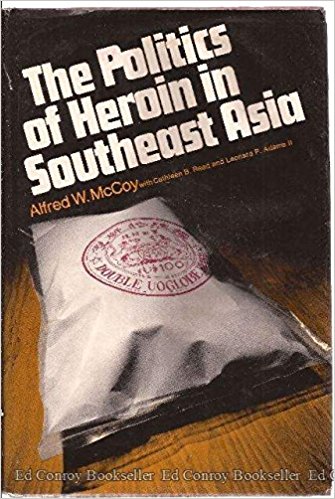

The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia, first published in 1972, was a landmark book on the heroin trade, and easily one of the most insightful books ever written on the subject. Dr Alfred McCoy is revered by journalists and fellow researchers alike, and continues to write superbly on the difficult subject of the heroin trade.

His first book on the subject was followed by The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade. Here the world’s foremost expert on the subject explains how heroin is behind the multi-faceted disaster which is the war in Afghanistan.

After fighting the longest war in its history, the US stands at the brink of defeat in Afghanistan. How could this be possible? How could the world’s sole superpower have battled continuously for more than 16 years – deploying more than 100,000 troops at the conflict’s peak, sacrificing the lives of nearly 2,300 soldiers, spending more than $1tn (£740bn) on its military operations, lavishing a record $100bn more on “nation-building”, helping fund and train an army of 350,000 Afghan allies – and still not be able to pacify one of the world’s most impoverished nations? So dismal is the prospect of stability in Afghanistan that, in 2016, the Obama White House cancelled a planned withdrawal of its forces, ordering more than 8,000 troops to remain in the country indefinitely.

It was during the cold war that the US first intervened in Afghanistan, backing Muslim militants who were fighting to expel the Soviet Red Army. In December 1979, the Soviets occupied Kabul in order to shore up their failing client regime; Washington, still wounded by the fall of Saigon four years earlier, decided to give Moscow its “own Vietnam” by backing the Islamic resistance. For the next 10 years, the CIA would provide the mujahideen guerrillas with an estimated $3bn in arms. These funds, along with an expanding opium harvest, would sustain the Afghan resistance for the decade it would take to force a Soviet withdrawal. One reason the US strategy succeeded was that the surrogate war launched by the CIA did not disrupt the way its Afghan allies used the country’s swelling drug traffic to sustain their decade-long struggle.

Despite almost continuous combat since the invasion of October 2001, pacification efforts have failed to curtail the Taliban insurgency, largely because the US simply could not control the swelling surplus from the country’s heroin trade. Its opium production surged from around 180 tonnes in 2001 to more than 3,000 tonnes a year after the invasion, and to more than 8,000 by 2007. Every spring, the opium harvest fills the Taliban’s coffers once again, funding wages for a new crop of guerrilla fighters.

At each stage in its tragic, tumultuous history over the past 40 years – the covert war of the 1980s, the civil war of the 90s and its post-2001 occupation – opium has played a central role in shaping the country’s destiny. In one of history’s bitter ironies, Afghanistan’s unique ecology converged with American military technology to transform this remote, landlocked nation into the world’s first true narco-state – a country where illicit drugs dominate the economy, define political choices and determine the fate of foreign interventions.