might ‘kill’ their galaxy by blowing out all the gas and preventing the formation of new stars.

Read more: Radio galaxies: the mysterious, secretive “beasts” of the Universe

The MIGHTEE survey continues, and we hope to uncover more of these giant galaxies as it progresses. We also expect to find many more with the Square Kilometre Array: construction of this transcontinental telescope is due to start in South Africa and Australia in 2021 and continue until 2027. Science commissioning observations could begin as early as 2023.

The Square Kilometre Array is also expected to reveal larger populations of radio galaxies, revolutionising our understanding of galaxy evolution.

Jacinta Delhaize, SARAO Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.