By Lucy Sussex, La Trobe University

“The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there,” wrote English author L.P. Hartley in The Go-Between (1953). Modern Melburnians may feel the same. But while they live with an increasing cityscape of skyscrapers, the past is not far away.

Consider Scots Church in Collins Street. Its spire tip was for some time the highest point in the city, but now it is relatively low compared to surrounding buildings. The idea behind its vantage was different to modern planning decisions: it indicated the Presbyterians had a closeness to Heaven not possessed by other Christian denominations.

Certainly, the beliefs of many 19th-century Melburnians appear equally odd. The pseudoscience of Phrenology held that the shape of people’s skulls denoted their character. Phrenologist Philemon Sohier was even allowed to take plaster casts from the heads of freshly hanged criminals. His wife Ellen, an Antipodean Tussaud, then used the casts to create realistic replicas for the Chamber of Horrors in their associated waxworks.

But equally, while researching my recent book on colonial crime writer Mary Fortune, I encountered individuals living in 19th-century Melbourne who seem startlingly modern. A wealthy teenage girl who dressed in drag for months as The Boy-Girl, likely as a protest. A radical journalist and sometime criminal who published a lurid true-crime newspaper. And a Black author and activist who advocated for workers’ rights, the unemployed and men of colour.

This trio did not fit the mould – nor do they fit our preconceived views of what colonial Australians were like. They were ratbags: a term extremely expressive of the national character, then and now. They had the strength of character to be different, subversive, even to protest publicly. They did what they wanted, against constraints – and they deserved better than to be forgotten.

The Boy-Girl

Let us start with dress. A man wearing a dress would not be immediately arrested these days. No one would cite the Biblical injunction against cross-dressing, Deuteronomy, at them. But in 1857, French artist Rosa Bonheur had to get permission from the Prefect of Police to wear pants, for reasons of “health”.

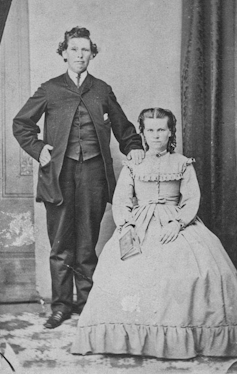

Family photographs from the Victorian era depict rigid gender roles in dress, with father in trousers, tailcoat and top hat, mother in crinoline and bonnet, surrounded by their many offspring. Yet those roles could be bent, or blurred. Look more closely at the youngest children in these photographs. Small boys wore frocks and their hair long, until “breeched”, put into pants. Even the macho Ernest Hemingway once wore frills and furbelows, most cutely.

In 1875, Melbourne’s Block, the promenade space of the fashionable wealthy, was the site for a challenging display: the Boy-Girl. Here, notions of gender were confounded by an individual dressed as female from the waist down, but male from the waist up. As a letter to the Herald noted:

Sir,– A most distressing sight is to be seen every evening on our principal streets, viz., a poor boy evidently from want of means going about in petticoats, perhaps his mother or sister’s. I would gladly subscribe my mite towards providing him with suitable nether habiliments, and I trust the matter will be taken up by our charitable public. Yours,

“PANTALOON”

21st September. P.S. – Since writing the above a friend has told me the object of my pity is a girl – this must be a joke.

While this letter may have been tongue in cheek, it expressed the general puzzlement. The act was clearly performative, and it happened daily, from 4-5pm. Above the conventional woman’s skirt was a man’s jacket, tie, hat, starched collar and even monocle. The hair was cropped: something prescribed for women suffering fever, but not flaunted in the street. One observer noted slangy speech, loud laughter, a bold gaze – all unwomanly behaviour.

At the time the very act of being a woman in public, rather than the idealised domestic Angel in the House, was considered daring. Walking the streets was a euphemism for prostitution, as with the French “faire le trottoir”.

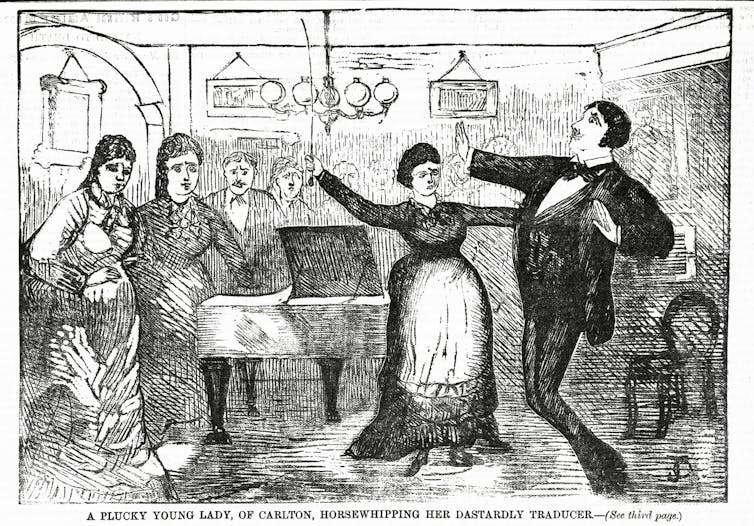

The Boy-Girl proved a sensation in the colonial media. No known photographs survive, but there are Punch engravings. The first, from winter 1875, has the heading IN DRAG, and shows an Irish cop protesting: “If yez ain’t a man in female’s clothes, yez a male in man’s clothes …”

A man in a woman’s dress faced being jailed in Pentridge. Gordon Lawrence, who co-blackmailed bestselling author Fergus Hume for the then-crime of homosexuality, was arrested in 1888 for “soliciting”, in a bustle outside the Melbourne Exhibition Building. He was sentenced to six months in prison, for vagrancy and “insulting behaviour”, a catch-all charge covering obscenity to prostitution.

In 1879, servant, blacksmith and gold miner Edward De Lacy Evans achieved worldwide fame when revealed to be a cross-dressing woman during their stay in an insane asylum.

The right to be sinful?

In the Boy-Girl’s case, any arrest would have been a major problem. The Boy-Girl’s father was one of the richest men in Melbourne. Kate Johnson, then 17, had been born in Mount Gambier, South Australia, to Archibald and Mary Johnson. Archibald, a Scots Presbyterian, had worked his way up from station overseer to pastoral magnate, with sufficient wealth to buy Stonnington, a major mansion, in his retirement. Of his large family, Kate was his favourite. She would promenade as the Boy-Girl for months.

Her act was primarily visual and she never commented on it publicly. An “interview” with Punch appeared under the heading “Practical Papers on Vice”. Though written with irony, it claimed the Boy-Girl wanted equality of the sexes and rights for women – including the right to be sinful. The journalist concluded the Boy-Girl would lead to a future race of Australian hermaphrodites.

Others termed her “eccentric”, or claimed the stunt was to win a lucrative bet, though the Boy-Girl did not want for money. When she stopped, to grow her hair again and dress conventionally, it was to study music and drama, at professional level. In 1877, she took to the stage, a natural progression given that theatre was a liminal space regarding gender roles. Pantomime featured cross-dressers, with the Principal Boy (an actress) and the Widow Twankey, a caricature of femininity even more grotesque than Edna Everage.

It was an unusual move for a rich young lady, since actresses were regarded as being little less than whores, however glamorous. One journalist deplored her move, saying “we fathers and brothers” only wished to keep womenfolk pure, and “out of the sight of impurity”. Johnson played Kate in The Taming of the Shrew, to a packed house but poor notices. More successful were piano performances, where she showed both skill and brio.

What might have been a brilliant career came to a premature halt in February 1878. Kate died at Stonnington, of typhoid fever – the mansion had bad drains. Crowds lined the streets to watch her funeral cortege. Even journalists who had mocked her expressed sorrow.

Her grieving parents planned a memorial, of Carrara marble, 14 feet high, in Melbourne General Cemetery, with a portrait of Kate, and of her mother, weeping at the base. It never eventuated. Archibald died in 1881, with his will bitterly contested. A marble bust of Kate was completed. Once in the Victorian National Galley, its location is now unknown.\

A ratbag radical journalist

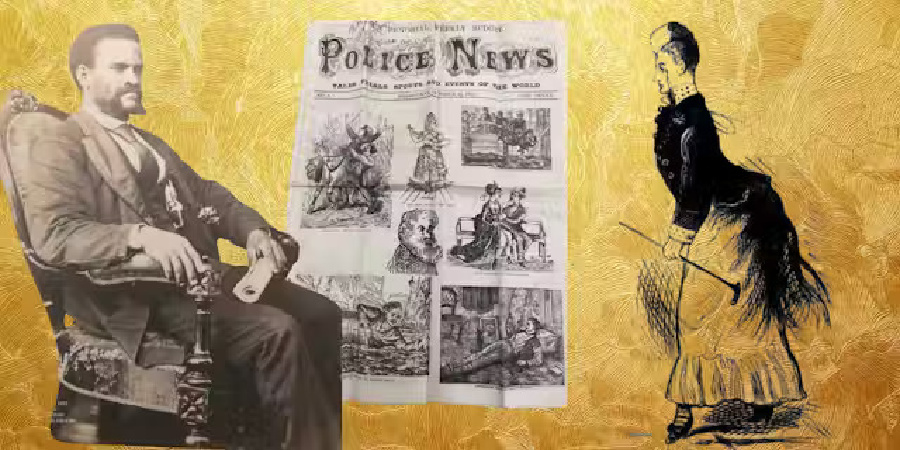

Popular commentary on the Boy-Girl included an 1877 poem, printed in the sensational weekly Police News. Its editor, Richard Egan-Lee (1809-1879), was also a noted ratbag. During a busy and disreputable life, he was a printer, publisher, inventor and radical journalist. He had at least 12 children with four wives, likely involving bigamy. Egan-Lee was one of only two people sued successfully by Charles Dickens, for pirating A Christmas Carol. Insolvencies following, he emigrated in 1863 to Melbourne.

Typically, Victorians were fascinated by true crime, but Lee had personal experience. In 1866 he was sent to jail for 12 months, for stealing type. He emerged to work editorially on the popular fiction magazine the Australian Journal, but anonymously. His eight-year tenure overlapped with Marcus Clarke. One of Lee’s descendants recalled that Clarke wrote For the Term of His Natural Life in Lee’s office, which sounds inconvenient.

Observing the success of the US Police News, featuring sensational true crime, Lee produced his own Australian version. It featured not only crime but radical politics. He declared its mission as: “to drag forth into the light of day, more shams, frauds, and humbugs, than all the other papers put together […] ever since Victoria was a colony”. He added that Victorian society was “composed of the rankest duffers and the most consummate veneered hypocrites that can be found in any country”. From the law and legislature, to the police, press and the pulpit, “all is a mass of make-believe and mockery”.

His Police News was wildly popular. Lee sold 17,000 copies weekly: a huge circulation for the colonies. Part of the success was lurid illustrations, sourced from the public: Lee would ask crime witnesses to send in sketches, which he then had engraved in an innovative process he termed zincotype. The Age deplored his “literary garbage”, but he outsold it.

Small wonder he got sued, for obscenity, though the offending illustration merely showed a man and women drinking in a bar; he was also sued for libel. The magazine ran on a shoestring and indignation. It also displayed a fascination with strong women: revenging themselves on seducers, repelling burglars, even murdering.

Lee seems a proto-feminist. He devoted an editorial to “man’s inhumanity to women”. He was also a sympathetic editor to crime writer and journalist Mary Fortune, unlike the misogynistic Clarke.

Lee died of typhoid fever (like Kate Johnson), in 1879. Few copies of his magazine survive, but the unique art project of his Police News was the subject of an exhibition by noted artist Elizabeth Gertsakis in 2018.

A Jamaican Black activist

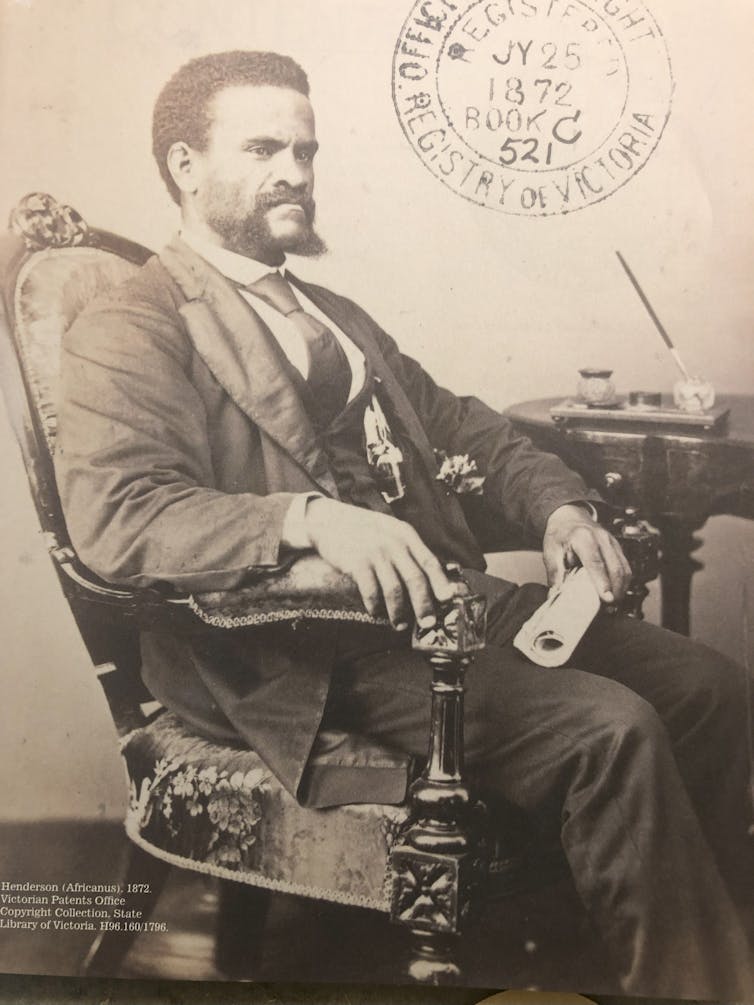

Our last ratbag, like Kate Johnson, appeared in Punch, where he was rendered with stereotypical racism, talking like Uncle Tom. His photograph shows formidable attitude, not least as a man of letters.

Daniel Henderson was an Afro-Jamaican author and activist. A journalist termed him “Henderson Africanus”, after the Roman general Scipio Africanus. Henderson proceeded to own the nickname, proudly adopting it as “an African Political General”.

Like the Boy-Girl, he made a public display, a celebrity selling newspapers in a huge white hat, but also giving speeches and campaigning via letters. He was politically active, a proud and loud Black man.

Daniel Ross Henderson was born in Kingston, Jamaica, son of Thomas, a cabinet-maker, and his wife Elizabeth. The family were politically engaged. Daniel was named for Daniel O’Connell, former Lord Mayor of Dublin, an activist for emancipation as well as Irish rights.

The formidable Elizabeth legally and vigorously fought a claim against her freedom, and favoured education for her son. Henderson would find advancement and mobility in the British Navy, which took men upon their worth, not race. That led him to emigrate to Australia. In 1880, he married a white woman, Aphra Lightbourne, of military background.

As a child, he had read the political section of newspapers aloud to his father and workmen. Now, he sold newspapers in Exhibition Street. The proximity to Parliament House was no accident. In 1868, government supply was blocked by the Victorian Legislative Council. Henderson responded with a 24-page pamphlet, Our Imbroglio: (The Crisis) and Our Way Out of It, which closely examined constitutional law. Ten years later, a similar crisis sent political leaders Sir Grahame Berry and Charles Pearson to appeal to London, personally.

The received wisdom is it was an Opposition joke that Henderson be proposed to accompany them. The magazine Table Talk, which had the best gossip, said Punch cartoonist Tom Carrington was behind it. Carrington knew Henderson was good copy. He denigrated him racially and politically in Punch, a Tory publication.

Truth was, Henderson had already argued the case articulately and well. Newspapers and the Bulletin would note Henderson was “really one of the founders of the great liberal party” (Premier Graham Berry’s party and in those days, radicals). He was a presence, a public intellectual, who just happened to be also a Black man. The degree of vilification he faced shows how much he challenged notions of nineteenth-century race. Although Henderson tried standing for parliament several times in the 1880s and 1890s, he was never pre-selected.

Instead, he devoted time to causes such as worker’s rights, the unemployed and men of colour in serious trouble with the law. The Public Record Office preserves many of his distinctive purple-inked letters, including to the police commissioner. One prompted an formal investigation into the case of Antoine Bollars, his lodger, who (with Gordon Lawrence) had blackmailed Fergus Hume. Bollars, also Afro-Jamaican, had been convicted of a homosexual indecent assault, which occurred under Henderson’s roof. It was an unspeakable crime, but Henderson had the courage to intervene.

He was cranky, a show-off, but with the wit and force of character to defy the contemporary strictures on Black people. When he died, of peritonitis, even Punch had to admit he was “a well-meaning and good fellow”.

Bloody minded, showy and bold

A teenage girl who pushed the public limits regarding accepted notions of gender. A radical journalist and inventor who crusaded against the blackguards of his colony in one of its most successful magazines. A politically active Black public intellectual.

They captured public attention, but after their deaths they were soon forgotten.

That they existed at all in their conservative era seems extraordinary – but that they persisted against the formidable opposition is a lesson in personal courage. It is also a lesson in the virtues of ratbaggery.

Let us celebrate those who go against the grain, for they have often have the uncomfortable tendency to be right. And we can learn a good deal from them that can be applied to our troubled times: not least the virtues of political performance art, and of being bloody minded, showy and bold.

Lucy Sussex, Honorary Associate, Humanities and Social Science, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.