By David Haworth, Monash University

The black swan is an Australian icon. The official emblem of Western Australia, depicted in the state flag and coat-of-arms, it decorates several public buildings. The bird is also the namesake for Perth’s Swan River, where the British established the Swan River Colony in 1829.

The swan’s likeness has featured on stamps, sporting team uniforms, and in the logo for Swan Brewery, built on the sacred Noongar site of Goonininup on the banks of the Swan.

But this post-colonial history hides a much older and broader story. Not only is the black swan important for many Aboriginal people, it was also a potent symbol within the European imagination — 1500 years before Europeans even knew it existed.

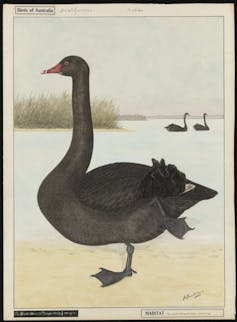

Native to Australia, the black swan or Cygnus atratus can be found across the mainland, except for Cape York Peninsula. Populations have also been introduced to New Zealand, Japan, China, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Right now, the breeding season of the black swan is in full swing across southern Australia, having recently ended in the north. In waterways and wetlands, people are seeing pairs of swans — a quarter of which are same-sex — tending carefully to their cygnets, seeing off potential threats with elaborate triumph ceremonies, or gliding elegantly across the water, black feathers gleaming in the winter sun.

Yet once upon a time in a land far away, such birds were described as rare or even imaginary.

The impossible black swan

In the first century CE, Roman satirist Juvenal referred to a good wife as a “rare bird in the earth, and very like a black swan”.

Casual misogyny aside, this is an example of adynaton, a figure of speech for something absurd or preposterous — like pigs flying, or getting blood from a stone.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: Juvenal, the true satirist of Rome

Over the centuries, versions of the phrases “black swan” and “rare bird” became common in several European languages, describing something that defied belief. The expressions made sense because Europeans assumed, based on their observations, that all swans were white.

Around the same time that Juvenal coined these phrases, Ptolemy devised a map of the world that included an unknown southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita. Many believed this distant southland was populated with monsters and fabulous races, like the Antipodes, imagined by Cicero as “men which have their feet planted right opposite to yours”.

In a quirk of history, both the impossible black swan and the hypothetical southland were indeed real. Even more unbelievably, they would be found at the same geographic coordinates.

Once they were white

Black swans are significant totems for many Aboriginal people and incorporated within songlines and constellations (where they are called Gnibi, Ginibi, or Gineevee).

Yet the Noongar people in WA, and the Yuin and Euahlayi in New South Wales, tell ancestral stories about white swans, which had most of their feathers torn out by eagles.

In the Noongar story Maali, the swan, is proud and boastful of its beauty, and has its white feathers ripped out by Waalitj, the eagle, as punishment. In the Yuin story the swan, Guunyu, humble and quiet, is attacked because the other birds are jealous of his beauty.

And in the Euahlayi story, two brothers are transformed into swans, or Byahmul, as part of a robbery. Later they are attacked by eagles as an act of revenge.

In each story, after the swans have their white plumage torn out, crows release a cascade of feathers, turning the swans black, except for their white wing tips. Their red beak still shows blood from the attack.

These stories are keenly observant of, and offer an explanation for, the black swan’s colouration. They acknowledge the possibility swans could be white — even though it’s unlikely First Nations people observed white swans in their surroundings prior to British settlement.

This contrasts starkly with the European assumption that, having never seen a black swan, they couldn’t possibly exist.

Read more: 6,000 years of climate history: an ancient lake in the Murray-Darling has yielded its secrets

From myth to wonder

European assumptions were destined to shatter once Dutch ships began visiting Australia’s western coastline in the 1600s. Seeing the mythical black swan in the flesh must have been like seeing a unicorn emerge from the shadows of the forest.

In 1636, Dutch mariner Antonie Caen observed black birds “as large as swans” at sea off Bernier Island — probably the first recorded European sighting.

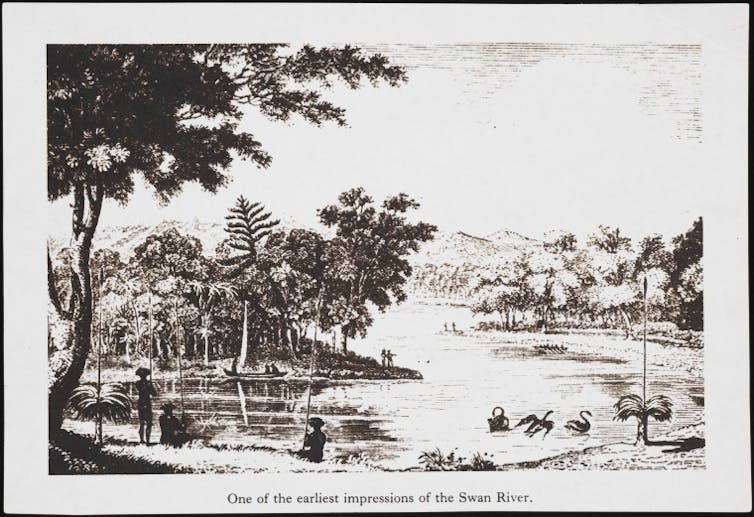

In 1697, Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition to the west coast sighted many swans on what they dubbed Swarte Swaane Drift or Black Swan River. Noongar people know this river as Derbarl Yerrigan. If de Vlamingh was amazed at the sight of black swans, he did not record it, simply noting, “They are quite black”. Three swans were captured and taken to Batavia (Jakarta), but died before they could be brought to Europe.

Reports of the black swan made it back to the Netherlands and then to England, but it took another century for its mythical status to dissipate completely.

English ornithologist John Latham gave the black swan its first scientific name, Anas atrata, in 1790. Yet knowledge of its existence was still not widespread.

In 1792, the botanist on Bruni d’Entrecasteaux’s expedition, Jacques Labillardiere, made note of black swans at Recherche Bay in Tasmania, apparently unaware they were already known to Europeans.

In 1804, Nicolas Baudin’s expedition brought the first living specimens to Europe. These became part of the Empress Josephine Bonaparte’s garden menagerie at the Château de Malmaison.

The black swan had migrated from myth to the far edge of reality, joining the kangaroo and the platypus as awe-inspiring wonders from the distant, topsy-turvy southland — real, but only just.

Good versus evil

Black swans never established large populations in the wild after being brought to Europe. It’s speculated this is because black animals were considered bad omens, in league with witches and devils, and often driven away or killed.

Beliefs like these reflect the ancient assumption, found everywhere from the Dead Sea Scrolls to Star Wars, that darkness and the colour black represent evil and corruption, and that light and the colour white represent goodness and purity.

Frantz Fanon once argued that “the colonial world is a Manichean world”, in which light and dark, white and black, and good and evil are starkly divided. These divisions have been deeply implicated in the histories of colonialism and racism — often with devastating consequences.

Two swans, one dancer

The symbolic contrast of light and dark features heavily in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s most famous ballet, Swan Lake. Prince Siegfried falls in love with Odette, the innocent and virtuous white swan. But he is tricked into promising himself to her double, the seductive and malevolent Odile.

The ballet’s story was inspired by a long tradition of European fairy tales depicting Swan Maidens, but Tchaikovsky was also reportedly inspired by the life of King Ludwig II of Bavaria, known as the Swan King. Both Ludwig II and Tchaikovsky were caught between the societal pressure to marry and their own same-sex desires.

The roles of Odette and Odile are often played by the same ballerina, a tradition that started in 1895, two years after Tchaikovsky’s death. But it was not until 1941 that Odile was first depicted wearing black, and afterwards became known as the black swan.

Swan Lake suggests a Manichean worldview in which good and evil are polar opposites, as far away from each other as Europe is from the Antipodes. By having the same ballerina portray both roles, the ballet also suggests the world is not so simple — things can be black or white, or both at once.

False black swans

For 1500 years, Europeans had been spectacularly wrong about the black swan. Once its existence was accepted, its transmogrification from myth to reality became a metaphor within the philosophy of science. The black swan had shown the difficulty of making broad claims based on observable evidence.

Austrian philosopher Karl Popper used the black swan in 1959 to illustrate the difference between science that can be verified versus science that can be falsified.

To verify that all swans are white is practically impossible, because that would require assessing all swans — yet a single black swan can disprove the theory. In 2007, essayist and mathematic statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb argued organisations and individuals should be robust enough to cope with “black swan events”: consequential but unexpected moments in history.

Read more: Friday essay: the long history of warrior turtles, from ancient myth to warships to teenage mutants

The white black swan

This Australian winter, those enjoying the sight of black swans and their cygnets might assume, based on observable evidence, that all Australian native swans are black. But as black swans have shown, and as Taleb argued, we should expect the unexpected.

Last month, some four centuries after Europeans were awe-struck by the sight of black swans on our waters, Tasmanian fisherman Jake Hume rescued a white-plumaged black swan, the only one known to exist.

The swan is not an albino, because it still has pigmentation around its beak and eye. Its white feathers are the expression of a rare genetic mutation. First sighted in the area in 2007, the bird was found riddled with shotgun pellets. It is recovering in Bonorong Wildlife Sanctuary until ready to be released.

Simultaneously a black swan, a white swan, and a metaphor, this assumption-shattering “rare bird” captures the complex cultural history surrounding this species.

David Haworth, Senior Research Officer, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.