The choreography of the whole event is unmistakable as national performance. Even the birdlife at the foot of Mount Ainslie seems to recognise it has a role to play with its singing and screeching and laughing – instantly recognisable as an Australian soundscape – alongside the speechmakers, catafalque party and bugling of the Last Post.

Read more:

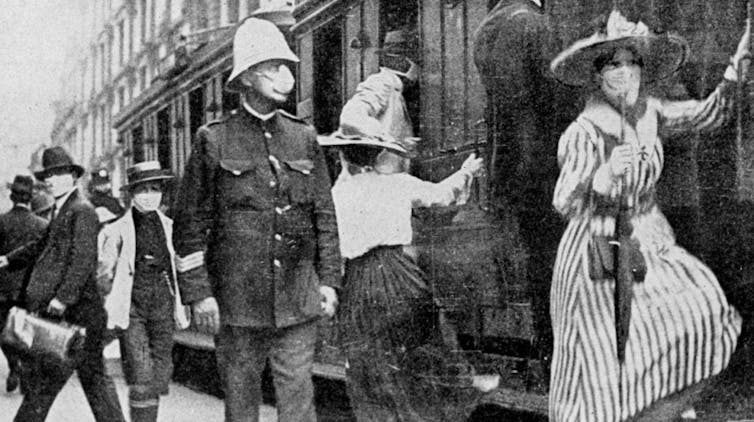

How Australia’s response to the Spanish flu of 1919 sounds warnings on dealing with coronavirus

This year, thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, it will be different. The dawn service will be held without members of the public, but will be televised on the ABC and streamed online. There will be no local marches.

The Returned and Services League (RSL) has encouraged people to film themselves reciting the ode in their homes and post it online. The RSL is partnering with News Corp in Light Up The Dawn, asking Australians to step into their driveways to observe a minute’s silence, possibly carrying a candle or using mobile phones for illumination. They have even created a virtual candle you can download to your phone.

We can be sure the novelty of the 2020 Anzac Day commemoration will attract plenty of media attention. The Australian media have a ready-made, multipurpose rhetoric that is easily adapted to whatever novelty – minor or otherwise – each year’s Anzac season brings with it. This year will be no exception.

We can expect to read and hear of Australians in these troubled times expressing mateship, of children in pyjamas and dressing gowns showing the young are connecting more and more with Anzac each year, that coronavirus has not dampened the Anzac spirit of the nation – and so on. We will learn of the doughty Australian suburbanites who weren’t going to let a mere global pandemic get in the way of their appreciation of those who defend their freedoms. Our health workers will be seen as displaying the self-sacrifice and heroism of Anzac, born all those years ago on the shores of Gallipoli.

Anzac 2020 will be less novel than it is presented. In the enforced private nature of Anzac commemoration in 2020, we are being returned to some of the earliest themes in Anzac commemoration.

While the day has had its elements of public ritual since 1916, much early Anzac Day commemoration was private rather than public, sometimes conducted at the gravesides of Australian soldiers buried in cemeteries in Britain and Australia. Women were prominent in these efforts, honouring the memories of men they might or might not have known by placing flowers on their tombs.

Parramatta Heritage Centre

There are other echoes of the past. Anzac Day in 1919 was also disrupted by a major crisis in public health. In New South Wales, where the rate of infection from Spanish influenza was high and the number of deaths – approaching 1,000 by Anzac Day – was alarming, the government had banned public meetings.

The government called off the march until May 22. When that happened, it was a fiasco. Rain prompted organisers to decide against marching all the way to Sydney’s Domain, and soldiers and sailors who had come from Central Railway Station instead slipped straight into the service in the Town Hall. Unfortunately, no one remembered to tell the thousands of people lining the streets to watch.

On Anzac Day itself, there had still been activity – more than we’ll see this year. The Centre for Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers appealed to the parents of the city’s children – home for their Easter break – to take their Shakespeare down from the shelf and read their children Henry V’s speech to his troops before Agincourt.

Gallipoli might have made the nation, but Australians still looked for inspiration to a much longer British history stretching back through Mafeking, Rorke’s Drift, Balaclava, Waterloo and Trafalgar – and even further to that “band of brothers” who made short work of the French on St Crispin’s Day, 1415.

The Centre of Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers held a service in the Domain. “Womenfolk, many of them in mourning, preponderated”, the Sydney Morning Herald reported, and most were wearing masks. The location of this service was pointed: it was at Woolloomooloo Bay, where so many soldiers had embarked for the war.

Outside Sydney, there was also some disruption. “The Approach of Anzac Day this year was overlooked locally,” explained a local newspaper at Dorigo in northern New South Wales. “Owing to the presence of the influenza epidemic, the thoughts of the people seem to have been turned away from other things.” But there were Anzac Day activities; a surprising number, actually.

Anzac Day was commemorated at Lismore, notwithstanding that the town had seen several serious cases of influenza and, in the week before Anzac Day, the deaths of two men. At Grafton, thousands enjoyed a soldiers’ carnival. And in the other states, there were few signs of difficulty:

Adelaide was gay with flags from end to end, and the trains and tramcars brought thousands of people into the central city to view the procession of soldiers.

In Brisbane, despite heavy rain, the route of a march of soldiers and returned men “was lined with thousands of people”.

Australia Post

A subdued Anzac Day in Perth was attributed not to the influenza but to the authorities’ hope that the proclamation of peace in Europe would be timed so that the two “celebrations” might merge.

In 1919, as soldiers returned to Australia on ships and often went into quarantine, the nature of Anzac Day commemoration remained fluid. It was still not a public holiday, and the Anzac Day march had not yet become an essential or permanent fixture of the city commemorations. Melbourne had no march on April 25 1919, but then it didn’t have a march on most other Anzac Days in these early years, either.

Some will be disappointed there will be no marches and other public gatherings this year. But Anzac Day 2020 is less likely to be recalled as an absence than as yet another way in which Australians adapted their national life to the challenges of the greatest public health crisis for a century.

Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

November 11, 2021 at 4:06 am

I really do love your work now after this. I just hope you will give us more stuff like this in the future… Regards office.com/setup