Republished from the website: themusic.com.au

Author’s website: http://www.jessicabellauthor.com/

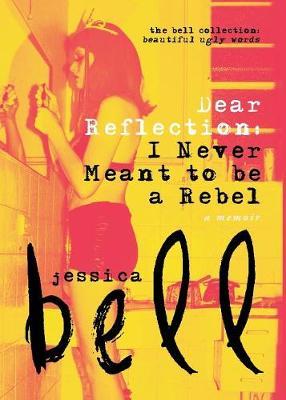

Melbourne-born, Athens-based poet, author, publisher, designer, teacher and musician Jessica Bellreleases her insightful, incredibly candid memoir, Dear Reflection: I Never Meant To Be A Rebel.

The book is a firsthand recount of her turbulent youth and early adulthood as the child of Erika Bach and Demetri Vlass, founders of seminal Melburnian indie bands Ape The Cry and Hard Candy. Though loving, encouraging parents, Bach and Vlass battled their own demons over the years, the former managing a back problem that “became a nightmare of pill popping, alcohol abuse and anxiety attacks”, and the latter “retreating into silence for fear of triggering Erika’s drug-induced psychosis”.

To cope, Bell “turned inwards, to her own reflection” — a journey that ultimately took her through the travails of depression and self-destruction, “to escape the madness at home”.

The Music is proud to host this exclusive book excerpt, which picks up the story ahead of Bell’s 15th birthday, just over 20 years ago.

Back in Australia, in early 1996, before my fifteenth birthday, my parents invited friends over for a Saturday night drink — Melanie, Mum’s back-up vocalist, and her new boyfriend, Sean. An Aussie-Greek eccentric called Patrick, who they’d met on Ithaca the year prior during drunken escapades, also turned up. I sat in the living room with them, assuming their drinking and smoking and chemically induced laughing was normal behaviour. I had fun watching them, being around them; it made me feel cool to have cool parents. And to top it off, their friends were like aunts and uncles to me because they treated me as one of their own. (It also helped that one day when Demetri picked me up from school, a student asked if he was the drummer of Faith No More. I said, “Yeah, he came all the way from America to pick me up.” This felt like a social leg up.)

I’m sure Mum thought she’d hidden the pot smoking from me by sending everyone into the backyard to smoke it, but I knew what it smelled like. I wasn’t stupid. After all, my high school took its nickname, Mull-cleod High, from the slang for the tobacco mix used with marijuana.

I overheard a conversation between Mum and Patrick as I approached the kitchen to grab myself some lemon squash. The door was open an inch, and I peeked through the gap. Patrick was begging her for a Valium, wiggling his lanky limbs around like they were about to fall off. His dead-straight shoulder-length hair was hooked behind his ears, accentuating his Mediterranean nose. “Come on, Erika,” I heard him say, among other things, in his nasally but charming voice, in an attempt to persuade her to give him one. I don’t know if she was reluctant to give him one because she was running out, or whether she thought it would do him harm. In the end she gave him one. It was to relieve his rib and back pain — which, I seem to recall, turned out to be a hairline fracture in his ribs from a drunken summer fall on Ithaca.

As the night went on, and Mum began to sway from side to side every time she stood up, she disappeared for longer than it would take to top her glass up with vodka.

“Where’s Mum?” I asked Patrick.

“Uh … she’ll be back in a minute.”

“But where is she?”

“You don’t want to go out there,” he said with a chuckle. I made my way through the kitchen, the glass extension I had now shaken my fear of, and into the backyard. Mum hung from her hips over one of the supporting bars of my now unused orange and lime-green swing set. Her body hung limp in the shape of the Greek letter Λ, the ends of her now shoulder-length red hair stroking her chunky vomit in the grass with each heave.

I walked over to her, rubbed her back, and tried to get her to stand up so I could help her to bed.

“Don’t tell Mum,” she said in the voice of a child. “I’m not allowed to drink.”

I stayed out there for a few minutes, holding her hair out of her face, as she vomited. Though I wanted to care for her, I was really tired and needed to go to bed. I had homework to do the next day.

My parents’ friends passed through the backyard on their way out and wished us good luck. Demetri helped me get Mum to bed. We guided her in silence. Demetri was either too out of it to say anything coherent, or simply being his usual silent self. I didn’t know what to say, but not out of anger or disappointment. I had disassociated myself from the situation. I made the necessary moves as if being controlled by a remote, even though I had never done this before. My ability to block out emotionally challenging experiences had switched itself on without any conscious provocation.

Demetri and I sat Mum on the edge of her bed, and I stood up, assuming this was all I was required to do.

“Don’t leave me,” Mum pulled on my arm. “Please stay.”

I glanced at Demetri.

“I’m gonna tidy up,” he said, pushing his long black curls out of his face. “Won’t be long.” He wobbled down the hallway in his bare feet, skinny black jeans, and shirt with a flamboyant green, white, and black pattern, and closed the kitchen door behind him.

I lay down next to Mum. Demetri brought a wet face cloth, a towel, a bucket to throw up in, and left them on the floor. The stench of fermented pizza and alcohol emphasized the foulness of the chunky splash as her vomit hit the bottom of the bucket. When it seemed she had nothing left in her stomach but bile, she held her nostrils closed and tried to breathe through them.

“I can’t breathe,” she said, panic creeping into her nasally voice. “What’s wrong with me? I can’t breathe.”

“Stop holding your nose and you’ll be able to breathe,” I said.

She shook her head from side to side, still pinching her nose closed. “I can’t breathe. Help. I can’t breathe.”

“Breathe through your mouth,” I said. If she wasn’t going to stop holding her nose closed, it seemed like a logical thing to tell her to do.

She shook her head again. “Nope. It’s not natural to breathe through your mouth. I need to breathe through my nose.”

“Then let go of your nose, Mum.” I rested my head on Demetri’s pillow. It smelt of Sunsilk conditioner and methylated spirits.

“Don’t tell my mum, okay?” she said again in a sleepier tone. “I’ll get punished.”

“I won’t.” My head sank farther and farther into Demetri’s pillow as I focussed on the sound of clinking dishes coming from the kitchen.

Mum released her nose and took a long deep breath through her nostrils.

“Better?” I said.

She nodded and smiled — “I still can’t breathe.” — and held her hand to her head. “Don’t tell my mum, okay?”

“I promise.” I rolled my eyes. “I won’t tell your mum.”

For a moment I thought how cool this story was going to sound when I retold it at school on Monday. I pictured myself in my mother’s shoes, Tim or Nelly nursing me like I nursed her. I imagined the stories that would spread about me, how I might actually be considered cool, and maybe a rebel. Maybe if I got drunk in front of my peers, I would become a ‘real’ teenager, and more people would want to hang out with me.

I decided. I would get drunk at the next party I was invited to.

I sat up to check if Mum was falling asleep. Her eyes were closed and her chest rose and fell at a normal pace. Demetri returned. We exchanged glances and I slinked off the bed. We hugged each other goodnight and I tip-toed to my bedroom.

Being alone in my bed had never felt so good.

I don’t know why she told me she couldn’t breathe after she clearly could. Maybe it was code for something else. Maybe she couldn’t breathe in this world.

Maybe the world was suffocating her, as I felt it was suffocating me.

Friday afternoon, the following week, I sat in the middle of my bedroom floor listening to the movements being made in the house.

On the right, towards the music room …

… the clicking of guitar leads as they unwound

… the crack of a lead being plugged into an amplifier

… the one tzew tzew of Demetri’s voice testing the volume of the microphone, the tuning of his Les Paul, the accidental feedback, Mum clearing her throat and muttering, “Is the tape in?”

Then the sound I was waiting for: the door to the music room clacking shut.

I rummaged through my school bag and pulled out the empty water bottle I’d been saving, inched open my bedroom door, tip-toed into the living room and closed the door behind me.

I twisted the cap off my water bottle and poured in an inch of Stolichnaya, an inch of Cointreau, an inch of Bombay Sapphire Gin, an inch of Ouzo, and an inch of Drambuie.

When Demetri dropped me off at the party, he told me to be good. He always said ‘be good’ like he didn’t really know what he was asking. It was just what parents were supposed to say, right?

Be good.

What does that mean exactly?

I walked through the long corridor of Nelly’s incense infused house and into her backyard, pulled out my concoction and took a big swig. I hid the bottle back in my bag as I didn’t want people asking what it was. The sting of the potent spirits didn’t make me wince, instead it warmed my chest with an intense feeling of release.

Tim offered me a cigarette, flicking his dreadlocks to one side of his face. I glanced at the knee-wide rips in his light blue jeans, hesitating before taking the cigarette.

Tim chuckled. “You smoke?”

I didn’t. It was my first one.

I shrugged. “Only at parties.”

“Cool,” Tim said, jolting. Nelly had pushed a stubbie into his neck with her blue-black fingers — she’d dyed her hair again. She poked him in the ribs and he took the beer.

I put the cigarette in the left corner of my lips.

“Nell, you gotta light?”

“Sure.” She pulled a box of Red Head matches out of her back pocket. “Wanna beer too?”

I nodded with a half smile, trying to act cool, as I struck a match against the box and lit the cigarette as Nelly went back inside.

On the first drag I coughed and spluttered, but managed to control it and hide it enough for it to look like it wasn’t the cigarette’s doing. So I thought. A few kids I didn’t know turned around and looked at me. One very tall girl, with a masculine build, smirked. Our glances collided momentarily before I flicked my head in the opposite direction. My stomach turned with embarrassment as I realized I was sitting on the edge of Nelly’s slightly raised garden bed all on my own. I had to make up for this minor deflation in my yet-to-be-established reputation.

“All good?” Nelly said, approaching with a VB stubbie. I nodded. She gave me two thumbs up and walked over to Tim who was now on the other side of the yard, laughing and drinking with a bunch of blokes who were talking about some neighbour with big white tits.

I swigged my beer intermittently, staring at the tufts of trampled brown grass that grew through the cracks in the ground. Cigarette butts and pieces of broken brown glass adorned the perimeter of a harassed tree whose roots tried to break free through the concrete.

I held each drag of the cigarette in my mouth, without inhaling it. I’d tilt my head to the right and slightly upward when I exhaled. That was how the other girls were doing it.

I got tipsy pretty fast and remember thinking I could do anything — that I was invincible. No wonder my mother told me she used to drink a whole bottle of vodka before a gig.

It really did make you feel like a rock star.

Rage Against the Machine’s ‘Killing in the Name’ blared through Nelly’s back door.

I nodded my head to the strict heavy beat, the words Fuck you I won’t do what you tell me, etching into my mind.

Be good.

I was good. I had never felt more alive.